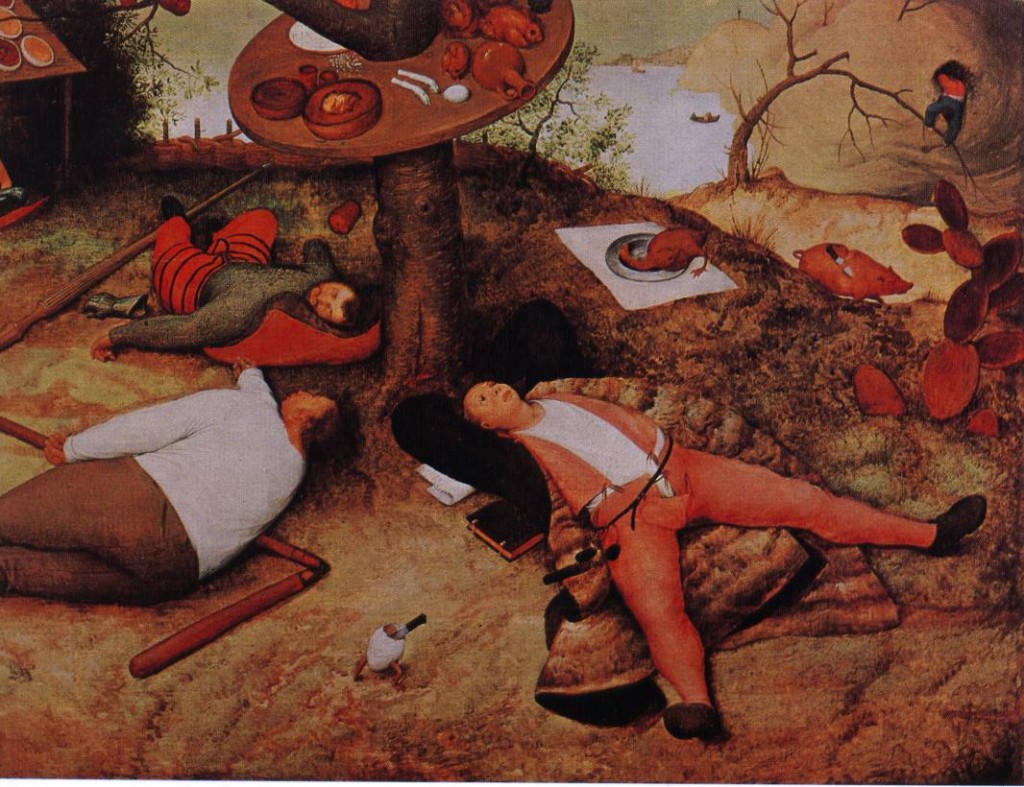

IIts the ontology of the appetite. Food as a metaphysical concept. And its consumption to the point of gluttony as an aesthetic. It is an emotionally charged symbol that dates from the Biblical Genesis and humanity’s fall from grace. Heck, it was hard to resist all the goodies at the buffet table. Morally, and artistically, there has been a lot of indigestion, fasting, and binge eating since, and understanding its personal relationship to us remains elusive.

”The moral question is . . . not, nor has it ever been: should one eat or not eat, eat this and not that, the living or the nonliving, man or animal, but since one must eat in any case and since it is and tastes good to eat, . . . how for goodness sake should one eat well (bien manger)? And what does this imply? What is eating? How is this metonymy of introjection to be regulated?” ( Jacques Derrida )

Derrida discusses the carno-phallogocentric subject , who represents the self-present, virile flesheater, a subject who thrives not only on the real sacrifice of animals but also on the symbolic cannibalistic sacrifice of other humans. This paper forms the basis for a It can be objected, that Derrida homogenizes the varieties of animality under the category of the ‘animal’ and secondly; that in order to deconstruct carno-phallogocentrism, Derrida should have adopted a vegetarian stance ,and finally that Derrida is in danger of blurring the differences between the animal and the human. In any event, humans are passionate about eating for the most part, whether we consume it, or it consumes us, and our relationship with food has evolved into a modern aesthetic.

Food was the basis of the first class system. Superior nourishment is the most primitive form of privilege. Socially differentiating cuisines, however, occurred relatively late and, until recently, were found only in some parts of the world. Originally, quantity mattered more than quality.

The gigantic appetite has normally commanded prestige in almost every society, partly as a sign of prowess and partly, perhaps, as an indulgence accessible only to wealth. Gluttony may be a sin, but it has never been classed as a crime. On the contrary, it can be socially functional. Big appetites stimulate production and generate surplus – leftovers on which lesser eaters can feed. So long as the food supply is unthreatened, eating a lot is an act of heroism and justice, similar in effect to other acts of this kind, such as fighting off enemies and propitiating the gods. It is usual to find the same sort of people engaged in all three tasks.

…”When it was finally over, when Takeru Kobayashi was finally set free, he would emerge from the Brooklyn jailhouse and utter these words. “I’m really hungry.” The only thing the slim, 32-year-old Japanese native had consumed during an incarceration that lasted something less than 24 hours was a glass of milk and a sandwich, which, according to conflicting reports in the New York press, was either bologna or peanut butter. Whatever it was, it was not the one thing Mr. Kobayashi had been craving since his arrest on July 4.”I wanted to eat hot dogs,” he said.”

''What struck me as I read this last section, is that Pollan’s approach feels remarkably Talmudic,” says Hazon’s Leah Koenig. “What else did the Rabbis do but seek to uncover existing universal truths and use them to shape a code of ethics and commandments for Jewish people to follow? (We can only hope that Pollan will end up as Hillel, and Nutritionism as Shammai.)”

John Milton in ”Paradise Lost” was one of the first to seize upon food as a foundational concept of creation, and he drew a complex distinction between the “restricted” and the “general” economies, of eating that is taste; which served as an aesthetic point of departure that encompassed social, moral and economic consequences as a defining aspect of identity. In short, a restricted economy is one in which everything circulates, and which thus entails no loss, whereas a general economy produces excesses that by definition cannot be utilized, or inscribed back into a closed cycle of circulation. The general economy, whose logic is not organized according to the typology of the mouth, allows for waste–if at the expense of taste. There is nothing tasteful about the general economy. Like a barbaric exterior, it surrounds and enables the restricted economy, whose very coherence, or waste-free circulation of meaning depends upon exclusion. For while a restricted economy entails no loss, it is founded upon an originary loss or expulsion, which once made can never be reclaimed, as in the Bible. Whether as organism or as enterprise, the restricted economy defines itself against the embarrassing surplus it cannot contain. It coheres in itself as a precariously balanced system from which all further exclusion is precluded. There can be no “non-productive expenditure” in a restricted economy, nothing that does not circulate: the “circle of power” is closed

This distinction between “restricted” and “general” economies of consumption is key to understanding Milton’s ontology of eating as portrayed in Paradise Lost and Regained. In Book VII of Paradise Lost, Milton portrays the creation itself as a divine expulsion, a cosmic purgation of waste:

”It is not a little curious that, with the exception of Ben Jonson (and he did not speak gravely about it so often), the poet in our own country who has written with the greatest gusto on the subject of eating is Milton. He omits none of the pleasures of the palate, great or small. In his Latin poems, when young, he speaks of the pears and chestnuts which he used to roast at the fire with his friend Diodati. Junkets and other “country-messes” are not forgotten in his “Allegro.” The simple Temptation in the Wilderness, “Command that these stones be made bread” (which was quite sufficient for a hunger that had fasted “forty days”), is turned, in Paradise Regained, with more poetry than propriety, into the set out of a great feast, containing every delicacy in and out of season. The very “names” of the viands, he says, were “exquisite.” And in Paradise Lost, Eve is not only described as being skilful in paradisaical cookery (“tempering dulcet creams”), but the angel Raphael is invited to dinner, and helped by his entertainers to a series of tid-bits and contrasted relishes– Taste after taste, upheld with kindliest change. ( Denise Gigante )

Such triumphs of heroic eating were not considered selfish. The rich man’s table is part of the machinery of wealth distribution. His demand attracts supply. His waste feeds the poor. Food- sharing is a fundamental form of gift exchange, cement of societies; the chains of food distribution are social shackles. They create relationships of dependence, suppress revolutions and keep client classes in their place.

The fruit whose “mortal taste” was the source of all our woe did, after all, grow on the tree of knowledge. Eating, sin, and guilt have always constituted a powerful holy trinity connected to the broader relationship of pleasure and morality. Throughout Milton’s Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained, Milton plays with the epistemological connotation of taste ;Samson Agonistes, whose blind hero declares, “The way to know were not to see but taste” . At the time Milton was writing, however, taste was philosophically connected not only to knowledge and pleasure, but to morality as well.

…”Not just one hot dog, but as many hot dogs as humanly possible over a 10-minute span in Nathan’s Famous 95th annual July 4 hot dog-eating contest on Coney Island. Mr. Kobayashi is a full-time, globe-trotting competitive eater and a six-time champion in an event featuring a US$10,000 first prize. (His personal best: 54 hot dogs.)

On Independence Day, the day of his arrest for trespassing, resisting arrest, disorderly conduct and obstruction of justice, Mr. Kobayashi was not onstage alongside the other eaters when the gorging began, but standing amid the crowd wearing a black T-shirt with “Free Kobe” on the front. It was a one-man protest aimed at Major League Eating, the Major League Baseball of the competitive dining game that binds professional eaters to allegedly onerous contracts, such as the document Mr. Kobayashi refused to sign in advance of the Coney Island classic.”…

At the origins of the British empirical discourse of taste, this link between epistemology, aesthetics, and ethics, inquires and has found the ideals of the true, the good and the beautiful inevitably bound up with the philosophic complexity of taste. And viewed from the broader perspective that includes Milton, taste becomes more than a question of mere subjective discernment; it becomes constitutive of human subjectivity. From the “mortal taste” of the opening lines of Paradise Lost to the final lines of Paradise Regained, in which the Son of God goes on his way “from heavenly feast refreshed” . Milton makes taste–figuratively displayed as physiological taste, or eating–a means of establishing subjective particularity. His fictional ontology of eating, in short, becomes a system for the production of tasteful subjects.

''Dante's Divine Comedy reveals the true essence of this sin, as those lost souls in the circle of the gluttons partake of a cold mouthfull of mud and muck. In Dante's hell, this sin is devoid of all the conviviality that attends it in this life, and all we are left with is what Dame Dorothy Sayers called a "cold sensuality, a sodden and filthy spiritual wretchedness." The images of the three-headed dog Cerberus, ravenously eating the miry much that Dante's guide, Virgil, throws at him, and the unfortunate character Ciacco, condemned to this state for eternity, drive home to us the animal-like nature of this vice. In hell, gluttony is no longer fun.''

Taken together, Paradise Lost and Regained comprise what William Kerrigan has called “the great myth of the evil meal” . Such a myth asks us to take seriously the ontological power of eating, and the proposition that, in Paradise Lost, paradise was lost because Eve and then Adam ate. Critics have observed that within the poem Milton reduces the Fall to four highly charged words: “she pluck’d, she eat” When the Son of God descends to pronounce judgment on the transgressors, he demands: “hast thou eaten of the Tree / Whereof I gave thee charge thou shouldst not eat?” . After floundering eloquently enough for a while, Adam admits: “Shee gave me of the Tree, and I did eat” . Also deflecting blame, Eve responds: “The Serpent me beguil’d and I did eat” . In Milton’s text, as in Genesis 3, both the question and the two responses it generates are thus punctuated with the word “eat.” Visually, it dangles from the end of each line like the forbidden fruit itself, suggesting something sinful about eating, as if paradise were lost because despite whatever else they were doing, Adam and Eve ate.

'' Grande Bouffe (aka Blow-Out), the film for which Ferreri is best-known outside of his native Italy, is one of the most extraordinary European films of the 1970s. Opening the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, it polarized critics and immediately aroused intense controversy - which no doubt helped it become one of the highest-grossing French films of the decade. The film details the pact made between four bourgeois men (pilot, chef, magistrate and TV producer), all bound by their love of food, who retreat to a villa on the outskirts of Paris in the company of three prostitutes, there to gorge themselves to death on food and sex.''

The objection will be raised that they did not simply eat, but that they ate unlawfully, in disobedience of the Word. The poem centers on the distinction between forbidden and permitted food, and what are the right weights, measures and recipes that govern paradise and permit entry to it.

Derrida’s interrogation of the moral implications of eating may shed new and possibly unexpected light on the familiar narrative “To pluck and eat” ; “ye shall not eat” ; “she pluck’d, she eat” ; and so forth. While his reference to eating as a “metonymy of introjection” refers to the psychological process of incorporating, idealizing, and psychically cannibalizing a lost object of desire, his understanding of it derives from Kant’s third Critique: his critique of aesthetic judgment, or taste.

In Derrida’s account of Kantian taste, the aesthetically consuming subject processes the world according to a certain economic logic, a cycle of return that takes in through the mouth and gives back in the form of expression. As the place of tasting and consumption, as well as expression, the mouth is “no longer . . . situated in a typology of the body” but instead becomes the os of the system, organizing all sites unto itself . What is articulated between the lines of Derrida’s account, therefore, is that taste takes place in the mouth. Eating entails a digestive insistence that taste in its pure aesthetic mode does not, and hence a certain digestive surplus. In order to avoid indulging in a cycle of coprophagy, therefore, the figuratively eating ,or tasting, subject must inhabit a world that comes pre-purged of all such unseemly excess, or everything that will not cleanly pass through the mouth.

''In more recent years, competitive eating has left the fairgrounds of America and gone global. Mr. Kobayashi, whose nickname, naturally enough, is The Tsunami, has won contests all over Japan and throughout Southeast Asia. ''

” ‘He has signed contracts in the past with MLE, but this year, for some reason, there was a much higher level of exclusivity. There were clauses in the contract that said, for example, ‘You can’t publicly participate in any event where you eat quickly or you eat a lot,’ ” says Mr. Kobayashi’s New York attorney, Mario Romano. “It prevents him from going anywhere else in the world and being in any other type of contest where you have to eat fast, which was ridiculous., ”

Spectators at the Nathan’s eat-off appeared to agree and roared lustily when the former champion mounted the stage amid chants of, “Let him eat! Let him eat!” Collared by police, the renegade hot-dog lover was carted away in handcuffs, his message of protest sent though his hunger far from sated….

The fundamental law of Christian consumption holds that subjects are made by eating the Word of God,in a lapsarian world, the Word made flesh, and for Milton, as for other Protestants, the symbolic nature of that meal is crucial. If flesh is literally eaten, one is transported out of the sacramental and into the superstitious, the irrational sphere of sheer idolatry. Milton’s anti-Catholic In quintum novembris, perhaps his most graphic portrayal of episcopal idolatry, describes a pageant in which “the wearer of the Triple Crown, borne on men’s shoulders makes a circuit of the whole city, carrying with him hisgods made of bread” . Within the context of the poem, these bready gods appear as a type of absurdity. Yet allegorically what they do suggest is the economic nature of the cycle of consumption that defines and propels Christianity. In Milton’s day, bread was inscribed in an economic register. In In quintum novembris, Milton’s “gods made of bread” circulate through the city like pocket change to be dispersed by the wearer of the Triple Crown: a progress that serves as a parodic allegory of the consumptive economy of Christianity.

''In more recent years, competitive eating has left the fairgrounds of America and gone global. Mr. Kobayashi, whose nickname, naturally enough, is The Tsunami, has won contests all over Japan and throughout Southeast Asia. ''

Milton’s denial of the literal nature of the mandate to accept sacrifice and eat flesh was part of the phenomenon whereby “Reformed theology not only abolished the pageantry of the Roman rite but rejected the sacrificial character of the Eucharist altogether,” as Deborah Shuger explains: “The moral inwardness of Protestantism–its ethical rationalism, which drives its antipathy to the spectacular ‘magic’ of the Mass–also problematizes sacrifice”.

But what does it mean to “problematize sacrifice”? To call into question what is, etymologically, sacred making? Georges Bataille, upon whom Derrida relies for his economic understanding of taste, argues that sacrifice entails a fundamental loss at the center of Christianity: “From the very first, it appears that sacred things are constituted by an operation of loss: in particular, the success of Christianity must be explained by the value of the theme of the Son of God’s ignominious crucifixion, which carries human dread to a representation of loss and limitless degradation” . Thus, Milton observes that in the Mass “Christ is sacrificed each day by the priest . . . [his body] is supposed to be made out of bread at the moment when the priest murmurs the four words, this is my body, and to be broken as soon as it is made” [Prose 6: 559]

Yet if this sacrifice or “loss” at the core of Christianity is exposed as mere absence–if God is to be allegorically aligned with bread and to operate as mere sign, if he is to circulate economically rather than to remain in his original unity as the Un-exchangeable, the divine Presence sustaining the Christian economy of consumption–does this not destabilize the traditional view that God “gives more than he promises, [that] he submits to no exchange contract, his overabundance generously breaks the circular economy”?

Does the Protestant rejection of the sacrificial character of the Eucharist, in other words, not set in motion a chain of subjective deferral whereby the would-be subject is always at least one step removed, not only from God, the master-signifier of the consumptive economy, but from his or her own presence as well? If the Christian subject is dependent for subsistence (indeed existence) on flesh, what happens when one instead ingests a vacuity that installs itself at the constitutive center of self, like a gap perpetually craving the real presence of flesh?

'' it took me a full 10 days to get through the entirety of Marco Ferreri's La Grande Bouffe, and frankly, I'm still not entirely sure how I feel about it. When the film was first shown at Cannes in 1973, Catherine Deneuve, who was married to one of the film's stars, Marcello Mastroianni, stopped speaking to him for a week. Ingrid Bergman reportedly had to leave the theater in a fit of nausea, and commented afterwards that she was almost speechless with disgust. ''

Milton’s denial of the literal nature of the mandate to accept sacrifice and eat flesh was part of the phenomenon whereby “Reformed theology not only abolished the pageantry of the Roman rite but rejected the sacrificial character of the Eucharist altogether,” as Deborah Shuger explains: “The moral inwardness of Protestantism–its ethical rationalism, which drives its antipathy to the spectacular ‘magic’ of the Mass–also problematizes sacrifice”. But what does it mean to “problematize sacrifice”? To call into question what is, etymologically, sacred making?

”…For the gorgers, the motivation in a sport where nobody, not even mega-stars such as Mr. Kobayashi is getting rich, is fame. Fame often takes the form of a video clip on You-Tube that goes viral. For restaurants or products, for instance, Nathan’s Frankfurters, a contest is just another form of advertising.

“Part of the attraction for the competitive eaters is popularity, and there is no doubt that the Internet has played a huge role in that,” says Arnie Chapman, the chairman of All Pro Eating Promotions and the reigning world record holder for hard sour pickles consumed in a single sitting. (Think: 2.94 pounds in three minutes and 45 seconds).” ( Joe O’Connor, National Post )

This nightmare fantasy of “Christ’s actual flesh” passing through the Christian subject in so literal a fashion arrives at its logical (though horrible) conclusion: that “after being digested in the stomach, it will be at length exuded.” The unspiritual, uncivilized possibility that God can be physically digested and then exuded results in the Protestant defense of excluding him from the Host–extruding him, so to speak, from the extrusion. However, such an exclusion conflicts with Milton’s own monist cosmology, whereby God is in all matter.

”Even in the modern west, until the 20th century, habits of atavistic overeating recurred in high-status individuals, even though society had abundant other ways of honouring rank. Pride in big meals and bodily corpulence survived the medieval demonisation of gluttony in the Middle Ages and the neo-stoical cult of moderation which was part of the “civilising process” of the Renaissance and early modern times. Waists were barely slimmed by the 19th-century cult of the Romantic waif. It is perhaps not surprising that revulsion towards fat took so long to become normal in our culture. It is a striking reversal of a long-standing evolutionary trend. From a biologist’s point of view, the human body can be seen as a startlingly efficient repository for fat, which we secrete in relatively large amounts and deposit more widely around our bodies than any other land mammal. A healthy, normal-sized western woman today has a body that is, on average, 30 per cent adipose tissue: not even polar bears and penguins can rival that level of attainment. Esteem for fatness was part of the earliest aesthetic we know of: the prejudice in favour of big-hipped, bosomy beauties in Stone Age carvings.

''"Gluttony is an inordinate desire to consume more than that which one requires." Character is aesthetic, pretty and (in her way) attractive. Some symbolic explanations: Abundance of textiles - this sin not only as eating and drinking, but consuming in it's wider meaning, such as buying and gathering useless things etc Grapes - "luxury" goods, connected with lavish parties (in ancient times) etc The pink colour theme - grapes, sweets etc''

”Now, however, the era of esteemed adiposity is over in the west. Obesity is a disqualification for status. The last really fat US president was William Howard Taft, who was so enormous that he could not tie his own shoelaces. Nowadays, that level of obesity would weigh down any political career. Bill Clinton, who was not particularly fat, suffered almost as much obloquy for his slack waistline as for his loose morals. Dieting is now as much de rigueur for politicians as for female entertainers. Big corporations sack the fat and discriminate in favour of the thin in appointments and promotions. The fat are in danger of self-reclassification as a persecuted minority: that, indeed, is the message of the quaintly named “National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance”. Obesity has to justify itself as a form of disability, demanding “equal rights” for fat people: fat-friendly turnstiles, extra-long car seat belts.” (Philip Fernandez-Armesto )

COMMENTS

COMMENTS