European witch hunting. How can such lunacy have possessed humanity for two centuries? How could Europe’s educated laity, those lawyers, scholars and philosophers in the age of Erasmus cave in to such monkish phantasmagoria? The confessions of the so-called witches were worthless. But against massive systematic propaganda who could hold out? It is quite clear the witchcraft, as a systematic cult, was not discovered; it was invented by the inquisitors. The entire charade was an illusion that began its fabulous course burning thousands in its wake into epidemic proportions, particularly in Germany.

—Christians in medieval and pre-modern Europe believed that Satan was a real being and that Satan was actively involved in the affairs of humans. Satan’s goal was the corruption of humanity, the destruction of everything good, and the damnation of as many people as possible in hell. One means by which it was believed he accomplished this was through human agents to whom he gave supernatural powers.

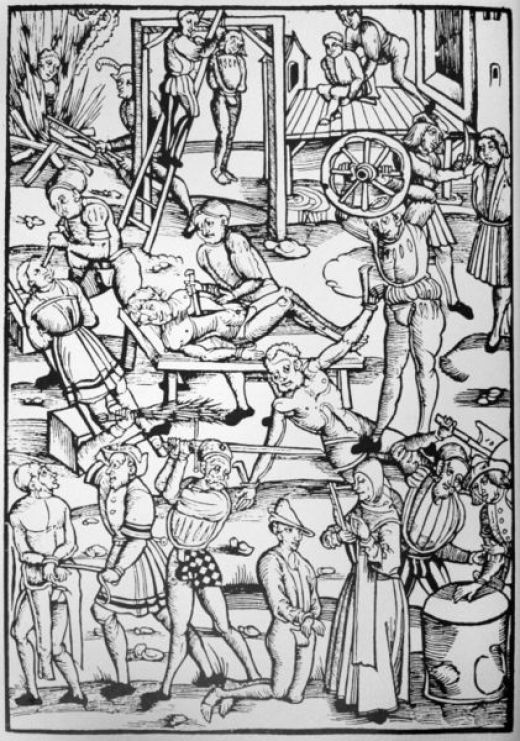

Witches were easily categorized as servants of Satan.—click image for source…

Finally, after two centuries, the lay spirit triumphed again, and belief in witchcraft, intellectually discredited, deprived of its organization and sanctions, no longer sure of the assent of rulers and judges, sank back again into its original, permanent character: a congeries of peasant superstitions.

—The classical period of witch-hunts in Europe fall into the Early Modern period or about 1450 to 1700, spanning the upheavals of the Reformation and the Thirty Years’ War, resulting in tens of thousands of executions.—click image for source…

The ultimate comfort in this squalid story of collective organized lunacy and cruelty is that the theorists of power maintain control: they create a separate caste in society- a Party, or the Elect- and arming it with a doctrine, an ideology, in which both slavery and nonsense can both be made permanent. Bertrand Russell once sadly confessed:

I am persuaded that there is no limit in the absurdities that can, by government action, come to be generally believed. Give me an adequate army, with power to provide it, with more pay and better food than falls to the lot of the average man, and I will undertake, within thirty years, to make the majority of the population believe that two and two are three, that water freezes when it gets hot and boils when it gets cold, or any other nonsense that might seem to serve the interest of the State. Of course, even when these beliefs have been generated, people would not put the kettle in the refrigerator when they wanted it to boil. That cold makes water boil would be a Sunday truth, sacred and mystical, to be professed in awed tones, but not to be acted on in daily life. What would happen would be that any verbal denial of the mystic doctrine would be made illegal, and obstinate heretics would be ‘frozen’ at the stake. ( Bertrand Russell. Unpopular Essays, 1950)

—These witchcraft trials were often dramatic and intense. In France, witchcraft cases centered around demonic possession, leading to sensational testimonies. The witch hunts in Estonia were usually combined with werewolf trials, often referred to as the “werewolf witch trials.” Although the witch craze began to wane by the 1600s, Scandinavia still had a series of tense witch trials in the 1600s, followed by Hungary in the 1700s.

Executions

Unlike in England and the American colonies, where the condemned witches were hanged, those convicted of witchcraft in other parts of Europe were burned at the stake.—click image for source…

The history of the European witch hunt shows this can indeed be done with liberal, humane and learned men like Jean Bodin and Nicolas Remy hanging and burning old women with the conscientious zeal of saviors of society. It is easy to see how completely an artificial system of nonsense, once established, can take possession even of thinking, rational men; and given the more contemporary Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, we can be tempted to wonder whether perhaps today our own minds may not be equally imprisoned, though in other prisons. After all, it is not only churches that manufacture myths and win assent to them.

On the other hand, the history of the witch craze also shows the limitations of delusion. Simply, it is not possible to fool all of the people all of the time, particularly in situations where political power requires economic development.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS