VENUS RISING: DROP DEAD GORGEOUS

She was the perfect beauty. Beloved of prince and painter, Simonetta Vespucci was the Renaissance ideal. …

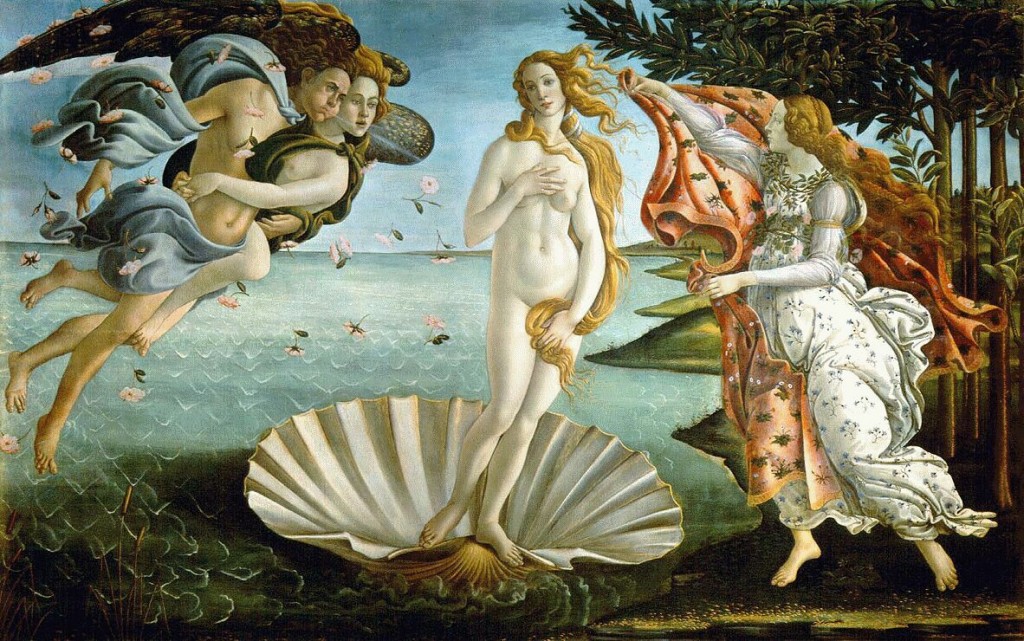

The visage of a ravishing, young woman appears again and again in the art of Sandro Botticelli, Early Italian Renaissance painter. It is a face that is almost as familiar to art lovers all over the world as that of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Botticelli’s model for his most famous art work, The Birth of Venus, was the beautiful Simonetta Vespucci. Once nominated “The Queen of Beauty” at a Florentine jousting tournament, it was Simonetta’s face that Botticelli painted on an art banner that was carried into battle by the tournament winner, Giuliano de’ Medici, a man soon to become her lover. Inscribed beneath her image, Botticelli described her as “the unparalleled one.” ( Brenda Harness )

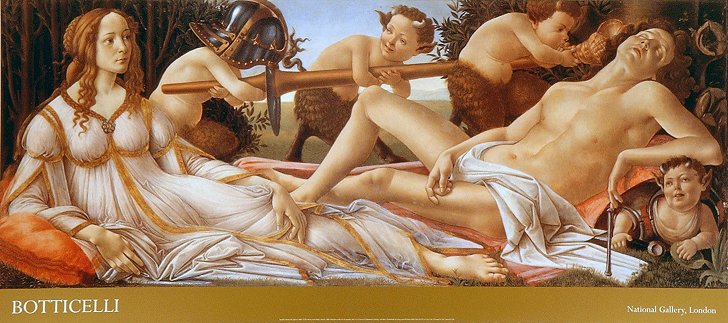

Botticelli. Venus and Mars 1483. "Over the centuries, the central figure of Venus/Aphrodite has become a symbolic depiction of innocence and idealised beauty. Botticelli's Venus, whilst instantly recognisable for anyone familiar with art, has one very special distinction - the depiction suggests the model was of great significance to the artist. It is here we must tread carefully in describing this attribution. It is a contentious issue in Art History, resulting in much furrowing of brows when one states that Botticelli's Venus was inspired by if not a direct portrait of Simonetta Vespucci(c.1453-1476)."

She was born at Porto Venere, near Genoa, precisely where the Italians believe Venus to have emerged from the blue waters after her birth in the Mediterranean. At her death at the age of twenty-two the city of Florence went into mourning, following her funeral train from the Palazzo Vespucci to the Church of the Ognisssanti. She lay in state while men and women alike walked past her bier with tears streaming unashamedly down their cheeks as they gazed for the last time at her long, silken, textured, honey coppered hair, the gold over fresh cream skin, remembering the wide-set, radiant and yet tender eyes, the features sculptured with the flawless symmetryof Donatello’s living marble.

"The degree to which we can ascribe the likeness to an infatuation held by Botticelli is subject to speculation. Among the most prominent detractors of the Botticelli-Vespucci theory is modern Historian Felipe Fernandez-Arnesto, who submits that due to a lack of a definitive document, ascribing that Botticelli's work was inspired by Simonetta Vespucci is a "vulgar assumption." It is unfortunate for those reading his books that Mr. Arnesto tells us little else of what he does see in Botticelli's works. "

The personification of ideal beauty was an important concept to Italian Renaissance artists like Botticelli who thought that outward beauty reflected inner beauty or virtue (spiritual beauty). Simonetta died young in 1476 at the age of twenty-two from tuberculosis, but Botticelli continued to feature her image in his art for the next three decades. All of Botticelli’s female art images were portraits of Simonetta, her face even appearing several times within some compositions. At some time before his death thirty-four years later, Botticelli requested to be buried at Simonetta’s feet. His request was granted and both are interred in the Vespucci parish church of Chiesa d’Ognissanti in Florence, Italy.

"Dancing amidst La Primavera are The Charites, or Three Graces - symbols of Beauty and Fertility since Antiquity. The fertilsation motifs and "plucking of fruit" produce the central image of a woman with child. On the right is Zephyrus and Chloris. The gust of wind from Zephyr's lips is indicative of the vital role of wind in the pollination of plants - and is hence a classic symbol of the process of fertilisation. Those familiar with the tale of Zephyrus and Chloris will understand that the initial union between these two was forced. This is believed to be an allegory of the marriage between the Lorenzo di Pierfranscesco De Medici and Semiramide D'Appiani - moreso a politically fortuitous match than one born of Love."

Who was Simonetta Vespucci who could arouse such adoration among the beauty drenched Florentines? The facts of her life are few , simple, and obscured in the mists of romantic literature. She was born Simonetta Cattaneo in 1453, of an old and noble Genoese family. Though their wealth was on the decline there was still enough money for her mother, Cattocchia di marco Spinola, to travel frequently throughout Italy, where she was connected by ties of blood and friendship with many of the great houses of Tuscany, including that of the ruling Medici.

It was when Simonetta had just turned sixteen that her mother betrothed her to Marco Vespucci . The Vespucci had been leaders of Florentine political life and trade since the fourteenth century. Their relationship with the Medici went back to the founder of that dynasty. Because of the decline in the Cattaneo fortunes, Cattochia had to be content with a member of one of the lesser branches of the Vespucci as her daughter’s betrothed. Simonetta and Marco had never met. It was a good marriage for Simonetta, in Florentine terms, where the family into which one married was more important than the appearance or the character of the bridegroom.

The beauty of Simonetta Vespucci is immortalized in this portrait by Piero di Cosimo. Though painted some years after she died, it bears her name and represents the Florentine ideal of feminine beauty which she embodied. Simonetta was twenty-two when she died. The snake around her neck is intended to symbolize her tuberculosis and perhaps also to link her with the great beauty of antiquity, Cleopatra.

Simonetta moved into one of the lesser Vespucci palaces, and could have been expected to settle down to the anonymous life of an aristocratic Florentine wife, bearing numerous children, amusing herself at the colorful processions, tournaments and receptions with which Lorenzo the Magnificent kept the pleasures mad Florentines entertained. And so she might have, had not two men fallen in love with her. The first, of her own age, Giuliano de Medici, handsome and dashing younger brother of Lorenzo, coinheritor of the incredible wealth, power, talent and wisdom of the Medici dynasty.

The second was a penniless and friendless artist, Sandro Botticelli, son of a tanner and nine years her senior. Without Simonetta’s face to glow in his pictures, Botticelli might well have remained little more than a magnificent technician like his contemporary Ghirlandaio. Without Botticelli to paint her, Simonetta might have emerged as an interesting footnote in the turbulent history of the Medici. Together, Botticelli and Simonetta immortalized each other. Today it is to the lonely and unloved Botticelli that she belongs, rather than to her husband, Marco Vespucci, or her prince-gallant , Giuliano de’ Medici.

"These are among several alleged Botticelli portraits of Simonetta Vespucci. The portrait on the left was painted whilst Simonetta was still alive in 1474.The image on the right was completed in 1480, 4 years after Simonetta's death in 1476, aged 22."

On January 28, 1475, twenty-one year old Giuliano staged a spectacular tournament in the Piazza Santa Croce. The nobility of Europe was invited . Each cavalier carried a banner on which had been painted, by such artists as Verrochio, the lady of his love. Giuliano called in Botticelli to paint the exquisite Simonetta on his banner. it was the only time she was ever painted from life. Botticelli conceived her as pallas, the fully armed goddess of wisdom. The twin climax of the pageantry game when, Giuliano, not surprisingly, was acclaimed champion of his own tournament and Simonetta was crowned Queen of Beauty to the roared approval of the entire population of Florence.

In a box of honor,sat Marco, watching his wife being honored by a Medici who was obviously in love with her. He was a quiet man, with no particular talent or ambition, working without distinction in the Vespucci wine and silk business. But he had a temper; he could grow embittered; he fought back when he thought his rights were being violated.

"That re-occurring face. What would drive an artist to repeat these features over a span of decades? Whilst crusty old Historians whine about Romantic notions not being evidence, those who have ever been touched by a real-life Muse will have all the evidence they need by simply looking. "

Was Giulano Simonetta’s lover? Vasari, bad painter but good biographer of the Renaissance artists says yes, and most have swallowed on that assumption. It appears she was chaste, there being no tidbit of evidence from the gossip loving Florentines; and she was buried in the Vespucci vault with full honors. Lorenzo, who ruled both Florence and his family, well knew the danger of outraging the wealthy and powerful Vespucci clan.

The Florentines could drive himout any time they pleased, as was demonstrated just three years after Giuliano’s tournament when he Pazzi family, prompted by Pope Sixtus IV, rose in conspiracy and stabbed the handsome Giuliano to death during a High Mass in the Duomo, almost killing Lorenzo as well. Two years after Lorenzo’s death the Florentines, disliking the arrogance of Lorenzo’s son Piero, sacked the Medici Palace and drove the family into exile.

That Giuliano was in love with Simonetta there can be no doubt, nor does his fathering of an illegitimate son, the late Pope Celement VII, permit any denial of his carnal Florentine nature. But this was also the heyday of extolling Dante’s idyllic love for Beatrice, Petrarch’s for Laura. The lusty Florentines were not averse to a poetic passion. Is it important to establish Simonetta’s character? Much as we may admire the linear beauty of Botticelli’s paintings, it is difficult to love reverentially the image of an adulteress. The purity of Simonetta is implicit in her beauty. Take away the goodness and what remains is an exquisite mask, or, changing the figure of speech, the shell on which the Venus emerges. One can long for Simonetta, but never lust for her.

Was Sandro Botticelli, who was never known to love any woman of the world, nor to be loved, perhaps projecting in paint every man’s mother image, even as Michelangelo carved her in the marble of the “Pieta” ? He was a sad and lonely man. All of his Simonettas are sad and lonely- two emotional ingredients needed for transcendental beauty.

There are prettier girls in Renaissance painting, brighter, gayer, with more surface charm, with whom one can become infatuated. Botticelli’s Simonetta appeals to the very deepest strata of man’s tragic soul, to his inescapable knowledge that death is implicit in life. All of Botticelli’s representations are authentic projections ,if not of Simonetta as she saw herself in the mirror, then of Botticelli who saw her mirrored in the eyes of his own longing. Who is to say that an intuitive painter does not see a woman more clearly and penetratingly than she sees herself?

There is no true historical Simonetta. She is the eternal feminine, Venus rising from the blue waters of the Mediterranean. This is why she is immortal.

David Bellingham: “Her sexually charged appearance, however, is somewhat paradoxical: on the one hand she is represented as the marginalised object of the male gaze in a culture which privileges the male as both producer and consumer of art; on the other hand she is a goddess, deeply rooted in western civilization, who empowers the female.

This ambiguous identity is what has made Venus so alluring over the years, and a subject particularly suited to the Neoplatonist agenda followed by the Medici in Renaissance Florence. Sandro Botticelli (c.1445-1510) incorporated her into three of his most famous masterpieces, beginning with the “Primavera” (c. 1482) and “The Birth of Venus” (c. 1484-6), and culminating in the “Venus and Mars,” now part of the permanent collection at the National Gallery, London (Pl. 1). An essential feature of Neoplatonist teaching was its reading of texts on a number of different levels, embracing both the pagan and Christian belief systems.

As the famed art historian, Ernst Gombrich (1909-2001), once proclaimed: “To them *the Florentine Neoplatonists] the myths were not only a mine of edifying metaphors. They were in fact yet another form of revelation. . . . The pagan lore properly understood could only point towards the same truth which God had made manifest through the Scriptures.”