T.S. Eliot a reactionary?

The charges of fascism were of course brought against Eliot, and also against Yeats, Lawrence, Pound, and Wyndham Lewis for that ,matter, part of the romantic tug towards purity and blood one can imagine, the kind of turning a new page, tabula rasa that held to the point of fetish the notion of nihilism and the unlimited coneptualization that artists like Duchamp were brining to the for. Eliot, didn’t on the evidence of his poety, care much for the Jews, probably throygh fear and lack of a a grey material inventory to begin to comprehend an even greater conceptual framework that he could grasp; albeit there is no overt anti-Semitism in the Waste Land as there is in Geronton and “Burbankwith a Baedeker, Bleistein with a Cigar.” There is however the suggestion that the mongrelizing of Europe is the work of these wanderers, “hooded hordes”, and the exiles who have made a kind of culture out of money, in an effort by Eliot of trite superficials passed as razor-sharp insight that recysles hack tropes. There is a sort of subdued desire for a pure Aryanism, best realized in the civilization of India.

—In sum, Revri’s abstractions heal the wound Kandinsky and Mondrian unwittingly inflicted on abstraction by dividing it into irrational gestural and rational geometrical parts. They thus symbolize what T. S. Eliot famously called the dissociation of sensibility, that is, the separation of irrational passion and cognitive reason, setting them in seemingly perpetual conflict. Eliot regarded the dissociation of sensibility as the disease of modernity, and the sign of mental disease in general, suggesting that Kandinsky’s violently irrational and Mondrian’s ingeniously rational abstractions are peculiarly diseased, and as such spiritually defective. In contrast, Revri’s abstractions are spiritually effective,—Donald Kuspit. click image for source…

Eliot’s brand of indianism, incidetnally, makes no appeal to the young, who prefered the Buddhism of Eliot’s contemporary Hermann Hesse to the active philosophy of the Upanishads. Both Hesse whom Eliot had read, and the poet who was eventually to find, like a Malcolm Muggeridge, a kind of pretext for his being i the satisfactory faith of Anglo-Catholicism, saw that Europe was collapsing, and that the only hope lay in the East. But Hesse was all for the opting out of pacific neutrality, bst realized in a Swiss canton, while Eliot proposed techniques for purgation and prayer and even, in The Rock, the Social Credit that Pound had espoused.

—Donald Kuspit:But a larger issue informs the development of anti-aesthetic postart, namely, what T. S. Eliot called the “dissociation of sensibility,” that is, the separation of thinking and feeling (ratiocination and sentiment were his terms), which he thought (correctly) was a pervasive issue in modernity. Duchamp’s preference for what he called “intellectual expression” (“art in the service of the mind”) over “animal expression” suggests that his anti-art is an example of such dissociation. The integration of thinking and feeling remains a general issue of selfhood, all the more so in modernity, when the split is celebrated and thinking elevated over feeling. This occurs in art with the split between minimal-conceptual art and expressionism, with the former regarded as inherently superior to the latter, at least in some quarters. I personally think the former is not as intellectual as it looks and the latter is not as animal (“Neue Wilden”) as it is supposed to be.—click image for source…

Ultimately of course, this sort of thing matters little. What matters is the power of language, the purification of the dialect of the tribe, the big magic of words that we do not always understand and to which Eliot himself, trance-like, found himself in the grip of forces, expressed by words he may not have really understood himself. Mystically, kabbalistically, a Jew hater like Eliot owed much to the Baal Shem Tov who so impressed his followers with the importance of the word, the spoken word: every physical word carries tremendous spiritual weight and reverberates with spiritual significance. Hence, is a spiritual sphere, angry threats are easily translated into real action. Problem with Eliot, is that he was so obsessed with relishing every bite of meat he could swallow at a sort of heavenly banquet he could not resist transforming himself into the very beast he was tormented by and bent on eating. The Baal Shem Tov,s conclusion is very fitting: “Man is found where his desire is found.”

But to give Eliot his due, though there are bigger and more ambitious poems than The Waste Land, it remains a miraculous mediator between the hermetic and the demotic. It was Pound who said that music decays when it moves too far away from the dance, and poetry decays when it neglects to sing. The Waste Land can be seen as a diverse recital performed by a voice of immense variety caught between a popular poem and the frontiers of alienation. But sing it does.

ADDENDUM:

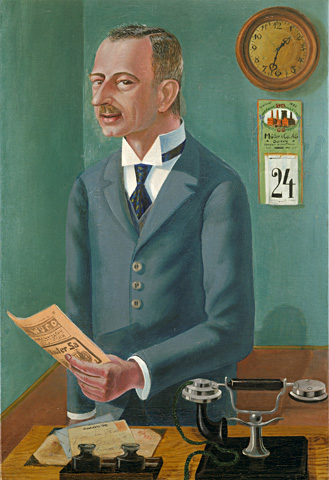

(seel ink at end)…Just as T. S. Eliot was fabricating his mythical Waste Land in 1922 in the aftermath of World War I — and the desolation that he felt was the inner truth of the roaring ‘20s and modern society in general — Dix was depicting the wasteland of the actual war in his own peculiarly mythologizing, outrageous, uncannily realistic way. What was intellectual poetry in Eliot — intellectualized fantasy, one might say, a sort of nightmare of stultifying decadence preached from the high pulpit of poetry as a moral lesson (Eliot almost always has a preacher’s punitive air; his ritualistic poems tend to read as sermons for the masses, promising to raise them up by telling them how low they have sunk, and thus how futile their existence is, how full of self-loathing and suffering it ought to be) — was ruthless intimidating prose in Dix, haunted by real death and suffering (not Eliot’s stylized and stylish — not to say forced and fake — numbness): Dix’s work belongs to the German tradition of the Triumph of Death — some of his images have a clear affinity with Baldung-Grien’s depiction of it — while Eliot metaphysicalizes death, as though it was not the brutal, factual, inescapably physical event it is. For Eliot death is an enigmatic idea rather than an everyday reality, a theme worthy of speculative poetry and philosophical discussion, while Dix makes its real effect — its destructive effect — on the body explicit. In a sense, Eliot compromises death by thinking about it, as though thinking would soften its blow, but Dix has seen it in action — experienced it up close and first-hand — in war. Death cannot be softened by philosophy and poetry: there is no consolation — conceptual and esthetic consolation prize — for it. Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/otto-dix3-24-10.asp

COMMENTS

COMMENTS