The achievement of the Byzantines was to keep barbarians at bay, create a new art, preserve Western culture for a thousand years, and push a little further the limits of piety and depravity. It is only recently that the word ”Byzantium” has been freed from the contumely attached to it by generations of uncomprehending, humanist minded historians.

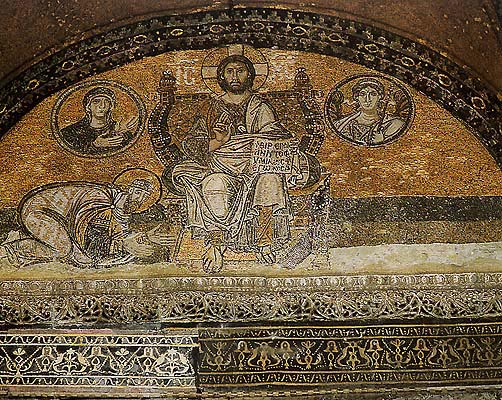

Constantine the Great humbly offers a model of the city of Constantinople to the Virgin in this detail of a tenth century mosaic in Hagia Sophia. The Emperor issued an edict of toleration for Christianity in A.D. 313, but it is a matter of historical debate whether he was ever converted to the faith.

Preeminent among them was Edward Gibbon, for whom Byzantine history was a ”tedious and uniform tale of weakness and misery in which not a single discovery was made to exalt the dignity or promote the happiness of mankind.” Christian Byzantium, or rather the triumph of Christianity itself , marked for Gibbon the end of the ”classical” civilization he so much admired, marked indeed the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. At the end of his vast work he notes modestly: ”I have described the triumph of barbarism and religion.”

Byzantine history and civilization have become legitimate objects of academic attention. As a result, Byzantine society is no longer regarded as the stagnant playground of decadent voluptuaries, immersed in sensuality and bestirring themselves only when provoked by some outburst of public spleen in the Hippodrome, or by some hair splitting theological subtlety thrown into their midst by fanatical monks. In art, literature, statesmanship, diplomacy and war, Byzantine achievements are now recognized.

''Ottoman royal architect Sinan... constructed the most effective buttress against earthquakes. Sinan first strengthened the 10 supporting walls... then added four more supporting walls. Further, he ordered workers to dig deep ditches with 50-meter distances between them, the last of which was located near the coast. Each of these ditches was then filled with sand. Akkaya said Sinan did this to prevent possible damage by a sea-based earthquake to the magnificent Hagia Sophia.''

The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead went so far as to assert that its culture was superior to that of classical Rome, and it may have afforded greater opportunities for living a civilized life than the Pax Augusta. It may no longer be a question of Romes’s decline and fall, but of Byzantium’s ascent and triumph. The Byzantium Empire was a new creation, growing out of the Roman past but essentially different from it. Indeed, it was precisely a failure of ideology in the empire of the Ceasar’s that made a new form of society imperative if Western civilization was to survive.

The credit for this survival is given to Constantine, known to history because of the magnitude of his achievements as Constantine the Great. After defeating Licinius in 323 A.D. his first task was arresting the disintegration of the Empire and of welding its heterogenous elements, both territorial and cultural, into a new coherence. His first concern was to choose a new imperial capital. Byzantium was chosen; it divided Europe from Asia, was on the main trading route to the East and would serve as a bulwark against Christianity which was rapidly gaining an ascenancy sufficient to displace the dead or dying ideologies of the ancient world.

''The current building was originally constructed as a church between A.D. 532 and 537 on the orders of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian, and was in fact the third Church of the Holy Wisdom to occupy the site (the previous two had both been destroyed by riots). It was designed by two architects, Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles. The Church contained a large collection of holy relics and featured, among other things, a 50 foot (15 m) silver iconostasis. It was the patriarchal church of the Patriarch of Constantinople and the religious focal point of the Eastern Orthodox Church for nearly 1000 years.''

For this empire Constantine the Great laid both the temporal and spiritual foundations, and in it he fused together the great political legacy of Rome, the equally great cultural legacy of the Hellenic world, and the explosive dynamism of the Christian faith. It was to last for 1,123 years, and to be governed by no less than eighty-eight effective rulers in succession.

For behind the pageant of these eleven hundred years of their history lies a deliberate and unchanging pattern, a particular vision of human life and its purposes that gives an underlying unity to the shifting scenes of the historical drama. Byzantium was above all; a Christian empire; before we can understand its unique nature, we must try to discern what meaning and relevance this fact had for the Byzantines themselves. Here we may have recourse to the image of the dome. Set over all, seeming to contain and embrace in its simple unity all the diversity and multitude that lies below it, the dome is the Byzantine architectural form par excellence. And the domes of all Byzantine domes was that of Hagia Sophia.

bers of his retinue." width="635" height="447" />

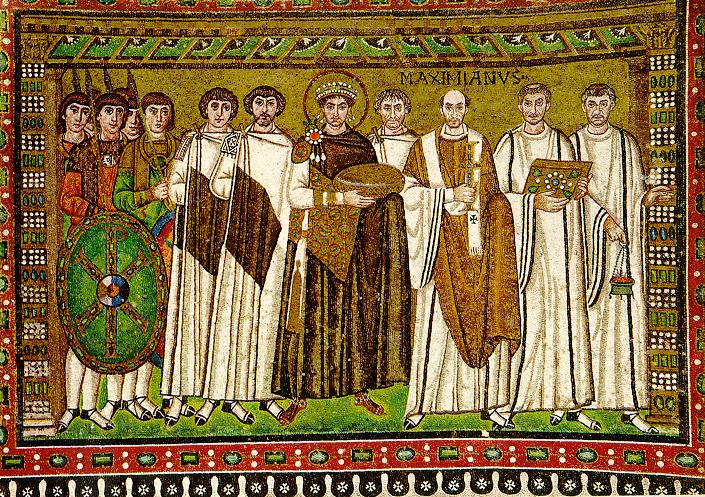

The most famous surviving Byzantine mosaics are not in ravaged Constantinople but in Ravenna, which from the sixth to the eighth century was the Byzantine capital in the West. The Emperor is carrying a votive offering and accompanied by clergy and members of his retinue.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS