In the countryside of northern France he made a garden. And there, Claude Monet, as he grew old and his eyesight failed him, perceived and painted sunlight and water, trees and flowers, as no one ever had before. He literally followed the Catholic polemic that ” each should tend to his own garden”, first uttered as a moral understanding to the problem of heresy.In Monet’s case, perhaps a heretical case study of the nature of ”light” in art that dragged science into the realm of visual art.

Painting can be considered a healthy profession; an intellectual activity that mixes in some light manual work, that in sum constitutes a mild form of physical exercise. Some great masters seem to enjoy a better than average life expectancy. Titian lived to ninety-nine and Picasso lived into his nineties. Monet lived to be eighty-six. His life conveneiently split into two, for at age forty-three, in 1883 he settled in Giverny, on the border of Normandy and the Ile de France.

This relocation also marked a change in fortune and repostulation of public attitude and perception. The dark combative days when Monet ( 1840-1926 ) and his friends were banned and shunned by governement sponsored official culture, and their work ridiculed by critics, was now a bad dream of the past.Monet was leaving behind the legend of a youth spent defying the artistic canons of his time.Like most innovators, he had struggled to impose a style that initially appeared discordant, uncouth, and savage, only because it broke abruptly from what had preceded it. Monet ad now embarked on a process of passing from lean times to luxury and from criticism to acclaim. His painting from 1872, ”Impression Rising Sun” became the mantle for a school of painting, whom later Monet would himself chastise for banalizing the core values of what he helped initiate: ”I am an Impressionist but I seldom see my colleagues… the little chapel has become a school that opens its doors to any hack.”

The poverty of Monet’s early years was not an ordinary poverty, but a poverty within the context of a coherent group that was beginning to assert itself. Monet was constantly penniless, with little means to support his wife and child; he was constantly rescued by friends like Manet and Bazille, who had independent incomes, or he secured advances from collectors and dealers. He was able to keep painting thanks to his own pig headedness and their support. A turning point came when he met the art dealer Durand-Ruel in 1870 n London, where Monet was on cavale, sitting out the Franco-Prussian war. By 1872, Durand-Ruel purchased about seventy canvasses and put Monet in touch with wealthy private collectors like Ernest Hoschede, whom Monet later formed an attachment to his wife, Alice. In 1878 Hoschede delared bankruptcy, fled to Belgium and Monet took up with Alice and her five children after Monet lost his frail wife Camille the same year. The brood of seven children total made made a large space in the country an imperative for Monet which was feasible given Alice,s dowry, his rising acclaim, and advances from Durand-Ruel.

The villager’s of Giverny intially regarded Monet as a sort of hippie, who had brought his little commune to their community on the Seine. he was an outsider with little time for the village chit chat, and his massive, bearded figure, and bohemian ways aroused suspicion and rumor. By 1889 they realized they had a celebrity in their midst, and after a highly successful retrospective with Rodin that year, he purchased the Giverny house as well as additional land in which he built his water lilly pond. When Monet was not painting, he was working on his garden, the subject of much of his later work.

Monet composed the arrangement of his flowers as he would have the colors of his canvases. He may have had misgivings about his paintings, but to him the garden was a certified masterpiece. Every square inch was covered with an abundance of blossoms which appeared random and disorderly, but to Monet contained secret harmonies and elusive patterns. He studies seed catalogues and added new species each year. Monet used the services of five gardeners to manage his botanical creation.

”If, I can someday see M. Claude Monet’s garden, I feel sure that I shall see something thatis not so much a garden of flowers as of colours and tones, less an old-fashioned flower garden than a colour garden, so to speak, one that achieves an effect not entirely nature’s, because it was planted so that only the flowers with matching colours will bloom at thesame time, harmonized in an infinite stretch

lue or pink”.- Marcel Proust, “Splendours”. Le Figaro, June 15, 1907Monet, however, was eccentric. Life at Giverny was governed by his working habits. He rose early to take advantage of the light. Meals were regimented and precise: eleven thirt and seven. When he was painting he would not tolerate interruption. He did not want to be deterred from his pursuit of a patch of light.He was subject to exteme mood swings; jovial when work went well interspliced between days of morbidity and melancholy which served to keep his family hosthe to his temperament. There were day he stayed in bed and worked himself up into such a passion as to commit his only acts of violence; lacerating, burning or putting his large feet through his canvases.

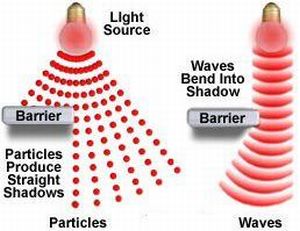

It was as if Monet in his manner as a painter and his relationship to light, was working through the same intuitions that Einstein was simultaneously developing in his particle theory of light. Where Einstein was challenging the orthodoxy of physics, Monet was conceptualizing that theory of light with paint. The established wave theory of light as electromagnetic crests and troughs gave way to Monet’s bursts and explosions of color that seemed random and arbitrary yet revealed a unified whole. To Monet as well, light did not spread ot evenly and continously through all the space accessible to it; a notion which had likely guided all art until then.

”In the face of this universally held knowledge, Einstein proposed that light was not a continuous wave, but consisted of localized particles. As Einstein wrote in the introduction to his March paper, “According to the assumption to be contemplated here, when a light ray is spreading from a point, the energy is not distributed continuously over ever-increasing spaces, but consists of a finite number of energy quanta that are localized in points in space, move without dividing, and can be absorbed or generated only as a whole.’ ”

If one looks at the ways light has been represented in art, several connections emerge between the histories of art and science. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, light was being studied by scientists and painted by artists in two quite distinct ways. James Clerk Maxwell had developed a theory of the wave-like properties of light, and in his theory unified the observed electric and magnetic field effects of light.

An argument could be made also that Monet, around the same time, was observing the fleeting characteristics of light at a certain time of day in his renowned Haystacks and Rouen Cathedral series depicting these ‘transformations of a subject’ wrought by the interaction of light and form. The way he painted light shimmering around the haystacks gives one the impression that he could almost literally see the waves: ”The mirage-like, rippling halo of light around the haystacks … is brought by Monet into the realm of the physical and material through paint and pigment. Layered, …weaving and zig-zagging in tantalising concord with the form of haystacks …yet each stroke characterised by its own quirkish irregular spark and spirit. Formed yet fuzzy, for the wave has no discreteness of edge: it achieves this ‘illusion of separateness’ through a kind of wholistic summation of smaller individual ‘wavelets’ (brushstrokes). Monet recognised this ‘inner oscillation’ or ‘jostling’ of nature, of light itself, and which he so poignantly translated with the swish and pirouette of brush.” ( W.A. Roberts )

The only thing common to the two theories is the central position held by the speed of light. What is perplexing about Einstein's theories is that, 100 years later, so few people understand them. And yet all the mathematics to demonstrate them can comfortably fit on the proverbial back of a cigarette pack.''

However, Maxwell’s ‘wave-theory of light’ was shown to be lacking, or incomplete in explaining laboratory observations in which the effects of varying the frequency and the intensity of the incoming light did not produce coherent results. There were limits on the energy levels of ejected electrons even if the scientists repeatedly increased the intensity of the light-source shining on the metal. Einstein’s prposition of ”packets” of energy, later called photons, completed the undestanding of light by explaining the anomalies: ”This was a tremendous scientific realisation of the poetic record of light as particles of discrete colour (energy) within the paintings of Seurat.Light had both wave-like properties and particle-like properties, and these ‘complementary’ aspects of light had been beautifully paralleled within the history of art, seen especially within the works of Monet and Seurat.”

”Monet had adopted Manet’s concept of painting and applied it to landscapes done outdoors.Monet was the spokesman and chief painter of the Impressionist style.Throughout his long and productive career he relied wholly on his visual perceptions. For him, especially, there were no objects such as trees, houses, or figures. Rather, there was some green here, a patch of blue there, a bit of yellow over here, and so on.The mechanics of vision were a major concern of Monet and the other Impressionists. To achieve intensity of color, pigments were not combined on the palette but laid on the canvas in primary hues so that the eye could do the mixing.A dab of yellow, for example, placed next to one of blue is perceived, from a distance, as green, a brilliant green because the eye accomplishes the optical recomposition.Further, each color leaves behind a visual sensation that is its after-image or complementary color. The after-image of red is blue-green and that of green is the color red. The adjacent placement of red and green reinforces each color through its after-image, making both red and green more brilliant. … Portable paints in the open sunlight and color perception were two components of Impressionist technique. The third component was speed.

Making natural light explode on canvas necessitated quick brushstrokes that captured a momentary impression of reflected light, a reflection that changed from minute to minute.Monet’s procedure was to paint furiously for seven or eight minutes and then move quickly to another canvas to capture a different light.”

"This dual nature of light led to the insight that all fundamental physical objects include a wave and a particle aspect, even electrons, protons and students."

For Monet, a painting was never finished, it was abandoned. Monet was completely obsessed with the degree of color and its transitions. Monet had in fact painted his wife Camille on her deathbed, still warm, in a rush of somewhat morbid inspiration, ”to such a degree that when I was at the bedside of someone I loved dearly who had died, i caught myself instinctively studying the shades of color death had imposed on that motionless face… to be sorry for me, my friend”

The genius of Monet was a chromatic imagination filled with flamboyant interpretation; the Rouen cathedral and the water lilly pond at Giverny as far from reality in its way as elongated El Greco figures are from the normal human anatomy. The pink clouds and whirls of magenta and gold in the water lily series exist only on th surface of the canvas, not in nature. Monet perhaps went further than any other impressionist of note in abandoning any pretense towards literal representation, particularly in his later work. To Monet, in general, the subject became no more than a distant starting point, increasingly ambiguous, increasingly overwhelmed by near abstract plays of color and light, which is peculiar since Monet stated goal was to capture reality with the utmost fidelity.

Monet was also part of a new tradition, that was heralded by Delacroix painting outdoors in North Africa in 1834. And painting outdoors was synonymous with painting fast, before the scene changed or light shifted. This was matched by an equal tendency to turn away from the heroic subjects and allegories that had marked the Revolution and Napoleonic rule. This era of romanic exaggeration was buried after the violent and bloody street riots in Paris in 1848. What took its stead, was a desire for scenes of daily life that reflected the developing bourgeois prosperity that was emerging. Another consideration was the arrival of the photographic arts, especially as form of portraiture. There was an impetus for impressionists to accomplish what a camera could not; namely rendering a subject through dabs of color, and concentrrte on the pigmentation.In addition, industrialization and a search for markets resulted in new consumer commodities which included paint sold in tubes, which eliminated the need to mix oil and powder, thus making outdoor painting much more practical.

The genius of Monet?How could, from close proximity to the canvas, arm’s length like Monet painted, could seemingly incoherent blurs of color transform into cathedrals and fields of flowers. The ability to imagine what a painting would look like from a distance, is beyond a technical achievement and in the realm of an almost incomprehensible personal vision.

At an advanced age of seventy-seven, Monet may have surpassed his previous achievements with his water lily panels, completed in 1921, during which his sight began to fail. In 1923, against his initial judgement,Monet was operated on to remove cataracts, no small intervention then, a time when cocaine was given as an anesthetic. The water lily panels are said to confirm the role of imagination in Monet’s rendering of nature. His declining vision begs the questions of whether he knew what colors he was using and whether the bold brushwork and iridescent light were a mere accident of partial blindness. The panels are luminous and complex in composition and finally, in the winter of his life, assured him of official recognition. However, his last paintings, done in 1922-23, were, astonishingly, a radical departure from his earlier style. These include the Japanese Bridge and Alley of Roses series.

”It is clear when one looks at these works why Chagall venerates Monet as the supreme colorist, for Chagall’s palette, his luminous pinks and blues, are all to be found in a single painting, the ”House of the Roses”. It is also clear why action painters, such as jackson Pollack, admit their debt to Monet, who stopped trying to paint ”pretty” and used thick layers of colors and slashing brushstrokes to convey an aspect of nature both untamed and alarming”.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS