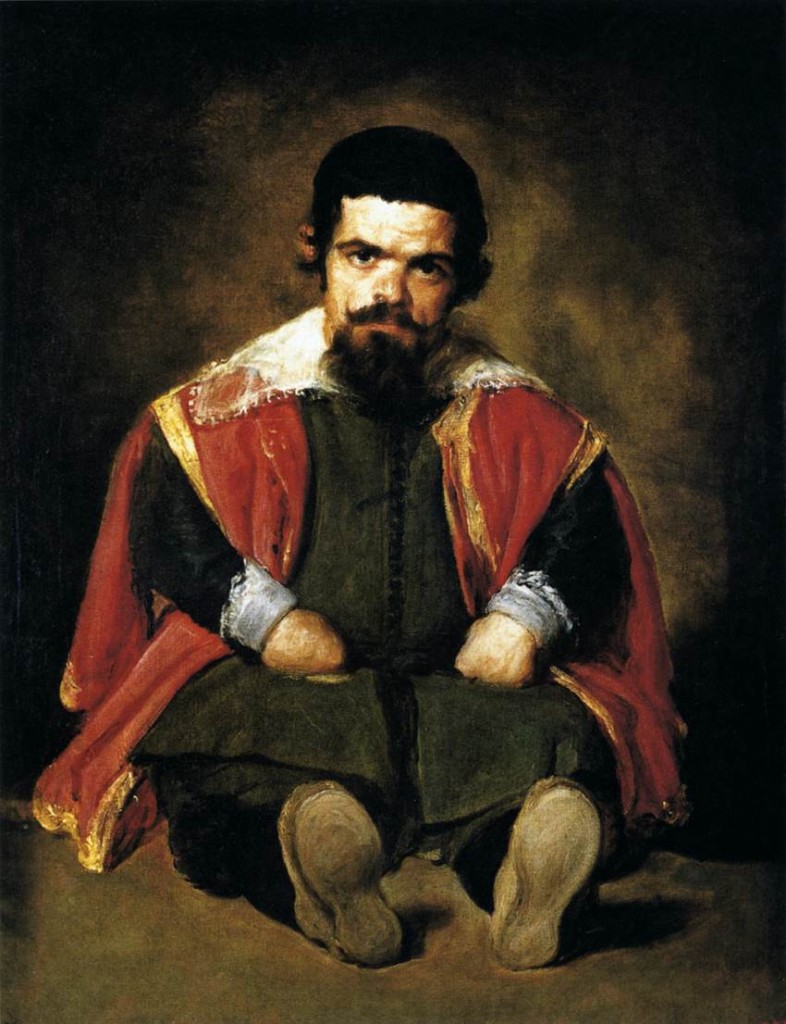

Put them all in a row. The famous dwarfs, or bufones: Don Diego de Acedo, a court official and not a jester at all, who set up to be the painter’s cousin and a man of letters, a tiny creature in black with a fur hat far too big, and cocked at an angle of defiance, who holds a book half the size of his body and who is fairly swelling with a secret importance, all against a background of wintry chaos; Don Sebastian de Morra, jester to the Prince Cardinal in the Low Countries, who fancied himself as traveler and man of the world; the idiot boy from Vallecas, Lezcano, said to have been born with all his teeth, here vacantly staring and holding some cards in his feeble little hands, used as the butt and recreation of young Prince Baltasar Carlos; and then Calabacillas, or Little Pumpkins, of imbecile appearance but with a turn of wit that Philip IV relished. All of them, in the nakedness of their despair and of their futile attempts to escape, have the power to excite horror and arouse campassion in us centuries after the ending of their short and luckless lives…

—For being a buffoon, this guy is most certainly not hilarious looking. His dog horse is certainly amassing. This painting is from Velazquez later period. During this time, Velazquez started loosening his brush stroke. He used proto impressionism techniques on the clothing.—click image for source…

And then, thinking of the King’s obstinate endeavors to make a hildago of Velazquez. No pains were spared, no euphemisms shirked, points were stretched to the point of bursting: wearisome research went on to prove the painter of pure Spanish blood, free from the Jewish or Moorish taint, a descendant of people who had never traded or served, an artist who painted by his sovereign’s order or to please himself, and never for vile money. All this was to make him acceptable to the Noble Order of Santiago, for which he was repeatedly proposed by Philip IV and as often rejected by the Order, with an obduracy which was no less rigid than the King’s and which provides a remarkable footnote to Spanish absolutism.

One can understand the attitude of the King, for rank seems all-important to those who have it and little beyond, but how to explain that of the artist? To be Velazquez, and to yearn to be “Don Diego”! Behold, what a piece of work is a man.

—Although the dwarf Don Sebastián de Morra is portrayed in full figure, he is not standing in a self-confident pose or elegantly seated on a chair, but is sitting on the bare earth with his feet stretched out in front of him. This low position not only shows up the sumptuous clothing for the clownish apparel it is, but also heightens the intended effect: the court fool is at the mercy of the spectator. Such pictorial devices reveal the voyeurism with which the royal rulers made these people the objects of their shameless whimsy, caprice and power. At the same time, however, the artist is also making another statement: this court fool is giving nothing away, neither a smile, nor any buffoonery. Immobile, scrutinizing and impenetrable, his dark eyes are fixed on the spectator, who somehow feels caught out by such a gaze and turns away.—click image for source…

ADDENDUM:

(see link at end)…As a painter in the Spanish court, it was the job of Diego Velazquez to portray the nobility of the court in the most favorable light. Yet Velazquez did not paint only kings and queens, but he also focused on even the most obscure members, such as the palace dwarves. It was not unusual to have paintings of dwarves, but the way in which Velazquez portrayed them makes his portraits distinct. For instance, Velazquez did not paint them as the mindless buffoons that people generally thought them to be. He portrayed them, instead, as intelligent and rational human beings. Furthermore, rather than focusing on the differences between the subject and the viewer, Velazquez emphasizes the similarities. Velazquez demonstrates the relation by using the Baroque technique of opening up the space in order to make the viewer feel more involved. Furthermore, Velazquez often paints his subjects against dark backgrounds and highlights their faces so that the viewer will acknowledge their mind and thoughts. One of the purposes of Baroque painting is to reveal and to apply the truth of God to the lives of the common people, which Velazquez seeks to do in revealing the humanity of the dwarves. Contrary to the prevailing attitude which treated the court dwarves as play things, Velazquez reveals their fundamental humanity.

During in 17th century, life in the Spanish court was stressful because the rules were so complicated and tedious. The court members constantly had to be on guard so as not to offend the royalty. One of the ways the Spanish nobility coped with this stress was through dwarves, who did not have to follow the same rules as the rest of the court. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, dwarves were known as curiosities, which means that they “were abnormal phenomena of the natural world which attested to the immense variety of divine creation” (Brown 143). Thus, the members of the Spanish court were intrigued and amused by their small size, but did not consider them important enough to follow the court customs. The dwarves were not just a diversion but performed another, much more demeaning role as well. Jonathan Brown writes that the dwarves were considered to be a negative affirmation of beauty, which they revealed by a perverse contrast; deformities of the mind and body were a way to measure and enhance the appearance of perfection. Thus, the reasoning went, a dwarf in the company of a king or queen pointedly emphasized the perfection of the ruler.

This sort of negative affirmation was appealing to the Spanish court,…Read More:http://www.lagrange.edu/resources/pdf/citations/2010/04Veatch_Art.pdf

COMMENTS

COMMENTS