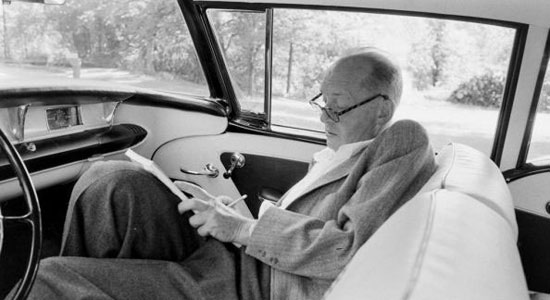

Most fiction pretends to be “real”: while we read, we believe. And the author himself, while he writes, also frequently believes. But there are certain stories that are contrived, and are meant to seem contrived, acting parts in which the actors do not believe. Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov is such a novelist….

Pale Fire was certainly not his best work, but it is one of his strangest in this special way. No one else could have written it, and few would have even thought of writing it. It is, or rather it pretends to be, a poem written by an American poet, published with a commentary by an expatriate European scholar; and the gimmick is that the commentary is all rubbish. Not only has it nothing to do with the matter and style of the poem, but it grows into an elaborate imaginative structure that is obviously absurd.

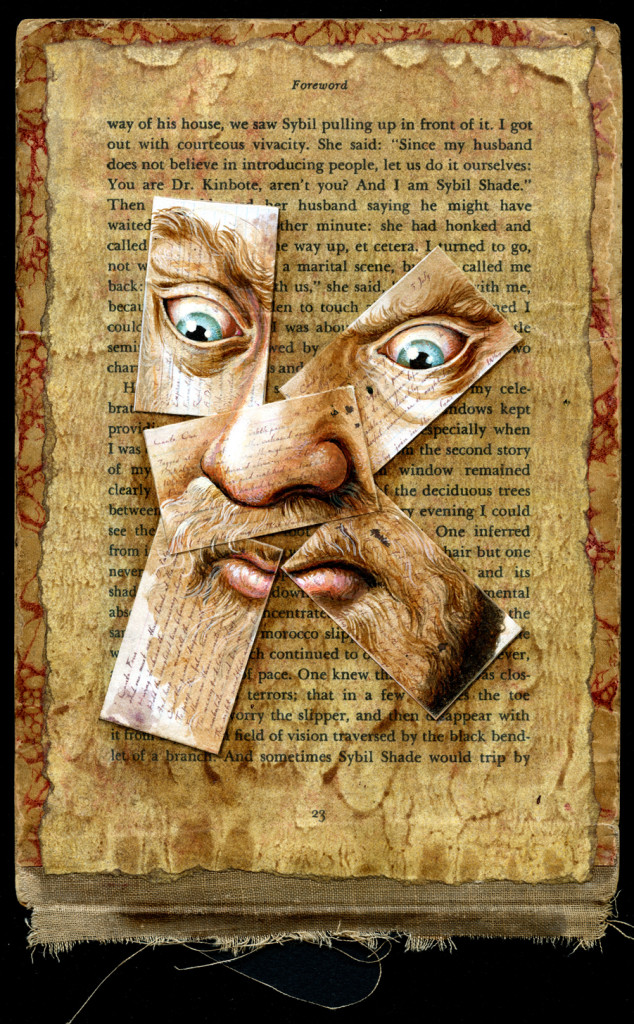

—For a while I was completely puzzled over how to portray Kinbote. But then it dawned on me that, according to Kinbote, Shade’s manuscript is written entirely on a series of index cards, so I decided to base the composition on 5 of these.—click image for source…

Nabokov gives us a story of two people: one sane and dead, the other insane and alive. The dead person is the old poet John Francis Shade. He was shot by an escaped lunatic; but he had finished, or almost finished, a handsome poem called Pale Fire- an autobiographical meditation in “heroic” couplets. The survivor. Dr. Charles Kinbote, comes from the European country of Zembla, which in some ways resembles Sweden. he is a philologist, lecturing for a year at Wordsmith College in New England; tall, bearded, vegetarian, inquisitive, endlessly garrulous, paranoiac, and homosexual. Having rented the house next door to Shade, he endeavors to move into Shade’s life, taking him for walks, begging for invitations into his home, and when rebuffed, spying on him with maniacal persistence.

— Nabokov is such a beyond genius, and Pale Fire is one big poem made out of the one big “poem” by old John Shade. It’s what the French call a mise en abyme.—click image for source…

When the old man tells him he is starting a poem, Kinbote actually suggests a subject to him- an absurd melodrama about an assassin’s pursuit of an exiled Zemblan monarch. After Shade’s murder, Kinbote gets the poet’s distracted widow to assign him editorial rights, and flees with the manuscript to a lonely place in the Rocky Mountains. There, without companions or advisors, he composes this gigantic commentary, which occupies most of the book. Almost wholly irrelevant, the commentary shows that Kinbote has no real interest in Shade’s poetry or understanding of it.

The very title, Pale Fire, comes from Shakespeare, but Kinbote cannot identify it because, out there in Utana near the Idoming border, he has no library. He has a copy of Timon of Athens, translated into Zemblan by Zembla’s national poet, but cannot trace the quotation there.

Instead of actually explicating the text of the poem, Kinbote uses it as a framework from which to draw three stories: the story of his own unhappiness at Wordsmith College, the outline of Shade’s life while he is working on Pale Fire complete with flashbacks, and the melodramatic escape and pursuit tale of King Charles of Zembla and the murderer Gradus. The stories interlock, though for a spell it is difficult to see what the adventures of the king of Zembla have to do with the peaceful life of New England. But Kinbote keeps pressing at it until he lets it out: he believes himself to be King Charles and, the escaped lunatic to be a revolutionary agent who was sent to kill him and blew a hole in the poet by mistake. ( to be continued)…

ADDENDUM:

(see link at end)…Vladimir Nabokov’s 1962 novel, Pale Fire, is widely considered a forerunner of postmodernism and a prime example of the literature of exhaustion. The novel has four distinct sections. The first is a “Forward” by a man who calls himself Charles Kinbote….

The novel, however, is something more than a satiric look at the solipsistic excesses of academic exegesis. Kinbote’s commentary gradually transforms the heterogenous elements of the text into a labyrinth of dazzling complexity. Kinbote’s status as a reliable narrator is subverted early in the book; by the end of the Forward, we suspect him to be something of an opportunist who has made off with Shade’s manuscript before the grieving widow can gather her wits. His commentary supports this suspicion. Shade’s poem seems to be a fairly straightforward bit of personal reminiscence, as unmarked by worldly concerns as it is by any hint of literary talent. Bending every word of Shade’s poem to ludicrous extremes, however, Kinbote proceeds to unfold the story of the overthrow of the last King of Zembla, Charles II. The story of Shade’s composition of the poem is made parallel to the story o

e approach of an assassin named Gradus who is coming to America to slay the exiled King.… using Shade’s poem as a means of telling his own story. However, even this possibility begins to slip away as a third and almost invisible narrator, a Russian emigré named Botkin, makes his way into the narrative, raising the possibility that the whole thing, Kinbote, Zembla, Charles II, Gradus, even Shade’s poem itself, might be the elaborate creation of this other figure.

Critics have spilled no small amount of ink trying to figure who is the true author of this text, which of these layers of story-telling is the real and which the fictional. In so doing they have unwittingly swallowed Nabokov’s bait; there can be no strict hierarchical ordering of these narratives because each is as “real” as the other. Or, to be more precise, each is as fictional as the other–Nabokov is openly toying with the desire to see reality as anything but a fictional construct.

Writers and readers of hypertext fiction will find much of interest in Nabokov’s comic novel. Like Pavic’s Dictionary of the Khazars, Nabokov foregoes the traditional form of the novel in favour of one usually seen as antithetical to narrative. The “Authoritative Edition” format of academic publishing allows Nabokov to re-think the conventions of the realist novel. His tale blurs the traditional distinctions between editor and manuscript, and between narrator and tale, in order to comment ironically on the very processes of reading and interpretation. As with a hypertext, the reader at first moves back and forth between Shade’s manuscript and Kinbote’s commentary, hoping to find the “truth” of this text by a close comparison of the two texts. However, this desire for closure is rapidly exhausted, as the reader realizes that each point of comparison, each link that is pursued, only takes him or her deeper and deeper into the open-ended web of Nabokov’s design.

Pale Fire instantiates many of the formal mechanisms of hypertext–its use of disparate materials connected together through an associative logic of links and anchors–only in order to signal the dangers of using these mechanisms to pursue the same old dreams of univocity and fixed meaning.Read More:http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/elab/hfl0244.html

COMMENTS

COMMENTS