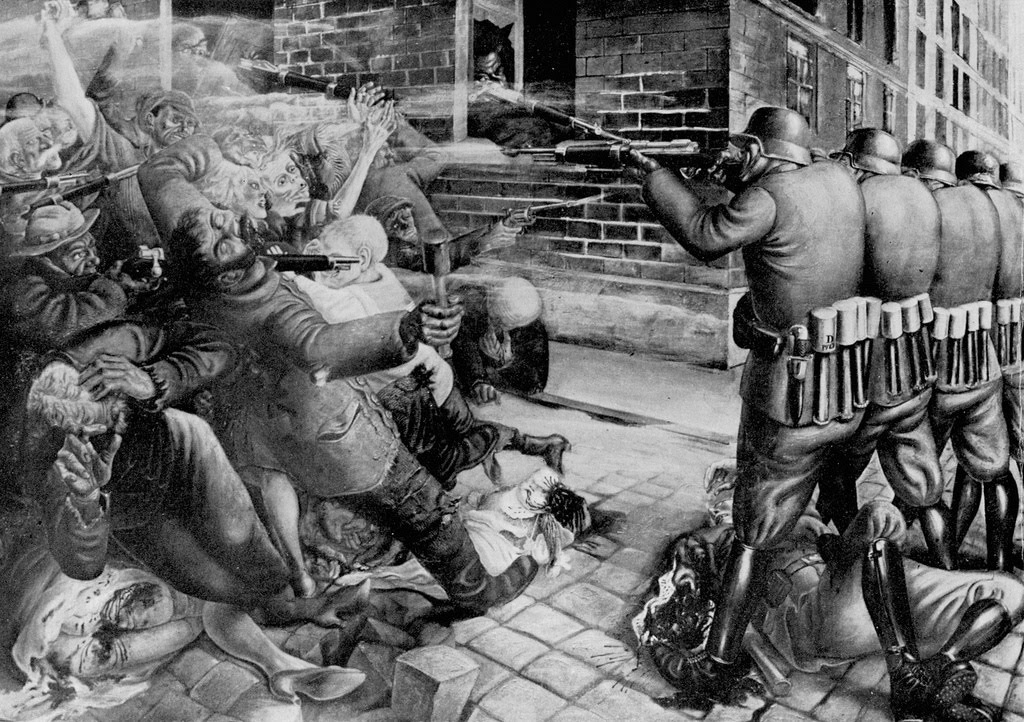

The nature of evil, the mechanical moving parts that make up villainy.The question is always posed, so that the question reveals the answer: if humanity collectively does want evil, then why does it exist? The short answer is that goodness is true and everlasting while evil exists as a negative, some even the Almighty doesn’t want, which means its existence is flimsy and temporal in nature, a non-entity of sorts; as a C.S. Lewis would say, by doing evil acts, we give evil more credit than it merits. Lousy decisions make evil into a more pervasive and insidious reality, a sort of handicapped and suffering existence than it really is. In the end, it sound somewhat Hollywood: evil can’t prevail since it is an unwanted phantom or temporary illusion, a rickety facade prone to auto-dissipation and destruction no matter how mennacing it presents itself.Certainly history has seen some wicked empires crumble, of which Communism and Fascism come easiest to mind; goodness eventually shines through. The key word being eventually.

God was sitting on his throne the other day

Looking round on a cloud

He was looking for something important to do

Something big and loud

Big bang, big bang

Big bang went the thing that created you and me

Mysterious things began to happen out in space

The Lord was cooking with a smile upon his face

He threw in a blessing

And he added a curse and said

I’m gonna create the universe

With a big bang, a big bang

Big bang went the thing that created you and me

The devil was given the job of looking after man

And the fire and the water and the air

But he used the power

To change the plan…( Big Bang, Godley and Creme)

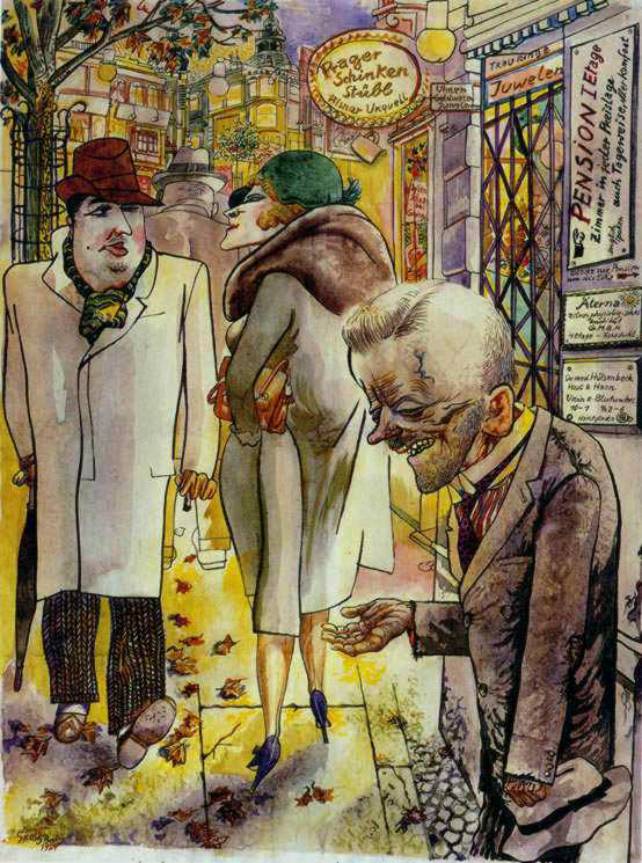

—George Grosz (1893-1959) was born in Berlin, Germany. He volunteered to fight in World War I, called “the war to end all wars,” but was discharged in 1917. He had become quite disillusioned with war, as had a group of young German artists he would soon join.

After the end of World War I, there was civil unrest in Germany, fighting between different groups trying to gain political power. Grosz fought in what was called the Spartakus uprising in 1919, and joined the communist Party. He left the CP within a few years, disillusioned with its dictatorial style of politics.—click image for source…

G.K Chesterton was a specilaist in paradox, and in this excerpt he turned his police chief Valentin into a murderer and an anti-religious fanatic:

The borderland of the brain, where all the monsters are made, moved horribly in the Gaelic O’Brien. He felt the chaotic presence of all the horse-men and fish-women that man’s unnatural fancy has begotten. A voice older than his first fathers seemed saying in his ear: ‘Keep out of the monstrous garden where grows the tree with double fruit. Avoid the evil garden where died the man with two heads.’ Yet, while these shameful symbolic shapes passed across the ancient mirror of his Irish soul, his Frenchified intellect was quite alert, and was watching the odd priest as closely and incredulously as all the rest.

Father Brown had turned round at last, and stood against the window, with his face in dense shadow; but even in that shadow they could see it was pale as ashes. Nevertheless, he spoke quite sensibly, as if there were no Gaelic souls on earth.

‘Gentlemen,’ he said, ‘you did not find the strange body of Becker in the garden. You did not find any strange body in the garden. In face of Dr. Simon’s rationalism, I still affirm that Becker was only partly present. Look here!’ (pointing to the black bulk of the mysterious corpse) ‘you never saw that man in your lives. Did you ever see this man?’

He rapidly rolled away the bald, yellow head of the unknown, and put in its place the white-maned head beside it. And there, complete, unified, unmistakable, lay Julius K. Brayne.

‘The murderer,’ went on Brown quietly, ‘hacked off his enemy’s head and flung the sword far over the wall. But he was too clever to fling the sword only. He flung the head over the wall also. Then he had only to clap on another head to the corpse, and (as he insisted on a private inquest) you all imagined a totally new man.’

‘Clap on another head!’ said O’Bri

taring. ‘What other head? Heads don’t grow on garden bushes, do they?’‘No,’ said Father Brown huskily, and looking at his boots; ‘there is only one place where they grow. They grow in the basket of the guillotine, beside which the chief of police, Aristide Valentin, was standing not an hour before the murder. Oh, my friends, hear me a minute more before you tear me in pieces. Valentin is an honest man, if being mad for an arguable cause is honesty. But did you never see in that cold, grey eye of his that he is mad! He would do anything, anything, to break what he calls the superstition of the Cross. He has fought for it and starved for it, and now he has murdered for it. Brayne’s crazy millions had hitherto been scattered among so many sects that they did little to alter the balance of things. But Valentin heard a whisper that Brayne, like so many scatter-brained sceptics, was drifting to us; and that was quite a different thing. Brayne would pour supplies into the impoverished and pugnacious Church of France; he would support six Nationalist newspapers like The Guillotine. The battle was already balanced on a point, and the fanatic took flame at the risk. He resolved to destroy the millionaire, and he did it as one would expect the greatest of detectives to commit his only crime. He abstracted the severed head of Becker on some criminological excuse, and took it home in his official box. He had that last argument with Brayne, that Lord Galloway did not hear the end of; that failing, he led him out into the sealed garden, talked about swordsmanship, used twigs and a sabre for illustration, and — ‘

Ivan of the Scar sprang up. ‘You lunatic,’ he yelled; ‘you’ll go to my master now, if I take you by — ‘

‘Why, I was going there,’ said Brown heavily; ‘I must ask him to confess, and all that.’

Driving the unhappy Brown before them like a hostage or sacrifice, they rushed together into the sudden stillness of Valentin’s study.

The great detective sat at his desk apparently too occupied to hear their turbulent entrance. They paused a moment, and then something in the look of that upright and elegant back made the doctor run forward suddenly. A touch and a glance showed him that there was a small box of pills at Valentin’s elbow, and that Valentin was dead in his chair; and on the blind face of the suicide was more than the pride of Cato. ( G.K. Chesterton, The Secret Garden, 1910)

…But can it be understood why bad things happen to good people, and why the distribution of both evil and good seems as unjust and random as it may appear? One answer to this enigma is to place the idea within the context in which divine justice concerns generated by evil are due to one having adopted a very limited and restricting focus; that is, looking only at certain features of the world while negating others. Within a broader perspective. One

can therefore alleviate those concerns by broadening one’s perspective and considering more or a variety aspects of creation. One can then perceive that the world is, on the whole, good, albeit not completely satisfactory.

There is still that nagging the central question of the problem of evil: why do good upright people sometimes suffer and why do the wicked and villainous types seem so often to prosper? In order to be satisfied that such chronic recurrences are compatible with divine justice, one wants to hear more than the basic response of “such things do not really happen very often,” as if they are trifles, insignificant within the cosmic drama of events, or that they make some vague and at-a-later-date contribution to the overall weel-being and goodness of the universe to be karmically harvested sometime in the future. Then even if God is not the cause of such evils, why does he even permit them at all?…

COMMENTS

COMMENTS