When simplistic views of the working class are no longer valid. The machine, in post WWI Europe, had not, after all, turned out to be the instrument of social liberation; and in just about every country in the world the hardhat had become the henchman of reaction, well beneath the ideal of Fernand Leger’s New Man, an idea on the cusp where the working classes would have the leisure to develop the new style of life that was there for the asking; hard to foresee that his lifelong love match with the working classes could be manifested in the most obscure form in that of man-made industrial age death camps and killing machines or the outright manipulation to pervert values and consume through the efforts of an Edward Bernays where a world of secular humanism and psychology could be put to the service and bidding of an industrial complex…

—Fernand Léger (French, 1881-1955). The City, 1919. Oil on canvas. 91 x 117 1/2 in. (231.1 x 298.5 cm). A.E. Gallatin Collection, 1952. Philadelphia Museum of Art.—

Fernand Leger was of course, very careful, at the start not to sentimentalize the working man, or to assign him a more important place in the cities of the future than he would actually occupy.

In the great metropolitan paintings that Leger produced in 1919 and 1920, above all, The City, human beings play a subordinate part. Objects among other objects, they are not individualized: individuality was kept for moments when, as in The Mechanic, the working man was off duty and could smoke a cigarette. But he was not diminished, in Leger’s eyes, by his objecthood. Rather, it raised him to the same level- that of a functional elegance, a stripped-down beauty without precedent- that was the mark of every other element in the new metropolitan scene.

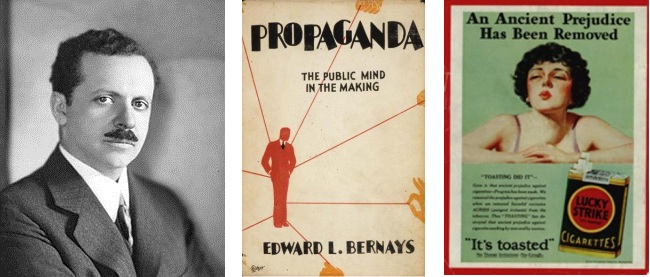

—Bernays himself emerges as a remarkable character. He not only was able to sell the American people anything – he made it cool for women to smoke and for children to love soap and for eggs to accompany bacon – his skills also could win elections and change the course of foreign policy. In one extraordinary sequence, Curtis shows how Bernays single-handedly toppled the popular Guatemalan government with one or two publicity stunts, playing on Cold War fears, and acting on behalf of a banana corporation.

He shows, too, how the principles of Freudianism, initially through Bernays, had a profound effect on corporations and governments, and led directly to the new all-pervasive ideas of market research and focus groups – psychoanalysis of products and ideas.—click image for source…

Not everyone, of course, looked with such favor on the first machine age. In the early 1920’s Karel Capek’s R.U.R. was welcomed in theatres all over the world for its defeatist preview of robot society. In 1932 Rene Clair’s A Nous la Liberte was enormously popular for its portrait of the dehumanizing effect of industrialization. Chaplin’s Modern Times ( 1936) is a further and definitive example of this same disenchantment. Still Leger did not stand alone in his optimistic approach to the problems of the postwar world. In the social strivings of the 1920’s the machine had a fundamental, and it was hoped a benevolent part to play.

—Fernand Léger (French, 1881-1955). The Mechanic, 1920. Oil on canvas. 45 5/8 x 35 in. (115.9 x 88.9 cm). Purchased 1966. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

© 2009 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris—

But, as Leger showed, this new machine age world, the glamour as seen in Italian futurist work, was also disturbingly unreal which underlined the difficulties and the impossibility of finding a natural habitat in a world where there is no subjective foothold to grasp. Call it investing feelings into the indifferent and meaningless, a world of outer reality subject to delusions. Or, as Bernays knew, the human intellect has difficulty accepting separation which provides a multitude of pretexts and contexts for falling in love or being obsessed with the “other” in the environment as a tonic to this alienation: ideas, beliefs, lifestyles, consumer goods, pop culture, and the star system-idolatry in a world devoid of subjective nuance characterized by an emptiness that is not really alive but serves as a distracting function, as unconvincing and as facile as it may be….

COMMENTS

COMMENTS