His economic ideas belong in the bone yard, and his understanding of organizational decision making resembles that of ”a camel is a horse designed by a committee ” school. But his ideas on aesthetics and art, likely a byproduct of his critique, match the sweep with some depth. Indeed, Marcuse in the end thinks that it is through art, or the aesthetic dimension, that ultimately social tranformation is to be achieved. Once we shed the idea of affirmative culture and museal art as an autonomous domain of private, personal, and inner experience, the liberatory values of art are released into the world and reveal to us the oppressive and unacceptable nature of material life conditions.

His theory claimed that Bourgeois society depends on affirmative culture both, to justify its rule (so as to differentiate itself from l’ancient regime) and its idealism forms a way of distracting away from oppression by pointing to inner liberation through spiritual ideals.The problem is with the idea of art as ”affirmative” . It is the negative or critical potential of art that provides the means of material transformation and true liberation, but the affirmative component drives the wheel of commerce.

”This is this problematic of the totalising effects of technology and of art itself that provides I think the backdrop and a point of departure for Marcuse’s concern with art and revolution. Marcuse sees art as at once concervative and as having revolutionary potential. In his view art is conservative if it is positive or affirmative, that is, if it posits particular values or practices a central or definitive of a culture, as for example, in the case of ‘national art’ or ‘high art’. On the other hand, art does embody the liberatory values, that is, it does focus nontechnological practices, on in Marcuse’s preferred terms, high art embodies the liberatory values of bourgeois art. Affirmative culture, according to Marcuse, is art that is placed at the centre, that embodies the values of the dominant classes.”

''I have no wish to soften the saying that to write lyric poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric; it expresses in negative form the impulse which inspires committed literature. The question asked by a character in Sartre’s play Morts Sans Sepulture, “Is there any meaning in life when men exist who beat people until the bones break in their body?’ is also the question whether art now has a right to exist; whether intellectual regression is not inherent in the concept of committed literature because of the regression of society''. Adorno, “Commitment”

Herbert Marcuse, a seemingly modern man, was an oddly ambiguous figure on the contemporary intellectual scene. His message, for all its tricking out in the dress of neo-Marxism and Freudianism was to say the least, somewhat unique and slightly antique, yet with the present growing ideological divisions in Western society, Marcuse remains a divisive figure whose specter continues to cast his shadow. Even if the message was an old one, the question must still be asked: is it relevant and credible today?

Our present age has borne witness to the most rapid expansion of military and state power in human history. Weapons have grown highly sophisticated in a complex lockstep with global economic and political transformations. The meaning of this enormous growth in power, and the implications for our increasing technological sophistication, is anything but clear and unambiguous. The political mythology surrounding war and peace has also grown in sophistication. Nonetheless, the tool inevitably varies with the specific relationship. That is, the conditions under which it becomes possible, and the situations which it makes possible. This internal capacity for variation and variance is closer to the essence of war than the complex matrix of state and global power relations.

Any tool can become a war machine ; at least potentially, and if its object becomes war. Yet war is still not the essence of the war machine, but rather the set of conditions under which the machine becomes appropriated by state power, or even the global order in which states now become only parts. In Deleuze and Guatarri’s account, a war machine is always external to the powers of the state, even though the state may have means for capturing and transforming its power into violence for its own ends.

''The lofty prize Of science lies Concealed today as ever! He has no thought To him it’s brought To own without endeavor!'' Goethe, Faust

There is much in Marcuse’s doctrine that is true, or at least appears so, if only ostensibly. The middle-class society that he saw emerging in western Europe and America, Marcuse’s advanced industrial society, does operate in totalitarian modes, does tend to stifle, smother and marginalize alternative visions which amounts to a large extent, a crashing bore that oscillates between the middle and the almost smart segment of society. In other words, the status quo and stagnancy, which, though pacifying and reassuring, does tend to victimize the extremes, for bett

nd worse, but tends overall to underline the ”murkiness” of what is reality.”Does matter dramatize ideas into reality, or do ideas awaken things into being? A code documents a becoming, hence it is not a relationship as such, though it may be connected or disjoined from other codes. What is coded does not necessarily resemble the code which is applied: in fact these cases constitute rather singular exceptions, which have formed the morphological substructure of the concept itself.”

''In the disparity between the awareness of unreason and the awareness of madness, we have, at the end of the eighteenth century, the point of departure for a decisive movement: that by which the experience of unreason will continue, with Holderlin, Nerval, and Nietzsche, to proceed ever deeper towards the roots of time — unreason thus becoming, par excellence, the world’s contratempo — and the knowledge of madness seeking on the contrary to situate it ever more precisely within the development of nature and history. It is after this period that the time of unreason and the time of madness receive two opposing vectors: one being unconditioned returned and absolute submersion; the other, on the contrary, developing according to the chronicle of a history''. Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization

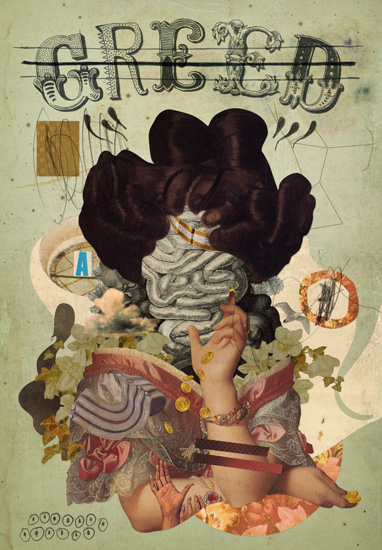

But, the question is, how high in fact are the aspirations of mankind? What is the capacity for comprehension, and what is the willingness to ”take their game”to the next level? Marcuse would have us believe that the plebs could live in a kind of ecstasy; but how well did Marcuse know his plebians? Likely, not much. He was an ivory tower type and the bottom quintile may have been seen as an abstract idea, and a context that could be idealized.

And Marcuse may be right when he points out the ultimate irrationality of an economy, which provides the affluence that buys off dissent, that is based on the final madness: production of a war machine that constantly needs new enemies balanced against the risk of plunging the world towards complete or limited annihilation. There are always new gophers needed to club back into their holes. But if ”advanced industrial society” is a useful generic term, what of the affluence of Japan and Germany after WWII, who built their economic prosperity on a civilian sector, without a major war industry, or the rise of today’s service economies that defy completely the standard Marxian conceptions of productive resource?

''If there is something in literature which does not allow itself to be reduced to the voice, to epos or to poetry, one cannot recapture it except by rigorously isolating the bond that links the play of form to the substance of graphic expression.'' Jacques Derrida

Marcuse’s prose is tangled, the references are abstruse, and much had appeared before in more popular form at the time such as Vance Packard’s ”The Hidden Persuaders” and Fred J. Cook’s ”The Warfare State” . But Marcuse’s genius was to inverse populism; he made abtsruse thinking accessible to the masses. Marcuse took popular doctrine and cloaked it in ideology and quite dense prose. Hence his appeal to the self-conscious dissidents among the campus crowd. Rebels who would not be caught dead with the Book of the Month. But Marcuse had made it all right, and hip to flip the peace sign. You could not cite Vance Packard as witness for the revolution; but you could cite Herbert Marcuse.

''Intelligence is a moral category. The separation of feeling and understanding, that makes it possible to absolve and beatify the blockhead, hypostasizes the dismemberment of man into functions. Praise of the simpleton has an undertone of anxiety lest the severed parts reunite and put an end to the derangement. ‘If you have understanding and a heart,’ a verse of Holderlin’s runs, ‘show only one. Both they will damn, if you show both together.’'' Theodor Adorno

In the final analysis Marcuse is somewhat of a two dimensional thinker. There is a lot of fascinating sweep, but the depth is less obvious. For angry black militants to have talked revolution is forgivable, probably justified and certainly understandable. For the Students for a Democratic Society, their mouthing of the slogans of violence and revolution also had a certain coherence. Americans, by and large, do not appreciate how precarious a thing civilization is, and what potential volcanic evil lies under the seemingly placid surface of humanity, particularly men. White Americans, old and young, have been insulated from the experience of evil certainly since the days of the Civil War. But not Marcuse.

He was born in Berlin in 1898, and was forced to flee Hitler in 1934. It remains to be known whether Marcuse was one of those who subscribed to the doctrine of ”Social Fascism” , the extra-ordinary lunact on the far left of the Weimar Republic that held the ”lying” Social Democrats, rather than the Nazis to be the chief enemy. But Marcuse shared in the early unanimous leftist intellectual’s complaint that, in the words of Paul Cassirer, the so-called democratic revolution in post World War I Germany was ”nothing but a great swindle: schiebung” For these men, the lying and compromise of the Weimar Republic were unendurable, until the Nazis taught them, that things could be much worse. But in social and psychological theory, Marcuse is not that easily dismissed.

In Eros and Civilization, Herbert Marcuse presents Freud at the level of metaphysical psychology. That is: we find Freud engaged in overturning “conventional” metaphysics through psychoanalysis — methodically substituting pleasure and imagination for reason and logic — but paradoxically in so doing he produces a “theoretical” practice which, through its “diagnostic” methodologies and even in its “axiomatic” structure, still reflect profoundly traditional conceptions of humanity. For example, Freud analyzes the principle or essence of being (of organic life) as Eros — in contrast to the traditional understanding of being as Logos. This ontological dimension revealed in psychoanalysis is what allows Freud to interpret Eros as corresponding in a ubiquitous way to the death drive. The erotic instinct and the death drive are fused together in Freud’s interpretation in precisely the same way as the metaphysical principles of being and of non-being.

'' In any case, Bergson is not one of those philosophers who ascribes a properly human wisdom and equilibrium to philosophy. To open us up to the inhuman and the superhuman (durations which are inferior or superior to our own), to go beyond the human condition: This is the meaning of philosophy, in so far as our condition condemns us to live among badly analyzed composites, and to be badly analyzed composites ourselves'' (Gilles Deleuze, Bergsonism pg 27-28).

Freud interprets being in terms of Eros, repeating a formative moment in Plato’s philosophy — a conception of culture not as a repressive sublimation, but as the “free self-development of Eros.” Marcuse notes that even in Plato this concept presents itself as an archaic-mythical remnant or “residue.” So being strives for pleasure, which becomes an aim for organic life — human culture in particular: “The erotic impulse to combine living substance into ever larger and more durable units is the instinctual source of civilization.” In short, the sex instincts are life instincts, principles of organic being: “the impulse to preserve and enrich life by mastering nature in accordance with the developing vital needs is originally an erotic impulse.” The struggle for existence is not the unending struggle against death, but originally a struggle for pleasure: “culture begins with the collective implementation of this aim.” The erotic desire is organizational, super-ordinary; but it is only much later that the striving for existence itself becomes organized in order to dominate life.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS