Charlie Chaplin represented a vision of laughter, of comedy, that tore away at the veil, a social burka fitted over its explosive and unpredictable composition.A contrast of fast nickelodeons and the slow dimes of higher culture. He enabled a reconnection to a repressed tradition of vulgar art and a return to the bad and bawdy; a world of animality, obscene, sexual and scatalogical humor situated between the knees and the navel. Vulgar humor was embedded as central to Chaplin’s vision:

At supper that night, as many times before, his father said, “Well ’spose we go to the pictures show.” “Oh Jay!” his mother said. “That horrid little man!” “What’s wrong with him?” his father asked, not because he didn’t know what she would say, but so she would say it. “He’s so nasty!” she said, as she always did. “So vulgar! With his nasty little cane; hooking up skirts and things, and that nasty little walk!” ( James Agee, A Death in the Family )

The nasty little walk, was also a metaphor for the moloch of moolah that became inevitable with the industrialization of the movie industry. What Walter Benjamin would term the ”mechanical aura” of culture, could create a mass audience of heretofore unheard of and uncharted dimensions, raking in revenues that were not previously imaginable through what economically would be termed the economies of scale.

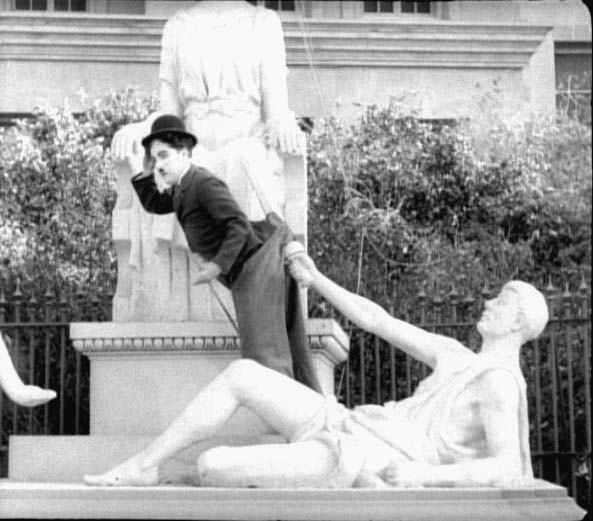

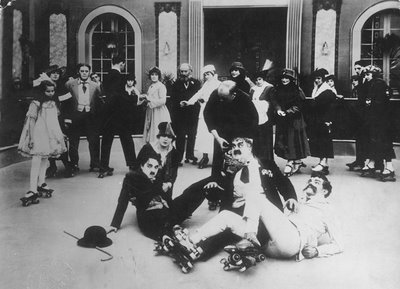

”From the romantic period on , the notion of the artist has been cultivated as someone in opposition to the dominant mores of society and certainly opposed to monetary motive by the nobility of his or her calling. In this context, the very profitability of mass art forms has in itself probably been sufficient to render them suspect to guardians of culture.” ( William Paul ) The ability to record performance, and reproduce it, transformed previous performance arts from transitory and fleeting into commodity fetish. Art as performance, as a pacification of the masses has had a long run at the playhouse; from spectacles of the Golden Calf behind Moses’s back through Aristophanes and even public hangings and executions; all had contributed to sate any appetite with their generous portions of vulgarities and obscenities. A form of ”grotesque realism” from which Chaplin’s films derive from, directly appropriating the coda and hooks from the dance halls, illicit gambling dens and burlesque theatre of London in the Edwardian age. A market place that reflects the alter-ego of official culture, supported by the people for the people, and this sense constitutionally a tool for freedom.

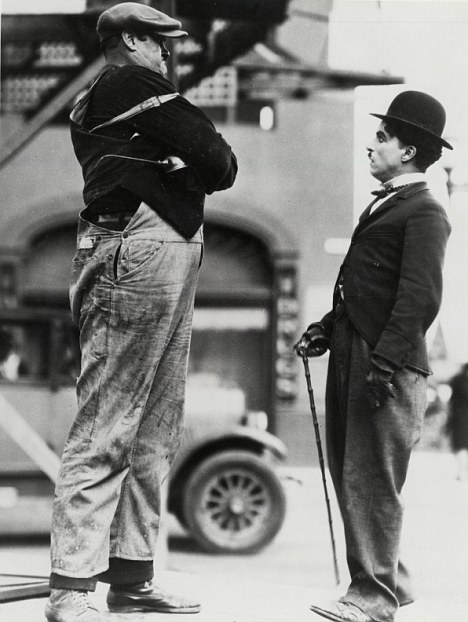

”This opening ….defamiliarizes a figure so recognizable he need not be named. Seen through the distortion of nostalgia we are unlikely initially to recognize Charlie Chaplin in the horrid, nasty, vulgar little man. But indeed that was how Chaplin was received initially by guardians of culture, suspicious of vulgar slapstick, with its too-fast action, its love of speed and violence and its hatred of authority and propriety. Chaplin’s behavior flaunted social inhibitions, provoking censure or laughter depending on your point of view. But, as Rufus’ mother indicates, it wasn’t simply what Chaplin did that made him nasty but his physical being – not just hooking up skirts, but “that nasty little walk!’ ” ( Tom Gunning )

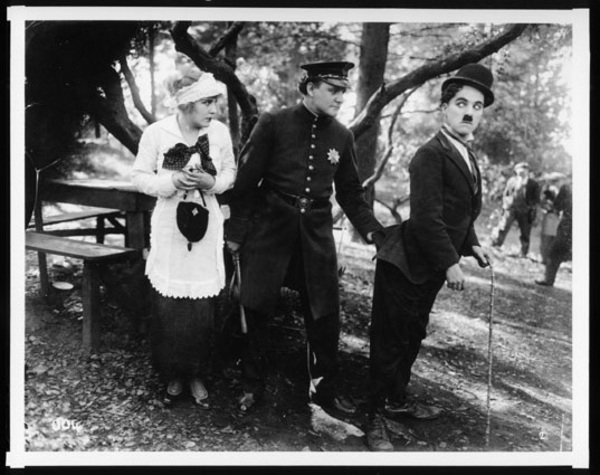

Chaplin challenged the axiom that civilization is built on repression, and this valorization and active promotion of the ascendency of the body was dangerous in this respect in its disregard or inversion of the Freudian foundations in Western ideology. Freud’s syntheses proposed the physical drives of the body as primary and fundamental with the demands of the libido acting as motor of existence. However Chaplin’s artistic drive ran counter to the notion of a libido destined, doomed and marooned to disappoint, thus necessitating a repression under risk of emotional anarchy.

Indeed, Chaplins physical humor recalls a spontaneous approach to comedy, rooted in the burlesque and traveling carnival , and geared to the ”natural man” whose urges and bodily needs, both of generation, and excretion outweigh the demands of society and his own personal responses at an awkward attempt of self-dignity. This club tradition is ”downtown” as opposed to the ”uptown” ideal of the body as non-central to bourgeois individualism.”cosmetically enclosed and complete onto itself, never openly emitting noises, smells or embarrassment. Chaplin’s bodily humor was the “nasty” Chaplin, rather than the sentimental Chaplin, that cliché that so many critics use to avoid dealing with Chaplin’s actual complexity.” Think Woody Allen as opposed to Neil Simon. The high arts then, could only be accomplished, in fact, owed their existence to the repr

on of the low, rendering them, in turn, culturally suspect in the eyes of the non-elite.” In a sense they are dangerous to the ways we think of ourselves as civilized peoples. But the elevation of the high is accomplished …although the very value we want to accord the high has generally necessitated denying the costs. Our claims to nobility as human beings, that which sets us apart from beasts, is built on a repression of what connects us to beasts”. ( William Paul ) In fact, There is an ongoing paranoia, a dread that high culture will be corrupted if new cultural manifestations will be permitted to enter the gene pool- even in the shallow end, ”no jews, negroes and dogs” could be permitted to question the dominance of the mentality of precious object in a gilted frame that separated the cultures through monetary exclusiveness.

The fast nickels and slow dimes analogy between popular and private. When low culture becomes of interest to the world of high art, something inevitably gets repressed in a process of dilution and homogenization in an effort to kill the active bacteria: ”Bakhtin sees a reduced form of laughter taking hold of official culture from the romantic period onward: Laughter was cut down to cold humor, irony, sarcasm. It ceased to be joyful and triumphant hilarity. Its positive regenerating power was reduced to a minimum.”

The dynamic is often one of evoked sentimentality transforming itself into the excessively physical; crying and sobbing take on ”urinary forces” . An uncontrolled, explosive body will not let itself be restrained by the dictates of the higher classes. A body, in short, is to be seen and heard. The modernist tendency was to transform, socially manage the volatile and radical , forces of the grotesque, ehich have no clearly predetermined targets, into its more neutered and muted forms, principally satire which was deemed to have more acceptable benefits to society. Satire, with its corrective function could keep the Freudian edifice intact since laughter could be a commodity; a product with a function and utility.

”Chaplin’s natural “body in process” provokes laughter because of his violation of social taboo, breaching the codes of repression that had been imposed with the growth of middle class propriety in bourgeois culture. Thus even this “natural” body, this return to the clowns of carnival, has a modernist dimension, one closely related to the modern preoccupation with portraying the physical body in its grotesque, rather than idealized or eroticized, forms, an impulse evident in key modern works by Degas, Schiele and Picasso, among others.” Chaplin in Modern Times behaved like a machine.An automaton, caught in the wheels of ”progress”, a beautiful, graceful yet expedient piece of equipment. The grotesque motions, jerkiness and jarring rhythms was not the movement of an organic whole, but that of a fragile, disconnected series of moving parts.

”As far as I know, no one has ever thought to praise him for the anality of his humor. A point that touches on this might be mentioned in passing but always in a way that ends up containing it; this aspect of Chaplin,s humor is simply not regarded as fit for praise, certainly not to be made central to his art. In effect there is a kind of censoring here of the lower body stratum. This censoring represents an astonishing distortion of his films.” ( William Paul )

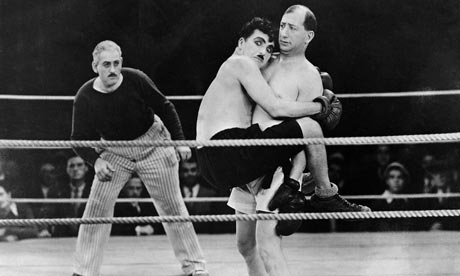

Chaplin’s ”vulgar” humor is more that an artifice of titilation in his films. This humor informs and forms most of his work until WWII. through well articulated and complex presentations of sexual imagery. In social terms, Chaplin with his ragged upper class costume, his cane swinging like a phallus, has little doubt about his social superiority. The narrative of sexual innuendo is central; anxiety centered on exposure, an act he both desires, by subtle forms of initiation, yet fears and dreads. These are not incidental details and preclude any importance to his canonized humanness and sentimentality to which dominant critical standards have elevated on the one part, and reduced the base humor to satirical analysis by meddling in social class theory so there is a detour from eroticism and the belly to the cerebral cortex. This despite, evidence that some scenes suggest, quite graphically, scenes that eroticize same sex contexts that endow the Tramp with a surprising aggressive power in the face of other males who are always physically more imposing for example, such as with the millionaire and boxer in City Lights.

William Paul’s “Charles Chaplin and the Annalsof Anality” argues that previous critics have ignored the “vulgar humor” that is “central to Chaplin’s vision” , failing to emphasize “the raucously insistent lover body imagery” of his work. Replacing such imagery in what he takes to be its properly privileged place, Paul finds that the key questions raised by Chaplin’s work are “How can upper and lower body be made whole? The answer, or its attempt at resolution passed through what Frederic Jameson termed the ”psuedo-couple”, an illusion that served as a structural device for preserving a sense of narrative within, as in Chaplin’s film, a flimsy pretense of a plot or story line.

” The pseudo-couple is the ‘unstable, acrobatic resolution’ of the need to keep narrative going. That the resolution is unstable and yet acrobatic would, of course, suit Chaplin perfectly. What I would take from Jameson’s account is the sense of the pseudo-couple as a stimulus to new and in essence contrary formal energies. The pas-de-deux does not constitute an obstacle to narrative as such. It constitutes, rather, a counter-narrative, a story told about something else altogether. Modernist writers, from Flaubert to Beckett, found that they needed to tell that story. So, I think, did Chaplin. ( David Trotter )

The ”faux-couple” pretense could simply serve as point of departure in an articulation between the vulgarity of the grossly material world and the elevated quality of the more spiritual, at times sentimental impulses implicit in Chaplin’s treatment of character; a form of duality suited to the anti-hero tramp and his anxieties and torments which could be presented as abstract stylizations from which to project sexual imagery, and the interlocking themes of sight,gaze,and blindness placed within potentially disempowering contexts that are detached and liberated from the constraints of the plot. But rarely, is there any firm basis, even resolve for authentic relationships ; these are sacrificed to durable co-presence instead.

”The most nearly Rabelaisian of Charlie’s pseudo-couplings occurs, to brilliant effect, in Police (1916), officially the last film Chaplin made for Essanay. The film’s celebrated flophouse scene pales by comparison with the muscle-taking-root episode which follows it. Charlie has been thrown out of the flophouse because he has no money, and is mugged in a dark alley in a manner verging on the orgiastic. He and the mugger ransack each other’s persons in what appears to be full mutual knowledge and consent. The mugger rummages through Charlie’s rear trouser-pockets a second time, even after he has discovered that they are empty, a manoeuvre which Charlie interprets as sexual. In this case, the mutual rummaging has re-united a pseudo-couple: the pair were cell-mates in prison; they go on to rob a house together.

”… enact imitation, as Charlie’s body conforms itself to a machine, or to someone else’s expectations; and both kinds of scene comment upon imitation, through sheer excess, and the pleasure taken in excess. Both kinds tell a story. Slapstick comedy reproduces in fantasy the insult the body suffers in the world. By contrast, Chaplin’s tramp comedy insists, as Mark Winokur has pointed out, on the intelligence of the body in avoiding insult (or at least terminal insult) through self-transformation. It seems to me, however, that the intelligence at work in tramp comedy amounts to something more than avoidance, something less than self-transformation. It is that something — at once enactment and critique of imitation.” ( Trotter )

Slapstick, a genre that relies primarily on the artist’s body, undermines traditional conceptions of heroic masculinity by enthroning a beleaguered, victimized character as the hero of the day according to Adorno. This, in addition to his suggestion that art fails in its commitment because it cannot produce accurate representation. Thus, the body as commodity and the generic constraints of satire could for example, never project the horror of nazism in The Great Dictator, since the transfer of body language from one of Chaplin’s characters to another could only invoke sympathy. But the theme of alienation and disconnect can be seen through the prism of different aesthetic, perhaps unforeseen:

”For modernist artists and critics like Brecht, Kracauer, Benjamin and Epstein, as well as Leger, Chaplin offered perhaps first mechanical ballet; a synthesis in which the hard-edged rhythms of the machine had become part of the human sensorium.” This industrial processes, which were seen to liberate people, actually created a performance aesthetic, and in Chaplin’s case, a platform for balletic improvisation on the precipice of disaster. ”Instead, Chaplin balletic – acrobatic-mechanical physical process seem to remain divorced from achieving anything (not that he doesn’t try…) Thus Chaplin’s modern body remains unchanneled, oddly purposeless, filled with a nervous energy that discharges itself without effect (or rather, often with counter effect).” But then Chaplin’s Tramp was a marginal, a vagrant, already unsuited and obsolete in the era of modern machine, and subject to all the breakdowns that arise to equipment not well maintained

The avant-gardistes saw in Chaplin, this relation with modernity as part of an anti-fascist aesthetic.For Benjamin, Chaplin personified his beloved themes of modern art as a product of detached, peripatetic observation of urban mass existence; the relation between artistic innovation, technical innovation, and capital; the dependence of art upon locality; and the revolutionary potential of art. ”Adorno objects that ‘…the idea that a reactionary individual can be transformed into a member of the avant-garde through an intimate acquaintance with the films of Chaplin,strikes me as simple romanticization…’, but as the above quotation illustrates,it is not, as Adorno assumed, the content of a film that is important for Benjamin, but film as a phenomenon in itself.

More precisely, it is the challenge that film poses to traditional concepts of art that interests Benjamin,and from this he extrapolates the theory of ‘loss of aura’ as the manifest result of mechanical reproductions of art works.” Ultimately,in Chaplin, Benjamin and others saw the power that can be exercised by those in control of art: a power which now, thanks to art’s increased accessibility via new forms of a mass enjoyment provision,has had its traditional ritual and cult form expressions altered, and its potential for appropriation by Fascism as well as by Hollywood considerably extended.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

The effort to kill or appropriate the active bacteria always yields a kind of “mirthless laughter” [Joyce:Ulysses] Hence the burden incumbent on artists always to mine the material and flesh out the laughter: this is what Chaplin is after with his intimacies, i believe.

A similar thing happens in various theaters today. Often large crowds laugh together or individuals laugh separately, but there are marked modes of laughter. I learn alot about others and myself at these times. Clearly, something is “going on” at these parts in the film, whether the filmmaker grasps it or not. It would be fun to replay Chaplin for modern audiences in a modern cineplex or whatever they call them these days.

-mason

Again, very articulate comment on your part. The art and science of laughter is indeed a serious study. I wrote about it in a previous blog with relation to Freud and Jung i think; it goes back several months, but my understanding seems broadened by peeling away a few layers on Chaplin. That metaphor of active bateria is terrific as Chaplin really liked mucking around in it.

Very cool blog Dave. Charlie Chaplin was at a theater near our place downtown LA. It’s cool.

Thanks for taking the time to respond. With Chaplin, even a blog takes on a life of its own; he is a subject much more complex, and detailed than most give him credit for. The writers I referred to in the column, ( Gunning and Trotter, seem to understand important elements that escaped the minds of the Frankfurt school ) Best,Dave