Marcel Proust’s Paris aristocracy: perpetually engaged for dinner, decorative, idle and dangerous for social climbers. In Proust’s ”Remembrance of Things Past” , what lent the aristocrats of the Faubourg Saint-Germain their luster was precisely their ”famous and poetic” names , whose poetry derived from the narrator, Marcel’s, youthful reading of Jean Froissart and other chroniclers of medieval chivalry and war. What made them seem, in the end, so wasted and frivolous was precisely the disproportion between their historic names and their lives, lives spent fretting over dinner invitations and keeping ”upstarts” out of the Jockey Club.

To underscore that contrast and make it more vivid, Proust frequently used historic French family names, with the result that the ”forebears” of many of his minor characters can actually be found in Froissart’s pages. There is for example, Proust’s Prince de Foix, whose ancestor, Gaston, figure notably in Froissart’s ”Chronicles” as the gallant knight who in 1358 rescued three hundred ladies from the clutches of the savage ”Jacquerie”, a feudal peasant uprising. The young prince, alas, is a mere snobbish man about town, ”fo whom the practice of impertinence,” says Proust, ”seemed the sole preoccupation”.

There is also the Duchess d’Auberjon, whose namesake, Guichard Auberjon, in Froissart’s ”Chronicles” was a brave Burgundian warrior who once routed a ferocious company of freebooters. Guichard’s descendent, however, is one of those nonentities who is invited to help out at parties, as if, says Proust, she were a hired waiter. Then there are the supremely highborn La Tremoilles, whose ancestor Sir Guy de Tremoille was chamberlain to a king of France and who, on the eve of an invasion of England, reports Froissart, ” had his personal ship magnificently decorated” with devices and paintings” at the cost of a small fortune. The only enterprise left the Proustian La Temoilles, however, is maintaining their unrivaled pedigree and perhaps recalling venturesome ancestors like Sir Guy.

Yet for Proust the deeper truth about the aristocrats of the Faubourg Saint-Germain did not lie in the objective contrast between their feudal names and their futile lives. It lay, rather, in recapturing how mysterious and ”irridescent” they first appeared to him and how they appeared later on, when time and intimacy had effaced the magic of their names. There was a real, and decisive contrast between the worlds of Marcel Proust and Jean Froissart. To a medieval chronicler like Froissart, the truth about men lay simply in what they did, especially in politics and war. So he went about energetically collecting stories of men’s feats and adventures. To Proust, men,s deeds meant little and revealed less. What mattered to him was recapturing the subjective aspect of men and things; how they appeared, not objectively, but in one man’s memory and consciousness.

''Marcel Proust ingested caffeine, injected adrenaline, inhaled stramonium, tobacco, and marijuana, and used narcotics in vain attempts to alleviate his asthma. Proust spent his last twelve years sequestered in his bed, writing Remembrance of Things Past, his greatest work.''

We have grown so accustomed t such subjectivity in art, in literature, and in thought that it takes a real effort to grasp that Froissart would have found such an approach quite literally incomprehensible. The passage of five centuries had wrought profound changes, not only in the fate of aristocracies, but in the very way people’s minds grasp reality.

”Remembrance of Things Past” , is a book providing a clue to the central mystery of France itself. It functions also as a work of consolation for all the mortals caught in the coil of time. The work’s great theme is the metamorphosis wrought by Time. This sense of metamorphosis, tied to Proust’s keen sense of the organic, carries into the tragic, temporal dimension Proust’s peculiar sensitivity to changing perspectives. Perspectives change in space, in the heart and in society. External reality is but a cluster of moments no two of which subtend the same angle. This is impressionism, but impressionism on the move, whether the moving object is the narrator’s life or the ”little train” to Balbec.

In 1905, Proust’s mother died, releasing him to final lonliness and earnest search for entree into his own endowment, his precocious powers of evocation. In his relativity Proust is a modern, though the modern most lavish with old fashioned virtues; characterization, ambitious scale, idealistic rapture an

ylistic confidence. Proust abolished the nagging contradiction between the author as God and the author as nebulous character, as reader’s confidant. In Proust’s cosmos, Marcel is both the most supine of witnesses and the mightiest of Creators. His perceptions are not derived from substance, they are substance.And the plot is not what connects the images and gestures and masks; their enclosure within one field of perception is the plot, the drama.

Our excitement as we traverse these four thousand pages has to do with their providential coherence: microscopically, with the dissecting delicacy of each sentence and the ecology of mutual assistance the tender images extend toward one another; and macrocosmically, with the thrilling leaps of far flung continuations and a grand architectural completeness. Like Dante, Proust lifts us to great altitude in ”Remembrance” , and like Dante, Proust lives in this one work. There is a great dropping off elsewhere.

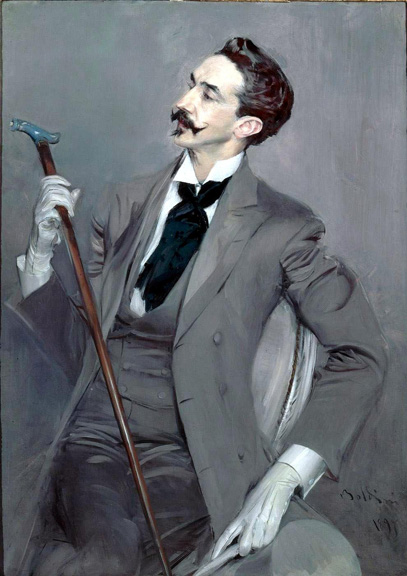

Proust is perhaps not only the greatest modern creator of characters; he is among modern authors the most amusing character, the most self-dramatizing and bizarre, whose cork lined room has become the very symbol of hypertrophied aestheticism. Here in North America, perhaps because of a zeal for practical instruction, there is a tendency to expect too much of Proust as a social critic. Satire of snobs and anatomizing of society occur, of course, and Proust was a climber in his day; but a personal obsession should not be confused with an artistic one. He writes about aristocracy, in their banality and glamour, their vanity and gallantry, because they are there: were there, in the life he has ceased to live, the life that lostness has bathed in paradisiacal colors. As soon call Proust an anti-snob as a gargoyle carver anti-devil; hatred is wallowed in an art of homage.

Proust would take the entire living population of France as a ”tresor trouve”, a paleontological imprint left by the past, a clue to the central mystery of France herself, with her cathedrals, her blossoms, her place names. As the hero, aging, discovers deceit everywhere and absurdity everywhere, only two things remain worth loving: Marcel and France, which are everything. The book is not a tract but a religious travail.

The remorseless pessimism of Proust’s disquisitions of the heart, the abyss he makes of human motives, the finality of all our little deaths, is not in itself appalling; there is a certain trust in the inevitability of morbidity. In the interminable rain of his prose there is a certain sentiment of goodness. Proust was one of those men who lost the consolations of belief but retained the attitudes and ambitions of a worshipper. For all his biochemistry, Proust emphasizes the medieval duality of body-spirit. For all the disillusion and cruelty it depicts, ”Remembrance of Things Past” is, like the Bible, a work of consolation. Proust had a strangely modest secret, a kind of Godless Golden Rule and the germinating principle of art: ” My experience in the library which I wanted to preserve was that of pleasure,but not an egotistical pleasure, or at all events it was a form of egoism which is useful to others- for all the fruitful altruisms of Nature develop an egotistical mode. ”

”Marcel Proust wants us to know that suffering is akin to feeling, and each of these qualities

is inextricable to what may be deemed “the human condition”, whatever it is in life that

makes it worthy of being recorded, or eternalized as art.

This equation, suffering = feeling, would later be proposed in an expanded, kaleidoscopic passage in his

most famous work, the first volume of Remembrance of Things Past, called “Swann’s Way,”

in which our narrator sets down to rehash the minutiae of his life, the fugue of suffering and sensations,

as unleashed in one afternoon by a tea biscuit.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

I think that is a deep story. I’ve mentioned some similar topics in my blog.

Thanks for reading