There are few styles in art that fell so far into disrepute as the once prized academic art of the nineteenth-century. As awful as much of it was, there are still grounds for some of it to be redeemable and to be recalled from purgatory. …..

Two considerations above all else attracted buyers. One was a slick technique, which made of the painter a virtuose without any real narrative in the work; the technical level of Salon painting was quite elevated. The second was anecdotal interest. A painting first of all had to be an illustration and many painters based their success on a single anecdotal gimmick. The situation was one of a painter appealing to a new mass public on other than aesthetic grounds of which they were generally quite ignorant. An ecstatic love affair between the new affluent purchaser with mediocre taste and the technically skilled painter of mediocre conceptions. And the Salon was their trysting place.

Manet Olympia. “…They both feature courtesans gazing at, presumably, a client. “Olympia” contains some critical differences from its predecessor, though. The most obvious is in Olympia’s demeanor. She is not melting under the viewer’s gaze. She is staring them down. Manet was riffing on “Venus of Urbino” to prove a point. He wanted to show how the Venetian tradition and ideas of sexuality propagated for centuries had changed in the modern era. The most interesting difference to me is in the small details. Notice the puppy curled up on the courtesan’s bed in “Venus of Urbino.” Now look for the hunched over cat in “Olympia.” I came up with a theory about how these two animals align with the artist’s intentions. The puppy symbolizes familiarity and loyalty. The viewer can be comfortable looking into the room. The cat, however is in a stance of hostility. It goes along with Olympia’s unwelcoming facial expression….” read more: http://thestarvingarthistorian.wordpress.com/2010/10/31/great-remixes-in-art-history/

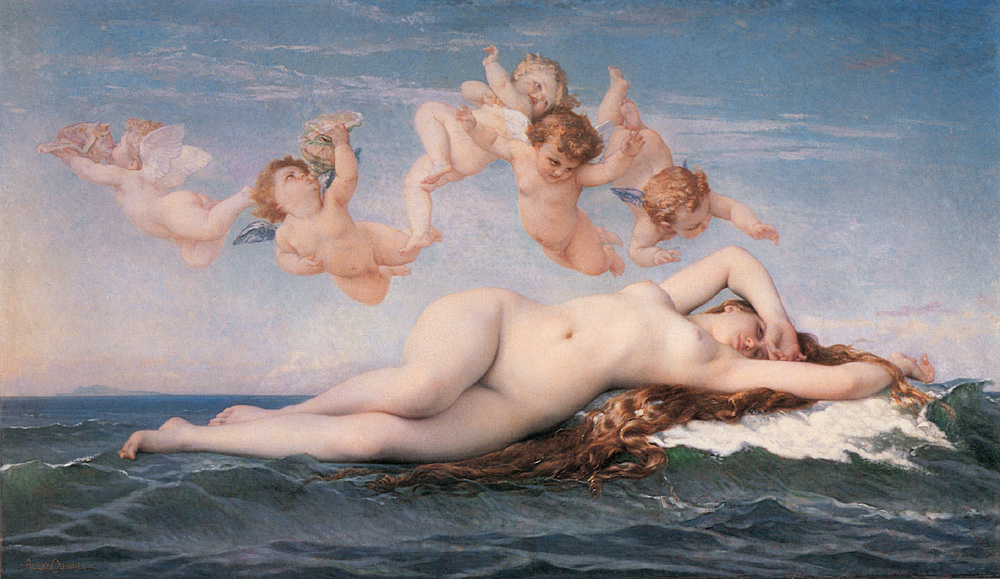

Armies of nudes swarmed across the Salon walls , pretty girls without a stitch on but elaborately disguised by titles. A bourgeois society obsessed with the surface observance of a moral code unsympathetic to the display of the body found the most delicious release in artistic subterfuge. The Emperor Napoleon III himself bought Cabanel’s “Birth of Venus” out of the Salon in 1863, yet in 1865 Manet’s “Olympia” was a scandal for its “indecency”.

“Cabanel’s Birth of Venus (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) created a sensation at the Salon of 1863, which was known as the “Salon of the Venuses” because several paintings of the goddess were exhibited. This painting embodies the ideals of academic art in its careful modeling, polished surface finish, and mythological subject. Cabanel’s picture established his reputation, and it was purchased by Napoleon III for his personal collection. In 1875, the American banker John Wolfe commissioned the present canvas, one of numerous replicas Cabanel made after the original. Source: Alexandre Cabanel: The Birth of Venus (94.24.1) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cabanel’s Folie-Bergere beauty suggests one thing and one thing alone; even the official critics found her daringly “wanton”. But since she was a Venus conventionally, and very skilfully painted by a ranking academician, everything was all right. The culture more than made up for the wantonness, and the lines of the picture were found to be of “great purity,” which helped. But Manet’s masterpiece was compared to “high” game and the people who gathered around it, to morbid curiosity seekers in a morgue. The latter comparison was not far from wrong, since they had come to see a “dirty” picture, the critics having given this label to “Olympia” because the model was boldly and objectively painted as a Parisian courtesan, unabashed. Honesty was always a dangerous topic in the Salon.

—

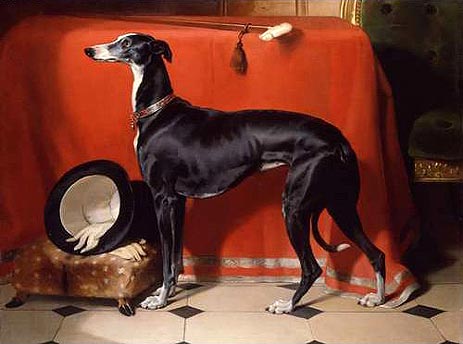

Eos, A Favorite Greyhound of Prince Albert

1841

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer

The Royal Collection London United Kingdom

44/56.3 in (111.8/142.9 cm) —Read More:http://www.topofart.com/artists/Sir_Edwin_Henry_Landseer/painting/827/Eos,_A_Favorite_Greyhound_of_Prince_Albert.php

The nude had been a standard test piece for centuries, but since art for art’s sake did not interest the Salon public, and since the nude for the sake of the nude was morally suspect, the Salon painters invented a hundred ways to involve nudes or semi-nudes in acceptable anecdotal situations. Psychiatrists would have no trouble explaining why these females got into so many painted difficulties . They were always being sold into slavery while prospective buyers subjected them to such indignities as examining their teeth. They were often put to the torture, lashed to stakes and the like, and they languished in prisons on heaps of straw while coarse guards stood by indifferently.

They couldn’t so much as disrobe for a quick dip in a woodland pool without being taken by surprise. Naturally, they resented all this, and their expressions of outraged modesty allowed the observers in the Salon to combine perfectly normal sympathy for the poor things with equally normal but less open response to their charms. Every figure in history who could conceivably be shown undraped or partially undraped was represented time and again. Then there were the nymphs, the bacchantes, and the other lively creatures who by tradition could not only go naked but could be sportive about the whole thing because, like Venus, they had been playing the culture secret since ancient times.

Children were almost as popular as nudes, and it was even easier to find things for them to do. Without question, the Salon produced in its simpering, mincing pictures of childhood the most offensively coy images in the history of painting. Animals were often painted in much the same vein, self-consciously engaged in being cute. At other times they were reproduced objectively enough, going about their normal occupations of grazing or just standing still. Cows and sheep held an unreasonable fascination for Salon painters and their public, explainable, possibly, as trhe urban person’s nostalgic recollection of a more tranquil pastoral age. The cow in the living room became a familiar phenomenon, and a painter’s knowledge of bovine anatomy was commented on as seriously as other painter’s knowledge of the human figure.

Rosa Bonheur in France and Sir Edwin Landseer in England were the most conspicuous

al painters. Landseer could give a stag at Eve all the pompous air of an eminent clubman and his dogs were noted for their sensitive intelligence and subtle emotional responses. Landseer pushed his special variation of the pathetic fallacy to new uncharted limits; his animals ran the emotional gamut as wide as that of the French nudes. He was not so much a painter as he was the Sarah Bernhardt of taxidermy.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS