Hemingway’s story on his visit to Spain in 1959 got out of control and became a rambling mass of words, a tangle of literature nearly three times longer than the forty thousand words Life magazine had agreed to print. Hemingway kept struggling with it; a free form novel cutting back an forth between two worlds and he found himself unable to axe it down or bring it up to the competing standards at loggerheads in his mind. Finally, the revisions had to be made by Aaron Hotchner and the magazine editors.

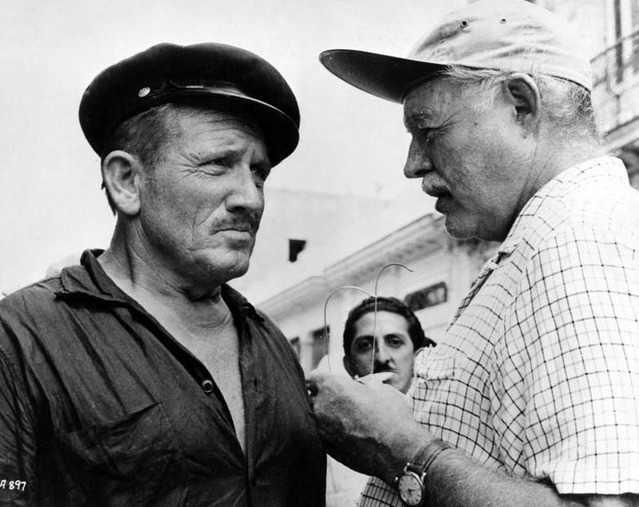

—Spencer Tracy and Ernest Hemingway spend time together during filming of “The Old Man and the Sea”—Read More:http://forums.tcm.com/thread.jspa?messageID=8684843&tstart=0

During the year that followed his last grand summer, Hemingway’s body was visibly dwindling away and his mind suffered even more. One might apply Jung’s words to him and say that the traits of character he concealed from the world and repressed into his unconscious were rising again to haunt him in outlandish forms. Always suspicious of people’s motives, he now began to dream of a vast conspiracy against him in which most of his friends had involved themselves after selling out to the FBI.

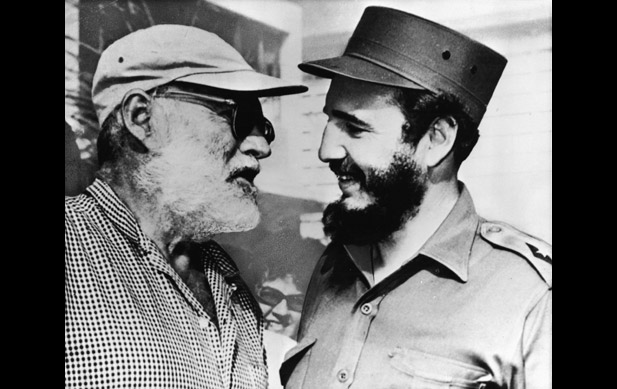

—Ernest Hemingway converses with Castro in 1959. A year later, Hemingway would be forced out of his house in Cuba due to political tensions. The American author moved to Idaho.—Read More:http://www.biography.com/people/fidel-castro-9241487/photos/fidel-castro

Hemingway would leave a restaurant in the middle of dinner if he saw two strangers drinking together. “Those two FBI men at the bar,” he would say in a low voice after looking hard at two traveling salesmen. “Don’t you think I know an FBI man when I see one?” He had other fears of dying in penury or of being clapped into jail for mild infractions of the game laws. His lifelong aggressiveness and his killer instinct were being turned against himself, the last of his possible trophies.

Still, after relinquishing the manuscript of The Dangerous Summer, he went back to his writing table every morning in the effort to finish another book that might, in this case, be truer than life. He regarded writing as a trade that was never to be mastered, and he said more than once, “I’m apprenticed out at it until I die.”

In the spring before Hemingway’s death, he was planning to revise A Moveable Feast, but found he had been too deeply wounded to write even a single line. He simply couldn’t do it. It was a confession of failure that came almost at the end; for every practical purpose it was the end. In one respect and only one, Hemingway resembled Hart Crane, who was born on the same day and whom he outlasted by nearly thirty years: both of them felt that if they couldn’t write, they didn’t want to live.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS