Thomas Robert Malthus. Hunger is always at the door, even in an era like our own. People still die of starvation. Do people starve because there are too many of us ? Or, is famine the necessary companion, the price to pay for civilization? Was Malthus correct in his grim insistence that population must necessarily outdistance food supply? Or, in sum, is there more to famine than a lack of food?…

—Ensor took delight in macabre nightmarish fantasies, like the one he portrayed in The Banquet of the Starved. Guests sit around the Last-Supper style table, clad in grotesque masks and engaged in a variety of sinful activities, inspired by the German occupation of Belgium and accompanying period of starvation:

Above, The Banquet of the Starved, 1915. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. —click image for source…

In his intellectual wrangles with his father, Malthus refused to share the dream, the enlightened enthusiasms of human perfectibility. It was the cool Cambridge mathematician against the sentimental optimist, political economy against Jean Jacques Rousseau, and Malthus, obviously feeling that he had the best of the argument, determined to present it to a wider public.

The two radical utopians against whom Malthus particularly directed the arguments of the Essay on Population were the Marquis de Condorcet and William Godwin. There are few more striking testimonies to unshakable belief in human progress than Condorcet’s Sketch for a Historical Table of the Progress of the Human Mind, for it was written while he was in hiding from the French revolutionary government and completed shortly before his death and suicide.In the final part of his essay Condorcet looked to the future and saw there human happiness brought to a zenith by the triumph of reason and science.

—Van Gogh also admired Jozef Israels, a painter of fishermen and peasants whom van Gogh described to Theo as the “Dutch Millet”.

Jozef Israels, Peasant Family at Table. Oil on canvas, 1882. Approximately 28″ x 41″. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.—click image for source…

Condorcet’s English counterpart was Godwin, the husband of Mary Wollstonecraft, the father-in-law of Shelley, and, one might add, through the medium of his daughter’s imagination the grandfather of Frankenstein. Godwin had been reared in the tradition of English Non-conformity, ans some of the stark simplicities of that tradition clung to what he took to be the dictates of reason. Reason and natural justice were to be absolute sovereigns of human life, and what was left of the institutions of society- law, property, marriage- was very little indeed by the time Godwin had finished with them in Political Justice (1793). Godwin was not content with advocating;he was prepared to predict. In a state of equality the amount of labor required to support the frugal wants of rational men, “is so light as rather to assume the guise of agreeable relaxation and gentle exercise, then of labour.” ( to be continued)…

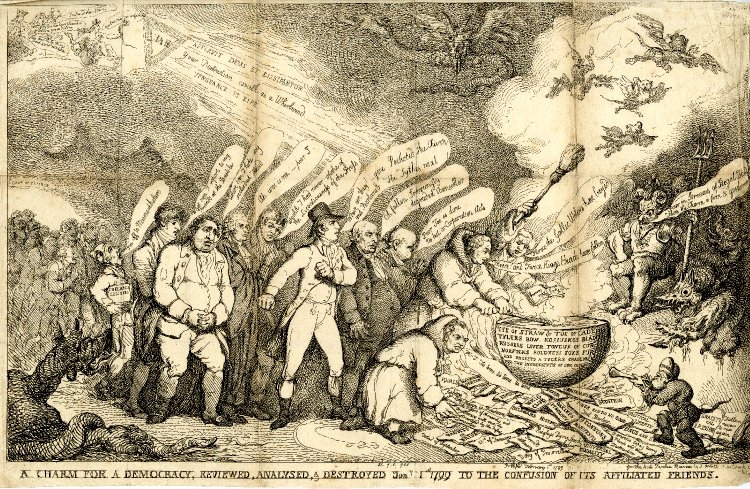

—The Anti-Jacobin’s prime target in 1798-99 was not the individual influence of the charismatic lecturer in any case, but Opposition newspapers and essayists. Apart from the usual Whig suspects, Thelwall’s companions in the New Morality’s procession of villains include Godwin, Coleridge, Southey, Holcroft, and Priestley besides representations of the Morning Chronicle, the Courier, the Star and the Morning Post. In A Charm for a Democracy (1799), produced by Thomas Rowlandson for the Anti-Jacobin Review, another motley procession of radicals presides over a seditious cauldron heated by a bonfire of Jacobin texts, including Thelwall’s Rights of Nature, to a fare blown by a newsboy from the Courier. But this is a print that celebrates radical defeat; it is anything but alarmist. —click image for source…

COMMENTS

COMMENTS