Al this, as his critics have shown, in Pluto and Prosperina, where god is carrying off a terrified maiden, flesh yielding beneath his grasp is quintessential Bernini: highly theatrical sculpture of overstatement. Bernini’s oen grasp towards the heaven whereby the roots of heaven were made of stone. It was Counter Reformation art, and Bernini kept undisputed control over artistic life for more than half a century with it and for merited reason. He had the hand of a sculptor and the instincts of a scenic designer.

—The Cornaro Chapel, in the left transept of the Church of S. Maria della Vittoria in Rome, is the greatest single commission of the Cornaro family outside the field of architecture and one of the most inspired monuments of art history.

Cardinal Patriarch Federico Cornaro acquired the chapel rights in January 1647 and commissioned its design and execution by Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini, 1647-52. Janson in History of Art describes Bernini as “the greatest sculptor-architect of the century” and proclaims the Cornaro Chapel “his masterpiece.”

Ecstasy of S. Teresa of Avila

The centerpiece is The Ecstasy of S. Teresa di Avila, a large statue [height 3.5m] designed to be illuminated by reflected light from a hidden window. The statue depicts a remarkable mystic experience related by S. Teresa herself:

Beside me on the left appeared an angel in bodily form . . . He was not tall but short, and very beautiful; and his face was so aflame that he appeared to be one of the highest ranks of angels, who seem to be all on fire . . . In his hands I saw a great golden spear, and at the iron tip there appeared to be a point of fire. This he plunged into my heart several times so that it penetrated my entrails. When he pulled it out I felt that he took them with it, and left me utterly consumed by the great love of God. …Read More:http://www.boglewood.com/cornaro/xteresa.html

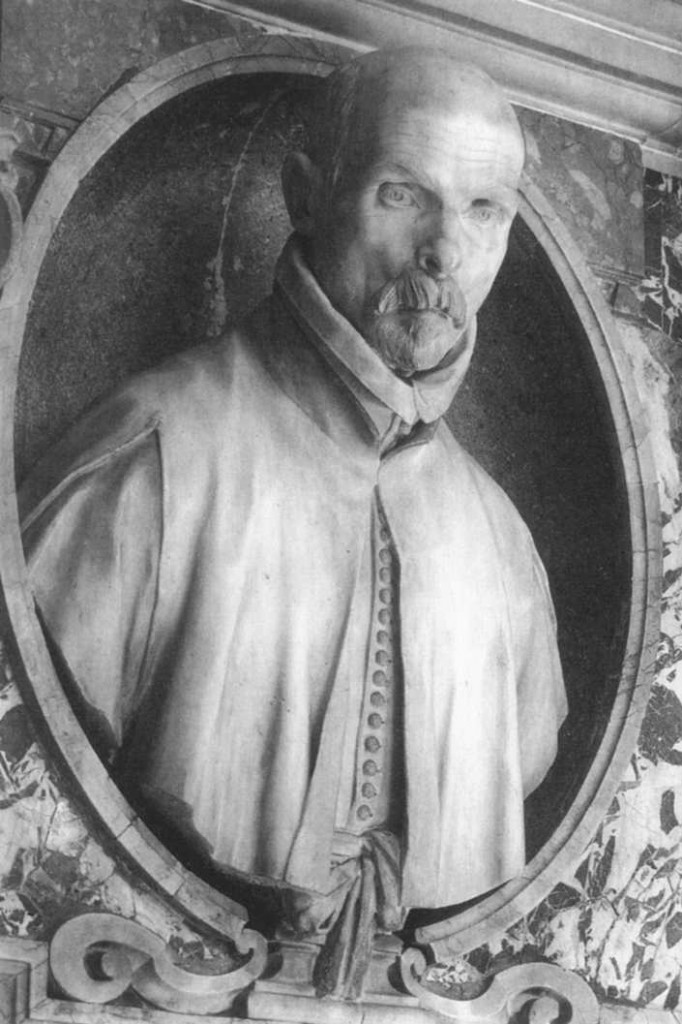

—Bust of Monsignor Pedro de Foix Montoya

c. 1621

Marble, life-size

Santa Maria di Monserrato, Rome

In his early career, Bernini often turned to portraiture to supplement his income. The portrait of Monsignor Pedro de Foix Montoya was done from life. When Cardinal Maffeo Barberini famously said that it was more lifelike than Montoya himself, he meant that the sculptor had employed the tilt of the head, the incipient smile, the half-length torso and the motif of the sash hanging over the edge of the cartouche to suggest the whole person beyond the niche. This sense of presence is further enhanced by an astonishing grasp of facial anatomy, coupled with a flair for nuances which encompasses even the bristles of Montoya’s moustache. —Read More:http://www.wga.hu/html_m/b/bernini/gianlore/sculptur/1620/montoya.html

The popes were delighted with Bernini’s work. In exchange for subsidies and favors that made him the peer of princes, he flattered them with busts while they lived and immortalized them with chapels after they were dead. He also found admirers in the College of Cardinals, source of potential popes. When he had finished the bust of the Spanish jurist, Pedro de Foix Montoya, Cardinal Barberini came to admire it and said, “It is Montoya petrified.” Montoya wandered in at precisely that moment, and Barberini said, pointing at him, “This is the portrait of Monsignor Montoya,” and than, pointing to the bust, “This is Montoya.”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS