During the century that followed Jacques Louis David’s death, three forces struggled for position in French art; classicism, romanticism, and realism. But their initial struggle took place in the art of David. His heroic style, suppressing passion beneath a hard chilly surface, made him the artistic dictator of Europe. Louis XVI, Robespierre, and Bonaparte were united in admiration of David. He emerges from most biographies as one of the least sympathetic personalities in the history of art, an impression not mitigated, for most people, by his painting, which they find as hard and chilling as the man.Such judgment is somewhat superficial, as there is endless fascination under a layer of iciness.

David may have been the first painter to be considered a legitimate war criminal.He was active in numerous agencies during the reign of terror and was president of the Jacobin club. He developed and refined visual art in the service of state terror and propaganda. However, it was David’s considerable gifts of image and emotionality that gave him credibility with the new revolutionary government, and allowed him to expand his gifts to one of the highest forms of artistic propaganda in the era. It was with David that success in combining art and politics became exceptional, enhanced by his own fanatical devotion and radical implication to the Revolution. While other artists of the time were painting more traditional subjects, landscapes, and the like, David made sure that he did not ignore the substantial politicality of the era.

However, the fact remains that he voted for the execution of Louis XVI and historians have identified more than three hundred victims for whom David signed execution orders.The writings of Marquis de Condorcet, and his drafting of a constitution had eloquently expressed the concept of liberty, but he did not foresee a surfeit of freedom leading to new forms of tyranny and oligarchical rule that lay ahead. Condorcet’s ”Esquisse” embodied the age of enlightenment and rationalism and visioned a just society based on scientific knowledge. David sided with the more reactionary and extreme Montagnards. Yet, by the end of his life in exile in Belgium, David,the former ardent believer completed paintings of a haunting beauty and powerful expression of psychology and emotion; a melting of the glacial sheen. His narrative, both artistic and personal, has many facets.

The age itself, however, must be looked upon as a product of the Enlightenment, in which more and more of both the intellectual and common classes were debating the manner by which people should exist within the world system itself. The Frenchman Rousseau proclaimed that “everything depended fundamentally on politics,” yet failed to consider that before political paradigms could exists, the phenomenology within the social and artistic life of the country must take primacy.

David. Oath of Horatii. 1784. 3m high by 4m wide. One of the last official commissions of the ancien regime and a revolutionary departure in style.

Though tradition has made him the archetype of the classicist who reduced antiquity to a kind of sterile purity, David is really only a psuedo-classicist whose variation of the formula was dominated by a combination of staggering realism and true romanticism. In his most frigid paintings and obsessive sensuality lies just beneath the surface. His nudes are at once adaptations of the idealized bodies of antique sculpture, carefully analyzed anatomical studies, and declarations of the allure of human nakedness that on occasion can amount to a revelation of concupiscence.

David may have been a lustful man beneath his aesthetic puritanism, but he never thought of his idealized forms as a transmutation of sensual experience, as the original forms were with the Greeks. Only in an occasional portrait of a member of his family or a very close friend does he allow himself even a confession of tenderness. But, his portraits are brilliant renderings of surface that become by second nature revelations of the personality of the sitter.

David’s immaculate surface, the often enamel like finish of his paintings, conceals preliminary stages that were as fresh and sensitive as the best rococo painting that he abominated. David’s last painting, of Mars and Venus, a love scene painted by an old man, is closer in spirit to his first master, Boucher, than to the rationalism into which he forced himself. One portrait of Napoleon on horseback, ”Napoleon Crossing the St. Bernard Pass” is so full of wind and storm, with flying draperies and a rearing, wild eyed steed, that it has become accepted among scholars as a proto-romantic conception.

David. The Lictors Bringing to Brutus the Bodies of his Sons. The painting was exhibited in 1789,after the fall of the Bastille, and the message that it imparted was not lost on its viewers.

David began his career as a protege of the state under Louis XVI, continued it as a powerful figure in the Revolutionary government, went on from there to become the grand old man of French painting as a favorite of Napoleon’s, and in the process redirected the course of French art at just the time when Paris was emerging as the art center of Europe. Something of a

tical chameleon, he holds a record for adaptive longevity under hazardous circumstances.In 1774, David won the Prix de Rome, after failing for a number of years and being highly embittered by the process. In 1772, at the low point of his life, David attempted suicide by means appropriate to a painter who was to establish a new stoic style. He locked himself in his room and resolved to starve to death. When he did not appear for several days, his fellow students broke in and rescued him.In Rome, He began immediately by puzzling and disappointing his sponsors back in Paris by sending works that rejected the airiness and freshness of the rococo style, a first declaration of independence from the society that had rejected David for so long.

It was classical Rome that most fascinated him. His rejection of rococo artifice inspired him to a vision of heroic grandeur. This was not the opulent Rome of the Empire but Republican Rome with its severe moral code and its masculinity in utter contrast to the frills and laces of the regime in France. Even the classical revival that was underway at home, with the style now called Louis XVI, could be more appropriately called Marie Antoinette, since it was a style of extreme delicacy in which classical motifs were adapted to the ideals of the boudoir and the drawing room.

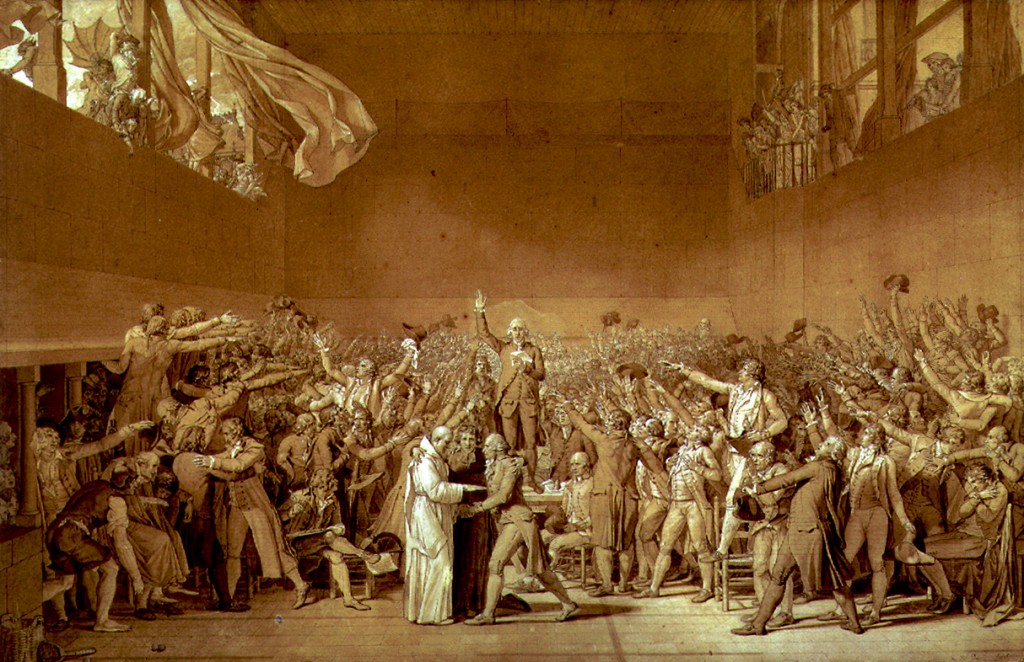

David, Oath of the Tennis Court.1789. David's painting was never completed. A wildly romanticized drawing with Robespierre, not known to be demonstrative,striking a dramatic attitude with two hands on his breast as if he had two hearts beating for liberty.

When David returned to Paris, he had not yet achieved the style of heroic severity that was to set him in opposition to the Academy’s standards. His classicism was closely relatable to that of Poussin, an Academy god, and David also proved himself a supreme draftsman in the Academy’s tradition of the studio nude. There was as yet no indication that the Academy was nurturing a murderous rebel. In his personal life, David was also following the normal course proper for an ambitious young man, by marrying, in 1782, Marguerite Charlotte Pecoul, the daughter of a wealthy contractor. By 1784 David was well set. He had a rich wife and a brilliant success in the Salon with a picture called ”Andromarche by the Body of Hector”, which brough him election to the Academy.

Comte d’Angiviller commissioned David for a painting that would raise the artist from the position of successful artist to that of sensational innovator. D’Angiviller wanted a painting of the Oath of the Horatii, based on a sketch David had done while watching a performance of Corneille’s Horace. As David developed the idea however, he worked out a composition that was not taken from any of the play’s tableaux. Helped by his father-in-law providing money, David returned to Rome to work on the painting, not as an aging student, but as an established painter. He returned as the leader of a revolution in painting and was also declared a prophet of a revolution in government.

”The Oath of the Horatii” fulfilled David’s classical ideal. The elements of the picture had been stripped down to the minimum; the brush was kept under rigid control and there was not a flourish, not a squiggle of paint to mar the icy impersonality of its execution. The drawing was hard as stone. All fluidity, all spontaneity, all feminine elegance, had given way to a determined philosophical masculinity. The grieving women, who see their sons or husbands perhaps going to their deaths, are given a secondary place, subjugated to the tableau of father and sons dedicated to the honor of country.

It was the style of the painting that created the sensation. In comparison with the sweet graces of the current fashion it was as revolutionary as cubism would be in the twentieth century. The Oath of the Horatii was exhibited in the Salon of 1785, and was interpreted not as a mere retelling of Corneille’s theme but as an allegorical comment on the turmoil that was building up to revolution. It was time, the picture seemed to say, that France save herself from the degeneracy of the old regime by returning to the ideals of firm republicanism, no matter what sacrifices might be entailed. The picture had been given an unfavorable position in the Salon, no doubt because it challenged the accepted style of the Academy, but the furor was so great that it was rehung as the center of the show.

The Revolution finally broke in 1789, as David was working on another exhibition picture illustrating a classical subject. Again, David was credited with Revolutionary sentiments in disguise, this time making Brutus the symbol of all Frenchmen who will make any personal sacrifice to protect French liberty. The particular targets were supposed to be the emigres who had fled France in the crisis, with as much of their property as possible.

Self Portrait.1794.Under house arrest after the Fall of Robespierre:''On the moral plane, we can read the painter's character in his own rendition: willful, reserved, passionate, and agitated. We need only to look at him to understand why he threw himself into the Revolution with such fervor; above all, we understand--and this may be the most interesting psychological aspect of the work--how David was simultaneously a portraitist and a history painter. His scrutinizing gaze flashes with both acumen and eagerness. He had the gift of seeing more intensely than other people; he has an inquisitive air about him. He tried to make his rendering more forceful--his fingers tightly clasped around the brush and palette are an involuntary admission. Finally, an almost fierce passion can be seen in his gaze, the passion to penetrate reality, to discover its meaning and purpose. The portraitist wanted to grasp the core of human nature, the history painter wanted to give it an ideal form.''

Early in the Revolution David supported Robespierre and the Jacobins and for the next five years he was not only ”the” artist of the Revolution, but a political figure as well. In 1792, he was elected a deputy in the convention and a member of the art commission, which made him the virtual art dictator of France. Drastic reforms were made.David abolished the Academy, along with all the secondary organizations that had trained craftsmen throughout the provinces. Whatever else the Academy had done, it had always preserved the technical traditions inherited from the old masters, and this mass abolition was a blow that affected French art from that time on. Similar to the Russian reforms after their revolution, the function of art would be to glorify the new ideals of the state and to record its triumphs, and the state would purchase these patriotic pictures from open competitions.

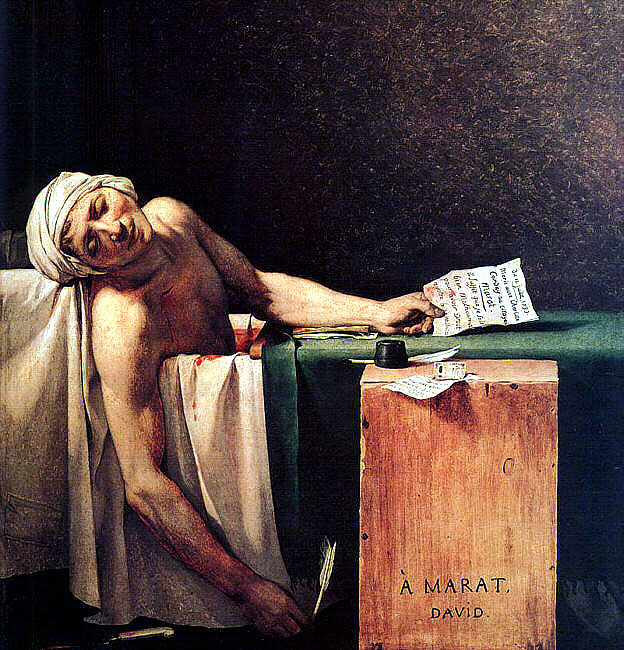

This new Commune of the Arts reigned for not quite two months. It took only that long for it to fall under the same accusations of favoritism and dictatorship that had been leveled against the Academy. It was replaced by a smaller replica of itself which in 1795 gave way to the Letters and Fine Arts division of the Institute of France which became simply the old Royal Academy with a new name. He was a busy man. In addition to his administrative functions he was in charge of commerative monuments as well as popular celebrations and state funerals, which could be elaborate affairs involving, according to some of David’s plans, virtually the entire population of Paris. And meanwhile he was still the state painter. There were plenty of martyrs and something had to be done about them. David’s possible masterpiece, ”Marat Assasinated” commemorated the colleague’s murder in 1793 by Charlotte Corday.

”Marat is dying: his eyelids droop, his head weighs heavily on his shoulder, his right arm slides to the ground. His body, as painted by David, is that of a healthy man, still young. The scene inevitably calls to mind a rendering of the “Descent from the Cross.” The face is marked by suffering, but is also gentle and suffused by a growing peacefulness as the pangs of death loosen their grip. David has surrounded Marat with a number of details borrowed from his subject’s world, including the knife and Charlotte Corday’s petition, attempting to suggest through these objects both the victim’s simplicity and grandeur, and the perfidy of the assassin. The petition (“My great unhappiness gives me a right to your kindness”), the assignat Marat was preparing for some poor unfortunate (“you will give this assignat to that mother of five children whose husband died in the defense of his country”), the makeshift writing-table and the mended sheet are the means by which David discreetly bears witness to his admiration and indignation.The face, the body, and the objects are suffused with a clear light, which is softer as it falls on the victim’s features and harsher as it illuminates the assassin’s petition. David leaves the rest of his model in shadow. In this sober and subtle interplay of elements can be seen, in perfect harmony with the drawing, the blend of compassion and outrage David felt at the sight of the victim.

After Robespierre’s fall, the painting was returned to David and was rescued from obscurity only after his death. Misunderstood by the Romantics, who saw in it only a cold classicism, it was restored to a place of honor by Baudelaire, who wrote in 1846: “The drama is here, vivid in its pitiful horror. This painting is David’s masterpiece and one of the great curiosities of modern art because, by a strange feat, it has nothing trivial or vile. What is most surprising in this very unusual visual poem is that it was painted very quickly. When one thinks of the beauty of the lines, this quickness is bewildering. This is food for the strong, the triumph of spiritualism. This painting is as cruel as nature but it has the fragrance of ideals. Where is the ugliness that hallowed Death erased so quickly with the tip of his wing? Now Marat can challenge Apollo. He has been kissed by the loving lips of Death and he rests in the peace of his metamorphosis. This work contains something both poignant and tender; a soul is flying in the cold air of this room, on these cold walls, aropund this cold funerary tub.”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

I don’t know, I think “willful” may not be a strong enough word to describe the character behind that face. Love the self portrait, though. Thanks.

Thanks for reading

yes you’re right, ”willful” by itself is very incomplete. thanks for reading.

In an unpremeditated moment, David exhibits a sort of classical style depicting the phenomenon of death. There but for the grace of G-d he would seem to be saying. And all that aside, to have abolished then re-established the Academy and lived! Beautiful rendering of David, Dave!

Marat challenge Apollo? As if this death so rendered (this machine) kills fascists? It is all quite heady! But those were heady days.

I think Dick Cheney would simply skip one long mechanical beat to be rendered as Napoleon, or perhaps in a tender moment he’d have David paint Richard Nixon departing in his last helicopter of state. Can it be that hard Republican surface is at last degenerating into – (talking off the top of my head) some kind of Baconian disintegration? Where are the pure productions of America today when we need them so terribly?

I guess these simply are not heady days. Ever since Eliot quoted, “Mistah Kurtz—he dead” classicism is so passée. I am in way over my head, but have not some musicians attempted to continue work in a sort of classical vein?

Lots of stuff flying about in my head. What do you think, Dave: did modernism finish wrestling with classicism? Have post modern aspirations or postures addressed history or even successfully depicted/critisised the spirit of our time? I’ve never been sure if it really matters anymore (shame on me!), but it troubles me. I am sincere.

“The thought of what America, the thought of what America, the thought of what America would be like, if the classics had a wide circulation, why, it troubles my sleep.” If i remember his snarky tone correctly, it still troubles my sleep.

Thank You, Thank You Dave!

-mason

PS. Someone, (himself perhaps?), described Roland Barthes as a sort of structuralist rear guard. Drop me a line via email about your other site and endeavours. I’ve also formulated a possible answer to one question not yet asked in these exchanges.

I,ll have to get back on a coherent response to you this week. Except, I don’t think modernism is finished ”wrestling” with classicism. I think this is a long, almost eternal battle. They need each other.

Hi Michele,

I sense what you mean. For me this face is great source material for a fun parlour game. You can do it with a mirror or with photoshop. Make two “different” faces by doubling each side of the face.

You may not think different about the face, the style of painting or the man, but you may appreciate more about the times and the hurried rendering of Marat.

-mason