The liberation of Mme de Tencin. From convent to court, from bank to boudoir, she was always prone to argue. It was the end of the Louis XIV reign, a hey-day of cynical license that characterized the Regency period that followed, a time to make up the arrears of pleasure that Mme Tencin thought her due, as well as the pursuit of money….

Lord Chesterfield:'”She (Madame de Tencin) had been a nun, and quitted her convent, and to the end of her life was engaged in all sorts of intrigues, gallant, political, and interested. She was suspected of having robbed and murdered one of her lovers, and was saved from prosecution by the interest of another of them, Lord Harrington.

” The author, D’Alembert, was her natural son, and Monsieur de Pontdeyvelt (Pont de Veyle) her nephew, who fathered, as it

was supposed, her two famous novels, the ‘Comte de Cominges,’ and the ‘Siege of Calais.’ The celebrated Madame de Geoffrin was one of her pupils.

—Madame de Tencin resided at Paris, and was sister of the famous

Cardinal de Tencin, and noted both for wit and intrigue. She was the

patroness of men of letters; Fontenelle and Montesquieu were among

her friends.

—Chesterfield

…Now a very annoying thing happened. Mme de Tencin had a favorite, almost official, lover, La Fresnais, tall and handsome, a mighty man with the ladies, and a fool. He was associated with his mistress in financial deals beyond his comprehension and ours, but the outcome was that she seemed to have all the money and he had none. He became convinced that she meant to murder him. He made a will accusing her of every misdemeanor, sat down on a sofa in her boudoir, and in a burst of ungallantry, shot himself in the heart. A servant ran to find La Fresnais dead and his clothing ablaze. The sofa was ruined.

Mme de Tencin was grilled by the police and lodged in the Bastille. By xhance, Voltaire occupied an adjoining cell. – ” Only a wall separated us,” he wrote, “but we did not, like Pyramus and Thisbe, kiss through a gap in the wall.”- Mme de Tencin was soon released, cleared of all imputations against he behavior and character.

This was in 1726. She was now forty-four, in poor health, getting very fat. She was bored with love, but her ambitions remained as lively as ever. She intrigued tirelessly to promote her brother’s advancement. He became successfully cardinal, French charge d’affaires at Rome, archbishop of Lyon, and minister of state. One could hardly rise higher on this earth, except to be monarch or pope. But what he chiefly desired was to be let alone.

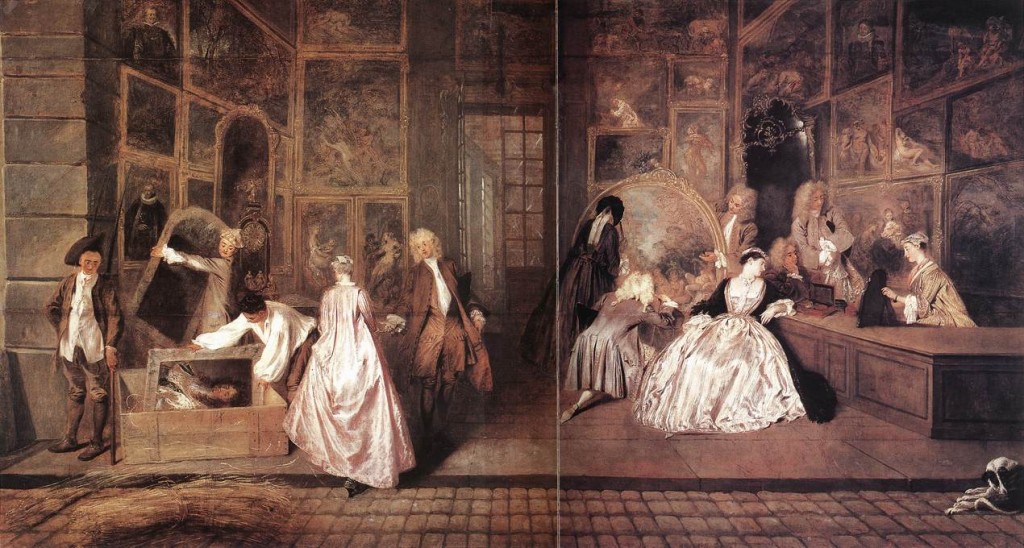

Meanwhile, Alexandrine Tencin was busy with her salon. Established in her comfortable apartment near the Louvre, it was known as “The Kingdom of the rue St-Honore.” There, every Tuesday, the wisest and wittiest of Paris gathered; the favored intimates remained for dinner. Among these were many great names: aged Fontenelle, sparkling Marivaux, learned Montesquieu, brilliant Helvetius, Abbe Prevost, creator of Manon Lescaut, and- for this was the first truly cosmopolitan French salon- distinguished foreign visitors, such as Lord Chesterfield.

ADDENDUM:

Grebel:This religious culture transcends the institution. As a multifaceted entity, religion enters the vernacular and provides a sense of morality and cultural heritage indistinguishable from Enlightenment conception of values. Even those who are strongly disposed to oppose it – such as Madame de Tencin and Rahel Levin Varnhagen –themselves participate in its perpetuation. Their own, carefully crafted letters could have been revised to eliminate a sense of religious

ession, yet they nonetheless illustrate basic religion’s unconscious, pervasive power.In using her religious background as a tool for political manipulation, Madame de Tencin highlights the conscious use of religion as an antecedent to power. It is an effective tool that speaks to the levels and layers of communication between individuals. As the coronation process, dominant from around 800 CE to the Enlightenment, elucidates, religion was intrinsically tied to French identity. Focusing on the humanistic

ideals of the Enlightenment does not negate the importance that such communication continued to hold in society. The reduction of institutional religious power and the perpetuation of religious values are not ideologically opposed realities. They are mutually beneficial in progressing society past the oppression of institution through the use of structured, moral, positive intention. Such a conscious decision by a salonnière, epitome of ‘secularizing,’ philosophical ideals, cannot be taken lightly.—

COMMENTS

COMMENTS