…Our notions of the future have not only varied,they have also changed greatly in the course of time. The future, if nothing else, has a past-our own conception of it included.

The modern future was born, according to one precise dating, in the year 1770, when a Parisian hack writer named Louis-Sebastien Mercier wrote a book called L’an 2440. In that genuinely pioneer work, which had no imitators until 1790, when another Paris scribbler wrote L’an 2000, M. Mercier set out to predict, on the basis of current trends, the blissful state of human society, that is, Paris, 670 years thereafter.

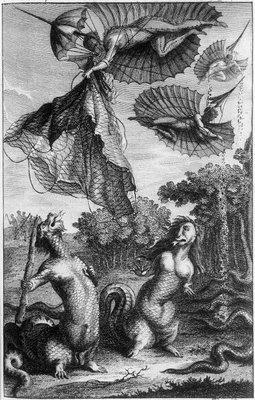

—Louis-Sebastien Mercier – The Year 2440, A Dream if Ever There Was One (1771): In Mercier’s time travel novel, a discontented Parisian falls asleep and wakes up in the year 2440. The world he awakens to is, for him, a utopia. The clergy has been reduced, slavery ended, and Paris has become orderly and clean. Writers have been elevated to the ultimate position of respect, but morality has been universalized. Morals are disseminated to the public in the theater, and writers who contradict that morality are reeducated by the state’s censors.—click image for source…

Previous utopian authors had set their imaginary commonwealths in remote, imaginary places. It was Mercier’s great distinction to set his in the remote, imagined future. Therein lies the modernity of his conception; which it must be said, he had compounded, with a popularizer’s rude vigor, from the hints and suggestions of contemporary French philosophes.

What Mercier assumed in his work, first and foremost, was an idea unknown to previous ages: that every single human institution is the product of continuous change in the past, a process that will go on unabated in the future, continually producing novelties. That assumption,essential to the modern conception of the future, is a commonplace today, but its validity is far from obvious. The most natural conception of one’s world is not its susceptibility to change but its awful permanence: I will die, yet the world will abide; my death will leave a gap, yet others will fill it.

As the anthropologist Robert Redfield observed: “In primitive societies uninfluenced by civilization, the future is seen as the reproduction of the immediate past.” The Maori’s future will hold his descendents who will resemble his ancestors. Even Francis Bacon, the first modern man to imagine that the future promised great novelties, was thinking only of technological marvels.

The individual’s mortality in a durable world is one of the prime facts of human experience, and that is why the reformer is so distinctly a modern type. In a world whose chief quality is seen as its permanence, reform agitation is barely distinguishable from criminal subversion. Even the great reformers of the past, Solon, Lycurgus, Hammurabi, were not reformers in the modern sense; they saw themselves as the givers of lasting, unchanging Law. ( to be continued)…

COMMENTS

COMMENTS