The high spirits of the 1920’s. A circle of young exuberant wits regaled Dry-Era America from around a hotel table. Nothing quite like them has been seen since…

Frank Crowninshield, the editor of Vanity Fair, possessed charm and a flair for the modish few of his contemporaries could come close to. War, labor troubles, and scowling issues of the day were not what he might have referred to as his metier. He was shallow of mind and deep of heart, constant in his enthusiasms, and better at private pleasantries than at public crises. Not the hard boiled egg type, but a souffle that could rise graciously to any and every occasion; an archetype character that has been put in storage in our more pessimistic times.

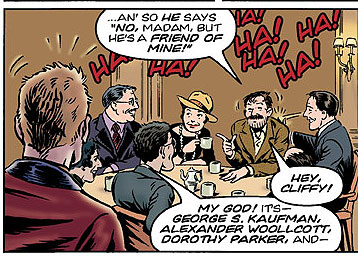

—Dottie and her pals make an appearance in the comic stip Jazz Age Comics. Is this a first for the Round Table in this medium?

History aside, George Gershwin wasn’t known to hang out with this group in the Twenties.

And where did Mrs. Parker get that hat? Indiana Jones?—click image for source…

He wanted life to be charming, bubbling and gay, and his magazine to be a cheerful and urbane month-by-month “record of current achievements in all the arts and a mirror of the progress and promise of American life.” Robert Benchley later observed that he would allow any entertaining writer to say practically anything in Vanity Fair so long as they said it in evening clothes.

Crowinshield belonged to the old school and yet anticipated the new. A traditionalist, he was also an innovator. He bootlegged artistic Europe with success into an aesthetically dry united States. He was one of those who helped open America’s at first somewhat baffled eyes to the beauties of modern art. He had a hazel-wand genius for discovering new, young talents. Warmheartred and politely impish, he liked the young because of his own lasting youth and welcomed their restrained impieties. He admired their freshness and did not object, anymore than Conde Nast did, to their being inexpensive.

Crowinshield compared himself to a literary lion tamer, finding it the safest plan to “deal with such felines when they are still cubs; to snare them, in traps, before their teeth have sharpened and their claws grown long.” High on the list of Vanity Fair lions that he could, and did point out with pride at a safer distance were Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley and Robert Sherwood. ( to be continued)…

ADDENDUM:

(see link at end)…Dining upon free popovers and celery sticks, or, in flush times, chicken hash with pancakes, the aforementioned writers—along with an ever-evolving cast that included playwrights George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly, columnist Heywood Broun, and author Edna Ferber—bantered and gossiped, played endless games of cribbage and poker, and devised elaborate practical jokes to deceive one another. Conversation was fast, clever and biting—hence the “vicious” nickname, though the Round Table moniker was widely used after a Brooklyn Eagle caricature depicted the group draped in armor around a circular table. (Not all were fans of the club: Groucho Marx, whose brother Harpo occasionally joined the group, distanced himself from the table, claiming “the price of admission is a serpent’s tongue and a half-concealed stiletto.”)

Of course, the Round Tablers also wrote—Kaufman, Connelly, and Sherwood all won Pulitzers for their work, and the Table’s wit was made famous nationwide in columns by Broun and Franklin Pierce Adams, who dutifully reported Tableside gossip in his “Conning Tower” column in the New York Tribune. Ernest Hemingway wrote his infamous “Baby Shoes” short story during a visit to the Round Table, collecting ten dollars apiece from the other writers who dared to bet he couldn’t write a complete tale in only six words.

But the most enduring legacy of the Algonquin Round Table was undoubtedly the creation of The New Yorker in 1925, the masterwork of editor and Round Table regular Harold Ross, who secured funding for the magazine at the hotel (to this day, Algonquin guests receive a complimentary copy of the magazine). Many Round Tablers contributed to the magazine, whose urbane, sophisticated tone mirrored the conversations at the Algonquin’s power lunches.Read More:http://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2012/08/27/power-lunches/

COMMENTS

COMMENTS