Shapes and shadows harboring within the terrors of the modern world. Dehumanized. Alienation and isolation in all places and within every context. Like Josef K being slandered,”without his having done anything bad, he was arrested one fine morning.” The spirit of the ghetto never really leaves Kafka as if it was the habitat of Jewish exile that had its counterpoint in his own view of Hradcany Hill, a kind of unknown beyond that permeates the central literary figures plunked within those settings butting heads with the monumental as nihilistic emptiness equated with the profit motive.

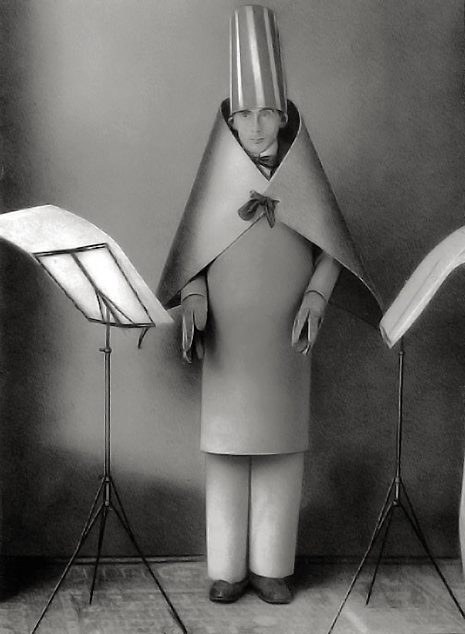

—Kafka used to say of himself that he was “ a nihilistic thought that came into God’s head.” Nihilism is certainly part of Kafka’s crucial notion of “violence”, where Kafka’s genius exposes many shades between the individual and the work of repression and terror. —click image for source…

Kafka likely had little notion of becoming a prophet, a visionary, but his vision of Prague, a kind of heartland of Western society of the European denomination seemed to contain all the dark terrors that haunt today’s world and much of a Christian society’s fullest flowering of its mass of contradictions, dead-ends and non-resolvable predicaments that displaced the God business for the capriciousness and exalted ego of man as navigator and captain of all moral compasses.

—As such, in Kafka’s writing the gestures of violence are mixed with the secrecy of places and the solitude of the individuals. For Kafka, the solitude is not only a state of living alone, but that of being lost in the modern world. It is an enduring condition of emotional distress in his characters who feel estranged, misunderstood or rejected by others. For a Kafkaesque individual evil is everywhere, and redemption is inaccessible.—click image for source…

The trial of the fictional Josef K. never really ends. It simply becomes a sentence. At the close of the novel K. is escorted to hisplace of execution, stopping for a moment on a small bridge where he looks lingering down on a small island. In the book, a knife is plunged into K.’s heart and, as though it were a ritual performed without passion, the knife is turned twice. But what of the crime? Circumstantially, K. did not exist of himself and strictly speaking, an individual defined by function. Utility. K. existed only insofar as he had some relationship to this Castle, a small fleck he was in the cosmos in rotation around the cosmos maintained in his trajectory either though indifference, trauma or hysteria under the objective gaze of the observer, but not concentrated since it slipped and slid way until everything becomes deeply lost in the twilight, like Gregor in the Metamorphosis, to be swept out with the rubbish by the maid.

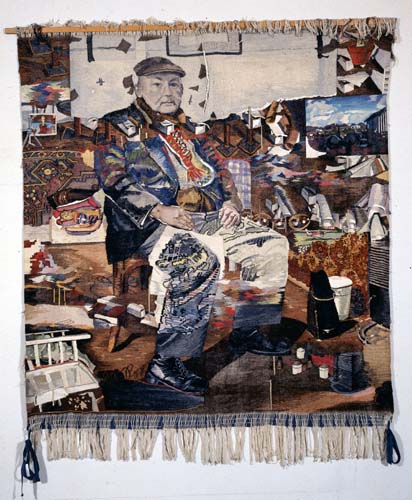

—Tinguely said he found poetry in the machine. Roth seemed to have found much more poetry in the destruction and chaotic wreckage Tinguely’s machine left in its wake. Homage to New York became instant garbage, suggesting what Tinguely thought of New York — certainly not such a nice, neat, well-ordered place as Basel — as well as of art and perhaps life in general. —click image for source…

ADDENDUM:

(see link at end)…Clearly, K.‘s declaration of his rights is part of the deception (or fate) he has spawned, and a deception with which the Castle itself is playing its own game, by indulging K.’s arguments. What we find throughout the novel, especially in K.’s encounters with the Castle’s authorities, is mutual deceit being played to the hilt, though, too, there is this one administrative certainty: “. . . the Castle always has the advantage.”

Kafka’s often-quoted assertion that “Man cannot live without an enduring faith in something indestructible within him.” His actual fate, however, as it pitilessly unfolds in The Castle, is a repudiation of this affirmation and attests to “the futility of resistance” and to the invincible power of the absurdity of living. K. himself is representative of “the condemned man” who is powerless before the ineradicable condition of despair, non-meaning, exclusion, isolation. For him there is no road to human dignity, no release from a

sentence of death, even as “enduring faith” is a platitude in a world that dictates extinction in a “small stone quarry, deserted and desolate,” as suffered by Kafka’s protagonist, the bank clerk Joseph K., in The Trial.

The fleeting thought of escaping from a “desolate country” is one that K. refuses to entertain, even when Frieda, his mistress, “a plain, oldish, skinny girl with short, thin hair,” begs him at one point to escape to France or Spain,

e the two of them would find some peace, some lesser tension and pressures of existence.What we come to see in K. is the depiction of what, as Kafka wrote to his friend Max Brod regarding the nature of his creative work,constitutes “a descent to the dark powers, an unchaining of spirits whose natural state is to be bound servants.” Indeed, K.’s life-story discloses his inability either to accept the condition of a “bound servant” or to undergo the inner travails of “the dark night of the soul” that lead to a purified and sanctified state of release beyond guilt and punishment—and beyond moral paralysis. Read More:http://www.nhinet.org/panichas17-1&2.pdf

COMMENTS

COMMENTS