When the truth is found to be lies/ and all the joy within you dies ( Somebody to Love, Jefferson Airplane )

The opening scene in A Serious Man is fictional folkloric legend where an elder man, believed to be deceased and in newly minted material form as his previous self, enters a house of a married couple in a nineteenth century European Shtetl. After a brief exchange with the wife of the man who invited the guest, she calmly stabs the elder with a large knife in the chest. He doesn’t blink or show emotion, continues on talking, before taking leave back into a blustery Polish night.Its an enigmatic encounter, and the old man may or may not be the dybbuk the wife accuses him to be. Certainly, his lack of emotion, nor the slightest wrinkling of pain would lend credence to the certainty of her actions. However, the import of the parable is cryptic and nearly inscrutable; What exactly is she stabbing? And, perhaps, the wife has had the dybbuk enter and control her instead as was often thought in legend that women were more prone to this demonic infiltration after Jewish expulsion from Spain.

The dybbuk has a long tradition.Idolatry and heresy are also important features of other biblical tales of the supernatural.The book of Deuteronomy is fi lled with examples of the supernatural in the everyday, withindividuals who commune with spirits of the dead, despite the prohibition against this action.The consequences for breaking this prohibition are dramatized later in the Bible, when King Saul, who has consulted a necromancer, a witch skilled in raising the dead, seeks to summon the spirit of the prophet Samuel. The spirit tells the anxious king that he will die on the battlefield of Mount Gilboa with his son Jonathan, exactly what happens the following day.As this story seems to imply, perhaps it’s best not to delve too deeply into supernatural matters.

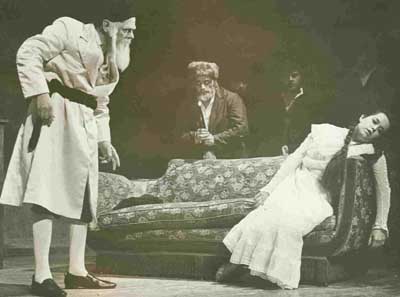

With the rise of Jewish mystical thought in the 16th and 17th centuries; a strain of which focused on the human soul and its capacity to survive beyond the body and to be reincarnated in new being came the dybbuk.Since the dybbuk is generally unwilling to leave the body,perhaps because there are other demonic forces waiting to punish it for its previous sins, it must be exorcised,usually by a noted rabbi in a complicated ceremony.

”A dybbuk (pronounced “dih-buk”) is the term for a wandering soul that attaches itself to a living person and controls that person’s behavior to accomplish a task. The word “dybbuk” is the Hebrew word for “cleaving” or “clinging,” and surprisingly, having a dybbuk is not always a bad thing for the human host. However, sometimes having a dybbuk is a very bad thing.”

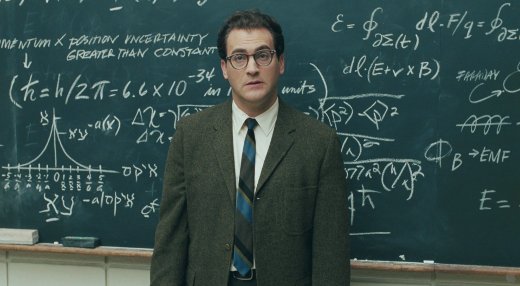

Steve Menashi asserts that the Coen Brothers dybbuk is a Jewish folkloric equivalent of Shrodinger’s Cat. And the film explores this delicate balance between the fable and the physics, the rational and the mythologic, and the ambiguities of culture and civilization; whether the destination is more important than the journey and whether the ends justify the means. Larry is the prototypical ”stiff necked” son of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob with his dogged adherence to the assumption of the universe as just. The three rabbi’s in the film, each in their own way, insist its a mystery. Einstein said that God does not play dice with the universe. But then he never succeeded in finding his unified field theory either. The Dybbuk also represents being in a state between two world, without inhabiting either one, summarizing the cultural and personal changes washing through the midwest in 1967, with the Dybbuk being symptomatic of the dislocation of the soul of the film’s characters.

”When we first meet the main character, a physics professor named Larry Gopnik, he’s writing equations on the board: “So if that’s that, then we can do this, right? Is that right? Isn’t that right? And that’s Schrodinger’s paradox, right? Is the cat dead or is the cat not dead?” Likewise, we can’t know whether Fyvush Finkel is alive or a dybbuk. We can only evaluate probabilities. When a Korean student named Clive Park complains to Larry that he shouldn’t have failed the Physics midterm because “I understand the physics. I understand the dead cat,” Larry says:

you can’t really understand the physics without understanding the math. The math tells how it really works. That’s the real thing; the stories I give you in class are just illustrative; they’re like, fables, say, to help give you a picture. An imperfect model. I mean — even I don’t understand the dead cat. The math is how it really works.”

The father of the student Clive who attempts to bribe Larry for a passing grade implore Gopnik to ”please accept mystery”.And this comes back to the fable that math and science are limited in their ability to capture reality; in many ways just complex versions of crossword puzzles, rubik cubes, chess and other intellectual pastimes. Math acts as a counter force to mystery as either a compromise position at best or merely suppressing the cauldron at its most nightmarish. At best, Math is probablility analysis based on imperfect assumptions. The proofs of uncertainty are only important in their value of plausibility as a selling tool; its not important that they be true

st that they be convincing enough so that enough of the right people believe them to be:”That’s Larry’s problem. He tries to interpret life with mathematical precision, but it’s all mere surmise. Later he has a dream where he follows elaborate mathematical equations to establish “The Uncertainty Principle. It proves we can’t ever really know what’s going on. So it shouldn’t bother you,” he tells his students. “Not being able to figure anything out. Although you will be responsible for this on the midterm.” That’s a mystery: Life doesn’t make sense, but we’re still responsible for it, even if we had no idea what we were doing. Like killing a man thinking he’s a dybbuk, if he turns out not to be.” …Of the uncertainty proof, the ghost of Sy Ableman says “Except that I know what’s going on. How do you explain? … I’ll concede that it’s subtle. It’s clever. But at the end of the day, is it convincing?” Larry: “Well, yes it’s convincing. It’s a proof. It’s mathematics.” Sy: “Excuse me, Larry. Mathematics is the art of the possible.” Larry: “I don’t think so. The art of the possible, that’s, I can’t remember, something else.”

Whether this is called politics or not, it is clearly what drive behavior and the characters psychological equations rest on more tendentious assumptions than Larry’s world. Myth, imagination, and illusion, the grand mysteries, remain at the periphery of Gopnik’s vision, under the radar of what and where he is willing to see and go, thus a sense of betrayal to himself, too difficult an idea for him to grasp and likely why the old rabbi would not want to speak to him being a truth too cosmic for Larry to even comprehend.

”The film opens with a quotation from Rashi: “Receive with simplicity everything that happens to you.” That’s Rashi’s gloss on Deuteronomy 18:13, “Be wholehearted with the Lord, your God.” To be wholehearted, “There shall not be found among you anyone who passes his son or daughter through fire, a soothsayer, a diviner of [auspicious] times, one who interprets omens, or a sorcerer … For whoever does these things is an abomination to the Lord” (18:10-12). Actually, there is a soothsayer around Larry. His brother Arthur has compiled something called “The Mentaculus,” a series of equations that form “a probability map of the universe.” Judging from Arthur’s success at cards, it actually does predict the future — but Arthur is worse off than Larry (and apparently more abominable before the Lord).There’s also, maybe, an interpreter of omens. “These are signs and tokens,” Sy tells Larry when he brings him a bottle of wine to smooth things over for stealing Larry’s wife. And Sy invites Larry to a restaurant called Embers to talk about future arrangements. (And perhaps Larry’s wife is putting the kids through a sort of fire with the divorce.)”

However, if these divinatory arts and the science of interpretation would stop, our economic and political life would have to radically transform itself or simply die without an agenda to do authentic service to humankind. Like the wife kiling Fyshkin at the film’s outset. Did she kill him because he is a bad omen, were her actions based on interpretation, and finally did the old man actually die or is he immortal, like the mystery in the film.The idea of interpretation is raised to the absurd when a dentist see Hebrew letters engraved on the inside of a gentiles teeth and begins researching this mystery in within the Kabbalah literature, a parable itself for the risks of drawing the individual into the realm of the paranormal, the occult and certain vulgarities that had their fruition in Aleister Crowley. Thus, the shamanic and metaphysical alter ego white religion is an elixir to be consumed in very small doses.

” But interpreting omens is stupid. Why look for messages on the backs of people’s teeth when their mouths can actually speak to you? Rabbi Nachtner is right when he says:The teeth, we don’t know. A sign from Hashem, don’t know. Helping others, couldn’t hurt. … We can’t know everything. … These questions that are bothering you, Larry — maybe they’re like a toothache. We feel them for a while, then they go away. … We all want the answer, But Hashem doesn’t owe us the answer, Larry. Hashem doesn’t owe us anything. The obligation runs the other way.”

Larry Gopnik’s dybbuk was the constant compulsion to do the right thing, no matter what disasters were brought about. Flunking a particularly poor student was the right thing. That it was to cause Larry “some unmerciful disaster” that “followed fast and followed faster” never entered Larry’s mind. God, the Coens seem to say, is no part of your endless troubles. You have not been punished by God. You have been punishing yourself by a mindset that does not accord with the realities of life. In fact, most of the characters are empty and amoral. The evil among these elites, as they perceive themselves to be as the ”chosen people”, is a matter of willful ignorance, passivity and blindness, rather than any deliberate cruelty. The function of religion in this environment seems more to serve as decor for consumption and is in juxtaposition as a parable of how the Jewish ethic is undermined by commerce and by extension the Judeo-Christian ethic of America.

“Our scriptures and our mystical tradition are full of ghosts — ghosts meaning the disembodied soul still wandering around. We also have teachings about what in English they call “demons,” but they’re not all evil — they’re called ‘sheydim’ in Hebrew. There are good demons and bad demons. According to our ancient tradition, demons are beings just like we are, just like animals are. They were created in the twilight of creation after the human being was created, right before the climax of creation, so that they’re neither of this world, nor of the other world, but little bit of both…. “The dybbuk is drawn to someone who is in the state where their soul and their body are not fully connected with each other because of severe melancholy, psychosis, stuff like that — where you’re not integrated. It seeks a particular person who in their current lifetime is going through what the possessing spirit went through, and so the possessing spirit is drawn to compatibility — to someone who is struggling with the same thing it did. Let’s say in my heart I have a desire to rob all convenience stores, but I don’t follow through because I don’t have the guts. The spirit of someone who has actually done it will be drawn to my desire to do it and will possess me because we’re compatible.”…

“You can tell it is real if the person is capable of speaking things that they would not otherwise be capable of knowing. Because the soul that’s in them is not integrated with them enough to be subject to time, space, and matter, they would be able to tell you things they would ordinarily not know — like what you dreamed last night, what’s happening across the street, maybe they can even speak a separate language that they’ve never known before.” If this kind of bad possession takes hold, the solution is exorcism….The point of the exorcism is to heal the person being possessed and the spirit doing the possessing. This is a stark contrast to the Catholic exorcism that is intended to drive away the offending spirit or demon. Winkler said, “We don’t drive anything out of anybody. What we want to do is to heal the soul that’s possessing and heal the person. It’s all about healing — we do the ceremony on behalf of both people.”

There was also the Jewish folkloric legend of the golem. Though stories of the golem, the word means “artificial being or“homunculus”,originated in the Talmudic times of the third or fourth century of the common era. One variation focuses on the golem’s existential dilemma. Spurred by love or some other powerful emotion, the creature realizes the gulf between itself and humans; depressed, angry, or insane,it turns on its creator. In just about every version of the story, however, humans triumph;The golem is put back to sleep, usually by erasing the divine name or mystical word on its forehead, to await its call once more when the Jewish people are in need.

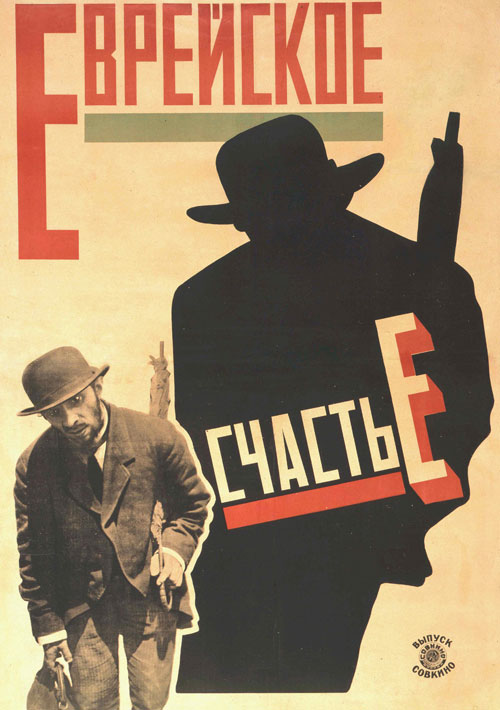

One of the best known writers of the supernatural Jewish story is Isaac Bashevis Singer. His Satan in Goray is set in the year 1666, almost two decades after Cossack pogroms devastated Jewish Eastern Europe physically and psychologically. Jews of the time believed such suffering and death could not be meaningless. It must have been part of God’s greater plan, the beginning of the process leading inevitably and inexorably to the coming of the Messiah. And so, later that year, when a man named Sabbatai Zevi declared himself the Messiah, a good part of the Jewish world simply lost its head in an ecstatic frenzy.Singer was clearly fascinated by what Charles Mackay called “the extraordinary madness of crowds,” and the ways in which religious belief, hope, and the human propensity for selfdeception combined to create a set of behaviors that were irrational in the extreme. But while

Singer grounds his tale in historical fact, he sets the story in the semi-mythic town of Goray,“at the foot of the hills beyond the end of the world.” Over the course of the novel, the generally righteous citizens of Goray, fallen under the spell of Sabbatai Zevi, are transformed into creatures both economically and morally bankrupt. This fantasy—or delirium—is so powerful that it maintains its hold on some townspeople even after Sabbatai Zevi converts to Isalm. Near the end of the novel, Rechele is possessed by a dybbuk and believes herself to be impregnated by Satan. It is part of Singer’s achievement that we are able to read the story both as a psychologically masterful display of a hysteric’s descent into mental illness and as a fantastic evocation of the figure of the possessed.

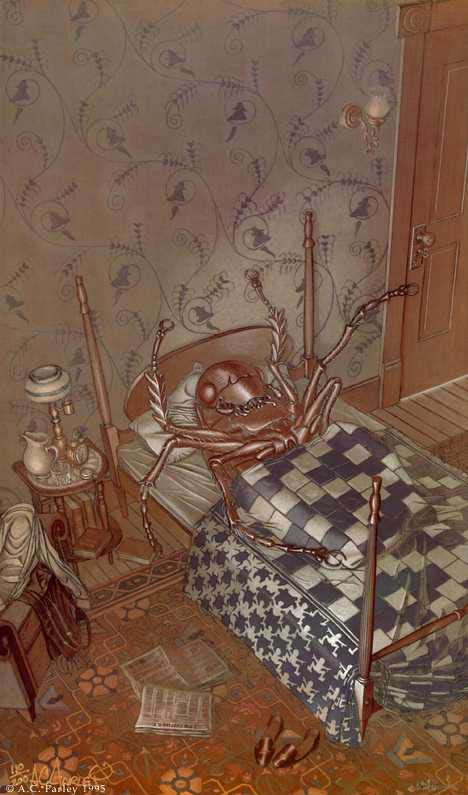

In Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, Samsa wakes from a night of uneasy dreams to find himself transformed into a monstrous beetlelike ”vermin” which much self-loathing and hatred of his changed body.Ultimately, this Jewish monster may be a creature of the modern Jewish imagination in a more fundamental way. Gregor Samsa eludes any firm interpretation. This is not to say that some answer to the question haunting any reader of serious literature,what is this about?, is absent. Kafka, instead, combines the skeptic and the believer, giving us the sense of that answer’s possibility, but not how to reach it. In this sense, we live perhaps more in the Age of Kafka than the Age of Freud since Freud insisted on the absolute explicability of uneasy dreams, whereas Kafka reminds us that interpretation leads to a world of even greater mystery.

There is also a positive aspect to a dybbuk. Sometimes a spirit will come to a person in a time of need to help. Winkler said, “The second kind of possession is called ‘sod ha’ibbur,’ which is Hebrew for ‘mystery impregnation.’ This kind of possession is a good possession — it’s a spirit guide. The spirit of someone who has struggled and overcome what you have struggled with and can’t overcome will be lent to you from the spirit world to possess you, encourage you, and help you overcome what you have not been able to overcome and what it has been able to in its lifetime. Then when it’s done and you’ve managed to achieve what you need to achieve in your life, it leaves you. Sometimes people reach high pinnacles of achievement and they fall into deep depression, and that’s explained as the loss of that spirit. So there’s a sense of loss, and it’s misinterpreted as depression. If the person realizes that, they can be thankful that they had a spirit guide to help them, and they need to continue to lift up their own spirit.”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Hmmm. I was not aware that sheydim were not all “bad, ” as it were. My impression is the agency of sheydim is limited as is that of malakim (sp?). I speculate now, that tho the former may “be” beneath the moon and the later may not “be” under the sun, there is little resembling what humans would consider good or bad about them. True enough, we imagine singing the praise of the creator is preferable to facilitating the folly of the created, but sometimes we we might find ourselves inspired to curse or accuse the creator or disposed to avail ourselves of some chance fortune the benefit of which we may not be altogether entitled.

They mystery can be accepted or rejected, but with a sublime and (hence the most gentle) irony the mystery still abides. Without an appreciation for this, Kafka can fail to please. But this is easily remedied if Kafka or the Coen Brothers or a friend or good luck manages to inspire one with the possibility that instruction has a sweetness.

Did Longinus ever suggested that pleasure might not always consist in – – my mind empties. Aristotle certainly has his objections to pleasure, but if i’m right Socrates would help me with my blankness and find a word suitable for the science of knowing and sharing of transitive value of representation or art.

Someone must have captured the sweetness of this. I vaguely recall Umberto Eco’s Name of the Rose came near.

“Abide with Me” Thelonius Monk comes to my mind. For years I haven’t even botheres to look up the words to this tune. The title and the tune suffice. The harmonies are a palpable two-way street. It is a request and a prayer. A promise and a possibility. It is, above all, very intimate.

i am too tired to invoke anythings else and must retire.

Best, mason

Funny, about Thelonius Monk. there is a new biography of him that was just released. As usual. Wonderful comments. The intro to serious man was, unfortunately, yanked off You Tube for copyright infringment. I like the ”gentle irony of the mystery” I have had Eco’s ”Foucaults Pendelum” in my notebook for a month now, toying with that literature and its relation to mystery amog some other things. Best,

Dave