Dragon ladies and water fairies. Fish Maidens, rain mothers and other hybrid critters. Now you see them, now you don’t. These powerful shimmering phenomena of the Chinese imagination reveal themselves but briefly through mist and clouds.Watery nymphs beloved by mortal men have also figured in occidental art and literature.

Your Buoyant troops on dimpling ocean tread

Wafting the moist air from his oozy bed,

AQUATIC NYMPHS!-YOU lead with viewless march

The winged Vapours up the aerial arch,

On each broad cloud a thousand sails expand,

And steer the shadowy treasure o’er the land,

Through vernal skies the gathering drops diffuse,

Plunge in soft rains, or sink in silver dews.

( Erasmus Darwin, The Economy of Vegetation)

Dr. Erasmus Darwin, the marvel of his age, presents in these verses a poetic myth, an allegory of the formation of clouds, rain,snow,hail and dew. That he should represent the spirits of water in its multiple manifestations as female would have seemed entirely natural to the ancient Chinese. Nymphs, naiads, and Nereids, however exotic and strange, would have charmed them, and they could easily have found equivalents among their own rain mothers, mist clad maidens, and their lake and river queens.

In the ancient Far east, femininity was deeply involved in myth and in metaphysics, in poetry and in religious practice. The essence of the female was fertility, and fertility meant water. Maleness in its most perfect and concentrated form was exhibited by the blazing sun and the sky. The essential female was concentrated in the moist receptive earth, in the waters that fed its crops, and in the rainfall that derives in an unending cycle from its lakes and rivers. ”He” was the fertilizing heat; ”She” the fertile dampness.

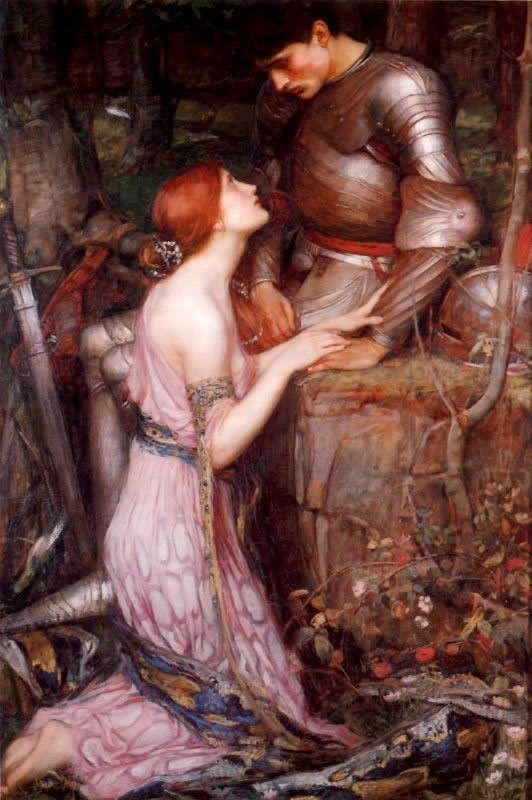

In Chinese mythology, goddesses of lakes, rivers, and seas were frequently the spirits of drowned women. Often suicides. They had, in a sense, given themselves freely to the element whose nature they shared. Now they reigned in palaces of shell and coral, attended by obsequious turtles and trains of glittering fish, to aid, it may be, men who traveled by water, or who acted benevolently to them or to their finny kin. They have a western counterpart in the maiden Sabrina, elegantly presented in Milton’s ”Comus’‘ . A suicide by drowning, the girl was borne by water nymphs to the hall of King Nereus where she underwent an immortal change.

As Chinese society became more male dominated and repressive down through the centuries, myhology sometimes provided the lady protectresses of the waters with husbands. The underwater kings were particularly evident in the north, the source of traditional male authority, while the meres and streams of the Yangtze basin in the ancient southland allowed more freedom and independence to its fishy princesses. Even when later orthodoxy assigned them fathers, husbands, or brothers as lords and protectors, these remained shadowy figures in literature; dim beside the radiant vitality of the true rulers os the water; the lvely goddesses.

All these divine women had some affinity with dragons, whose ever-changing shapes could sometimes be glimpsed in wind-torn storm clouds. The dragons of China shared nothing with the dragons of northern Europe other than the fact that they often adopted a serpentine form. The Western tradition, such as in the Wagnerian operas, of a fire breathing, odious, malignant and treasure hoarding reptilian is far removed from the Chinese rain bringing dragon who protean capabilities were endless. Indeed any water creature might prove to be a dragon- a crocodile, an alligator, a turtle or a fish. All of them have spirit power that enables them to make thunder, lightning, wind and rain.

![maclise1 ''A Scene from Undine (1843, 45x61cm; 907x1252pix, 187kb) _ detail (1186x970pix, 194kb) _ The subject is based on a moment in the romantic German novel Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué [12 Feb 1777 – 23 Jan 1843], which was first translated into English in 1818 and became almost as popular with artists in England as Goethe's Faust. The incident painted by Maclise occurs in chapter IX, where the young knight, Huldbrand, accompanies his bride, Undine, back home through the forest. The priest, Father Heilmann, who has just performed the marriage ceremony, follows behind and is visible beneath the branch of the tree. Ahead is the dark and sinister apparition, Kuhleborn, the spirit of the waters and the uncle of Undine. Huldbrand draws his sword on Kuhleborn and then strikes him, whe</p><div style=](/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/maclise1-837x1024.jpg)

on the spirit of the waters is transformed into a waterfall. ''" width="586" height="717" />

''A Scene from Undine (1843, 45x61cm; 907x1252pix, 187kb) _ detail (1186x970pix, 194kb) _ The subject is based on a moment in the romantic German novel Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué [12 Feb 1777 – 23 Jan 1843

COMMENTS

COMMENTS