Miguel de Cervantes own account of his captivity by Algerian pirates is borne out by a contemporary who, in a history of Algiers written before Don Quixote had made its author famous, tells us that:

According to the testimony of Father Haedo, in whose curious and important work on the Topography of Algiers, published in 1612, we have the most valuable authority for this period of Cervantes’s life, and who was an eye-witness of the cruelties practiced in this pirates; den upon the Christian slaves, the captivity of Cervantes was one of the hardest ever known in Algiers. It was borne with a courage and constancy which, had there been nothing else to make his name memorable, must have sufficed to rank Cervantes among the heroes of his age an country. No episode more romantic is contained in the books of chivalry. No adventures more strange were encountered by any knight errant. Not Amadis nor Esplandian, notany of those whose fabled deeds has kindled his youthful imagination displayed a loftier spirit of honour or more worthily discharged his knightly devoir than did Miguel de Cervantes when inn duresse at Algiers. A slave in the power of the bitter enemy of his creed and nation, cut off in the hay-day of his fame from the path of ambition which fortune seemed to have opened to him, no lot could be more cruel than that which in the prime of his manhood and genius fell to our hero. Nor is there any chapter of his life more honourable than the record of the singular daring, fortitude, patience, and cheerfulness with which he bore his fate during this miserable period of five years. With no other support than his own indomitable spirit, forgotten by those whom he had served unable to receive any help from his friends, subjected to every kind of hardship which the tyranny or caprice of his masters might order, pursued by an unrelenting evil destiny which seemed in this, as in every other passage of his career, to mock at his efforts to live that high heroic life which he had conceived to himself, this poor maimed soldier was looked up to by that wretched colony of Christian captives…Read More:http://www.1902encyclopedia.com/C/CER/miguel-de-cervantes.html

Such was the Cervantes who, in 1580, returned from captivity to the Spain of Philip II. We can recognize him perfectly: he is a true, if somewhat belated, representative of the first of two different generations, the heroic, romantic, chivalrous generations of Charles V. But when he returned to Spain, what did he find? Already, while he had been breathing the heady air of Italy, fighting at Lepanto, braving his infidel captors in Algiers, the new generation was taking over in Spain, and now, instead of a grateful hero-king promoting him, accepting his advice, and leading an enthusiastic people into new crusades, he found only an atmosphere of growing weariness and disillusion.

—Or again, when Quixote and company find themselves at the infamous inn of Sancho’s blanket tossing, where they seek amusement in the story,”The Tale of Ill-Advised Curiosity,” only to have the narrative interrupted by Quixote in the throes of a dream about slaying a giant but really destroying some of the innkeepers wine skins. The moment the story stops, is of course, the moment after we learn that one of the tale’s main characters will die.

This technique not only builds suspense and tension, but says something about readers, too: They are not passive audience members, but participants in the story.

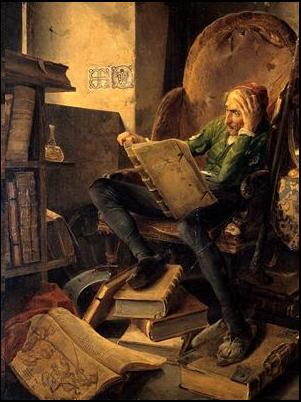

Keep in mind that Quixote himself is a reader-turned-participant in the extremest sense. …click image for source…

Year after year, Cervantes struggled to make a livelihood, first by poetry, then as a government purchaser, finally as a tax collector. None of these callings prospered. Economically, though not in spirit, for he retined, in every hardship, his own inexhaustible optimism- he sank down and down: bankrupt for small sums, excommunicated for trying to tax the clergy, finally imprisoned. In 1596, the year of the sack of Cadiz, he reached his lowest ebb, and wrote a wry, sardonic poem on that national humiliation.

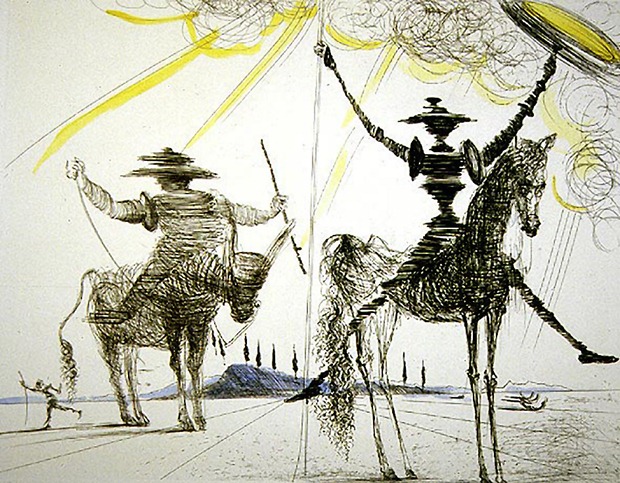

Two years later the death of Philip II drew from him an even more sardonic epitaph. Clearly the days of heroism were over: the days of disillusion had come. It was in those years of lowest ebb that Cervantes, in prison, conceived the idea of Don Quixote, the hero, the reader of romances, the Erasmian- for Don Quixote has many sly “Erasmian” touches which were duly pounced on by the Inquisition-who discovered that the real world- the world of narrow, materialist common sense- thought him mad.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS