The Gods in art. Andre Malraux, with his Metamorphosis of the Gods, sought the key to humankind’s fate by a philosophical study of all the world’s art…

Sacred art in antiquity. It united mortal man with Eternity-but Greece brought the gods into daylight and Rome let them die. …

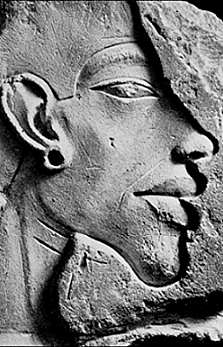

The high ridge of Andre Malraux’s first slope is what he called the Sacred- the art of the ancient Orient up to an including Egypt. Malraux’s view of the function of that art was perfectly expressed in this remark about the Sphinx and the Pyramids: “These giant forms rise together from the small funeral chamber which they cover up, from the embalmed corpse which it was their mission to unite with eternity.” In short, the art of the Sacred was predominantly funereal, its aim being not to show man in the here-and-now but to ease and express his transition to the beyond. The practitioners of that art for the most part shunned realistic representation, not because they were incapable of it, but because it was forbidden by the strict conventions of their religion.

—The king’s face, unprepossessing yet radiant, became known to all, but his identity remained a mystery. The Table of Dynasties drawn up by Brunet de Presle for his book Examen critique des Dynasties égyptiennes published in Paris in 1850, was inspired by a course given by Jean-Antoine Letronne at the Collège de France from 1833 to 1836. Under the heading “Eighteenth Dynasty”, de Presle lists: “Thutmose IV-Amenophis III (Memnon) – Horus (his son) – Thmaumot (his daughter) – Ramses I(…).” As recorded by Manetho, this King Horus, son of Amenophis III, corresponds with the Horus father of Achenkeres, the ninth king of the dynasty, reigning from 1674 to 1637 BCE. Horus probably represents Horemheb, Tutankhamon’s successor and the predecessor of Ramses I. No mention is made, then, of Akhenaten, Tutankhamon or Ay;….Read More:http://www.bergerfoundation.ch/Akhenaton/en/resurrection.html

The most celebrated “realism” in all the Orient was that of Tell el-Amarna, yet its colossus of the great Akhnaton( Akhenaten), when compared to Akhnaton’s death mask, shows a human face transformed into the elongated, mysteriously smiling countenance of the demigod. Like Akhnaton’s colossus, the statue of the Pharaoh Zoser of the Third Dynasty represents the face of the Sacred.

“Nothing remains of the power that caused Egypt to emerge from prehistoric night; but the power that caused the statue to emerge from it speaks to us with a voice as strong as that of the masters of Chartres, or of Rembrandt. We no longer have anything in common with the creator of that statue, not even the sentiments of love or death- perhaps not even a way of looking at his work; but when we are faced with this work, the accent of a sculptor who was forgotten for five thousand years seems to us to be as invulnerable to the rise and fall of empires as the accent of mother love.” ( to be continued )…

—Finally, one June day in 1887, a peasant living in the vicinity of Tell el Amarna took up her daily task of digging in the mounds of mudbrick debris in search of sebakh, the nitrous compost used by the village people in Egypt to fuel the fire. At the foot of a levelled wall, she discovered hundreds and hundreds of clay tablets covered with mysterious signs. Stacking a few of them in her veil, she showed them first to the neighbors, and then to a local official who, as a figure of authority, was expected to have all the answers. Apparently, this particular one was too imbued with himself to cast an eye at a few modest briquettes, so he had the petitioner led away. But determined as she was to make a few piasters out of her discovery, our peasant woman loaded her son and two donkeys with all the tablets she could muster and journeyed to Luxor, in the hopes of encountering a less arrogant mamur. Upon her arrival, alas, all that was left in one piece in her bundles were several dozen tablets, for the rest had been reduced to dust along the bumpy road. She showed two of them to an inspector who, at last, did take the matter seriously and had the samples studied. To the general astonishment, it turned out that she had come up with the diplomatic archives belonging to the court of Amenophis IV. What a bitter disappointment it was, then, when the poor soul had to admit that four/fifths of her load had been wiped out.—Read More:http://www.bergerfoundation.ch/Akhenaton/en/resurrection.html

COMMENTS

COMMENTS