Between the material and the temporal, represented in Byzantium by the emperor and the imperial body politic, and the spiritual and the eternal, represented by the saints, there is the image forming world of the soul, the world of the imagination. It is the world of Byzantine art, which not only gave expression to the divine and supernatural aspirations of man, but also to those transcendental realities which are the objects of his spiritual quest. Its sources and intent therefore coincided with those of Christianity itself, and like other forms of Christian worship its chief function was to serve the religion to which it owed its existence.

The rape of Constantinople by the fourth crusade in 1204 by nineteenth century French painter Eugene Delacroix. The central figure is Baldwin of Flanders.

The forms and figures of Byzantine art reflect that necessity. The symbolism is intelligible, clear and subtle, allowing for the intrusion of no pleasing sentiment or vacant naturalism. All is simplified, all is reduced to essentials, all subordinate to the spiritual truth which is being conveyed. To this sparse geometry of spiritual content, color gave the flesh, color employed not merely as an adjunct to the modeling but fired with an independent life. But one must also remark the subtlety of contour, the impeccable sense of proportion, the superb grasp of the whole that brought all the elaborate detail into harmony with the overriding symbolic pattern; and finally the unbridled richness of material empployed among the stones, metals,frabrics,marbles and mosaics. Having absorbed all this, one may understand something of the magnificence of this art, and of its sophisticated splendor.

The first flowering of Byzantine art begins with the foundation of Constantinople in A.D. 330 and reaches its golden age under Justinian in the sixth century. This period coincides with the final decadence of Hellenistic art which had spread across the Mediterranean and Anatolian world from Rome to Bactria; unrooted, cosmopolitan, dominated by the natural world and with the natural human form as its final measure and norm. Already, in the Near East the revival of Persia and the foundation of the Sarsanian empire in A.D. 226 had brought a reaction and a return to a more hieratic convention.

One explanation for the long persistence of the Byzantine Empire was its possession of a secret weapon ''Greek fire'', and its use anticipated the modern flame thrower. Skylitzes manuscript. John Skylitzes.

Byzantine art may be seen as the result of the imposition of Oriental forms on a Hellenistic ground. In it an almost prenatural insight into the significance of intelligible forms is fused with a lyrical sensuality that prevents stylization from becoming academic and lifeless, the mere repetition of formulas. This fusion, still incomplete in the famous Ravenna mosaics seems nonetheless to have been achieved in Justinian’s reign, if one is to judge from the astonishing mosaics in the apse of the Church of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai.

At the same time there came about the architectural fusion of early Christian basilica with the domed octagon or rotunda, a fusion crystallized in Justininian’s new church of Hagia Sophia. ”Solomon, I have surpassed thee,” Justininan is reported to have said when he first viewed the immense majesty of the completed office; and he celebrated its dedication with a banquet at which six thousand sheep, a thousand each of oxen, pigs and poultry, and a half a thousand dear were roasted for the delectation of court and populace alike.

Ravenna Mosaics. In this stiffly regal portrait of Theodora there is little to suggest her beginnings as the daughter of a bearkeeper in the Hippodrome and as the sixth century equivalent of a show girl.e

This church remains, even as the secularized museum it is today,Justininan’s most enduring monument. His attempt to reconstitute the Roman Empire proved politically a great burden. The ensuing phase of Byzantine history, opening with the reign of Heraclius in 610 and ending with that of Theodosius III in 717, was one in which the existence of the whole Empire was imperiled. Wars with Persians, Avars, Lombards and Arabs reduced the size of the Empire; from then the Byzantine Empire was centered on Constantinople and the Greek seaboard and its connections with the West grew correspondingly weaker.

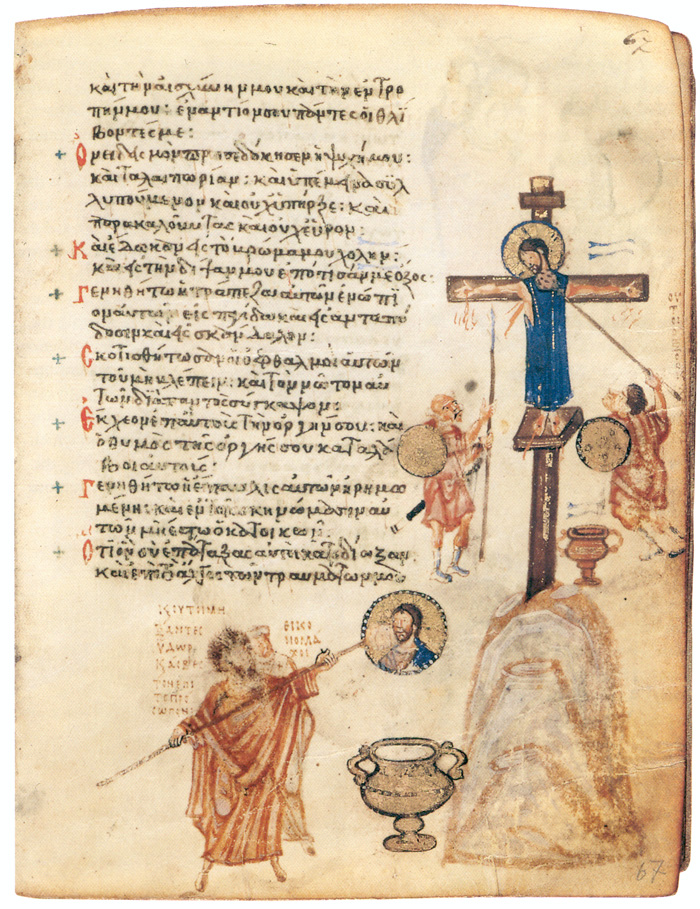

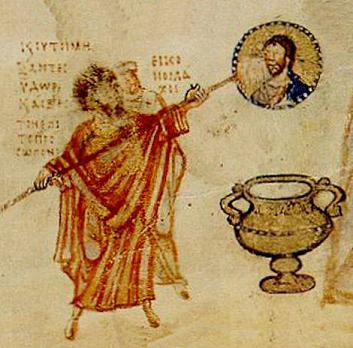

The subsequent phase in Byzantine history under emperor’s Leo and Constantine V was dominated by the field of religion; specifically, the worship of sacred images or icons, which had by this time become an integral part of orthodox Christianity. And thus when the Emperor Leo, supported by his puritanical followers from the hinterland of Asia Minor,

nched an attack on image worship in an edict of 726, reaction was immediate and intense.

The original exterior of the Hagia Sophia is buried today under a lumpish mass of buttresses, minarets, and other accretions.

Riots in the capital were soon followed by insurrection in Greece, Byzantine authority in Italy was fatally undermined, and the whole Empire was split asunder. Even the restoration of the worship of images by the empress Irene in 787 did not bring an end to the troubles. In 815, with the advent of a new emperor from Armenia, icons were once again proscribed; and it was only because most orthodox Christians, and particularly the monks, remained so intransigent in their attachment to sacred pictures that the iconoclasts, or ”image breakers”, were finally defeated.

The restoration of images after these struggles ushers in a new period of Byzantine art, which continues through the eleventh and twelfth centuries. It is a period marked by the huge patronage of such emperors as Basil I the Macedonian, whose reconquest of imperial territories at the end of the ninth century launched the Empire’s most prosperous times; Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, who as a patron of the arts has been compared to Hadrian and Lorenzo the Magnificent; and Alexius I Comnenus , whose life and character were recorded so graphically by his daughter Anna.

This was the period of Byzantine culture’s wildest diffusion. Of the profane art of the time, such as that which decorated the Great Palace at Constantinople, little or nothing remains, and our notion of it must be derived chiefly from contemporary chronicles. But of ecclesiastical art, refined and spiritualized after the attacks of the iconoclasts, memorials exist as far apart geographically as the mosaics in Santa Sophia in Kiev and the enthroned Christ at Monreale in Sicily; lying between them, in Greece, are such masterpieces as the monastery churches of Daphne, near Athens, Saint Luke in Phocis, and Nea Moni on the island of Chios.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS