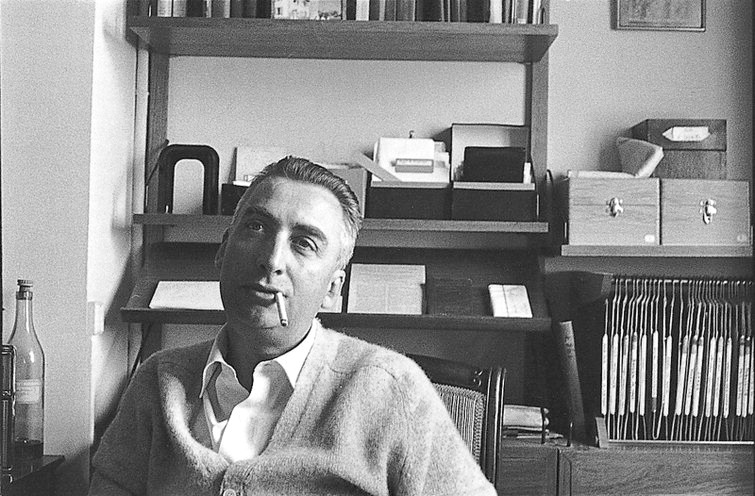

With righteous indignation, structuralism, and something called semiotics, a multi-faceted Frenchmen named Roland Barthes captured a large audience with his social and literary criticism. Roland Barthes is a key figure in international intellectual life. He is one of the most important intellectual figures to have emerged in postwar France and his writings continue to have an influence on critical debates today. “Mythologies” is one of his earliest and most widely-read works. Mythologies is one of Barthes’s most popular works because in it we see the intellectual as humourist, satirist, master stylist and debunker of the myths that surround us all in our daily lives.

" In Roland Barthes Mythologies, we are - after several dozen articles on contemporary themes from politics and mass culture, from wrestling to soap adverts - given an essay that draws out some of the implications of the articles. In it, he explains that objects are not merely utilitarian or functional: there is no such thing as a car that is merely an operational device, that is resistant to cultural meanings, or a bar of soap that merely accrues pubic hair. These items, however functional, are saturated with connotations: and of course, these are produced by advertisers. This isn't simply a clever analysis of cultural artefacts, and nor is it depoliticised: for Barthes, these techniques are used to legitimise and naturalise power, they obscure what is historically produced by packaging it (the item, the situation) in a modern mythical structure. In his way, Barthes was really updating and expanding on the marxist theory of commodity fetishism and reification, showing how social relations were naturalised, how the traces of production were removed from commodities so that they appear as pristine, finished objects."

Best by many “écritures” available, how can a writer be honest? How can they dodge the implicit commitments? How can they avoid being alienated? Attempts to answer these questions constitute a major part of the history of modern prose. Some writers, one of the first being Flaubert, have tried what Barthes calls the “artisan” approach and have seated over their “mots justes” . Others have tortured and nearly murdered the language in their effort to get closer to reality. Some have retreated into a supposedly meaningful silence. And still others have sought to escape from dishonest “literature” by writing in an argot, a dialect, or some other sort of primarily oral language. Especially interesting to Barthes are those who, like Albert Camus in “L’Etranger” , have tried to invent a neutral, colorless, purely instrumental, absolutely cold prose; have tried that is, to get down to Barthes’ “le degré zéro de l’écriture”.

"In postwar France the car became the very symbol of modernity. This is reflected in a number of films of the period such as Lola (1960), La Belle Américaine (1961) and, more catastrophically, Jean-Luc Godard's Weekend (1967). The automobile industry was central to France's increasing industrialization with Renault's vast modern factory at Billancourt as its most visible reminder. This factory, incidentally, provided the setting for Claire Etcherelli's Élise ou la vraie vie (1967). In `La nouvelle Citroën' (Barthes: 1970 p.150-2) Barthes understands this perfectly and analyses the ways in which the car has become the very icon of France's modernization. He compares the car to a mediaeval cathedral: both are works produced by anonymous artists which enchant the masses."

The trouble, of course, is that each act of defiance has tended to become in its turn, a convention and, finally, one more ideological subterfuge, for the modern bourgeoisie is notoriously capable of transforming censure into praise and co-opting opponents. Barthes concludes, a bit dispiritedly, that modern prose can be only an anticipation and that there can be no complete solution to the problem of “decorative and compromising” “ecritures” without a social revolution. Double talk is the natural language of an ethically flawed society.

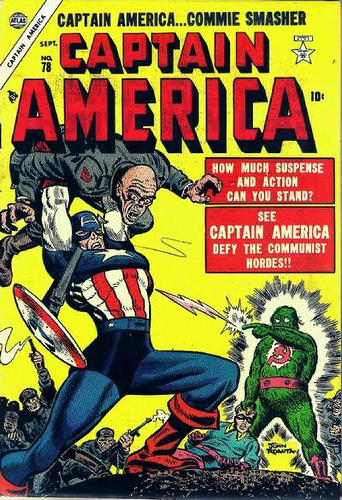

After the density of “Le Degré zéro de l’écriture” , the short witty essays collected in “Mythologies” may seem to be only light entertainment. They were written between 1954 and 1956 in response to occasional inspirations, and are concerned with such matters as Garbo’s face, wrestling matches, detergents, plastics, Martians and UFO’s, wine and milk, steaks and french fries, Chaplin, Billy Graham, strippers, astrology, and the politics of shopkeepers.

"Like Barthes – and unlike Ty Burr, above, who has the typical, pseudo-intellectual’s snobbish contempt of the sport – Aronofsky understands that wrestling is the oldest form of entertainment in any civilization for a reason: it is the archetypal representation of the human condition. It addresses the existential confusion, sorrow, and anger that people everywhere and in all times feel and have felt."

There are bright thoughts in the aphoristic “écriture” of the French seventeenth century. A discussion of a magazine sob sister’s advice to the lovelorn opens with the fine sententiousness: ” The heart is a female organ.” In an account of a guidebook we are given a law of the genre:”Christianity is the leading provisioner of tourism; one travels only to visit churches.” An essay on a child prodigy yields: “In the time of pascal childhood was considered a lost period; the problem was to get out of it as soon as possible. Since the Romantic era, since the triumph, that is, of the bourgeoisie, the problem is to stay in it as long as possible.”

"The space in between—what I like to call “the third way”—is where Slavin’s images perform the incommensurable, opening up a plenum. This is a fat world of deadpan peculiarity, achieving what Roland Barthes called the punctum—the pinprick, the essence, the wound or seminal moment elicited by an image. In Slavin’s photographs, this spreads through the fiber of each group of people, across the surface of an image that ultimately binds them together, like a coating of the bizarre and ridiculous related most closely to the freakdom of Diane Arbus. Slavin’s images share Arbus’ seeming impassivity, a sleight of hand that says, “I am not making you look like a freak; it’s just my camera capturing your soul.”

There is entertainment, too, in his habit of explaining presumably ignoble art in terms of the noble. Having observed that a professional wrestler exaggerates his plight when pinned down, Barthes adds: “The gesture of the vanquished wrestler signaling to the world a defeat which, far from concealing, he accentuates and “holds” in the fashion of a fermata in music, corrsponds to the ancient mask that was designed to signify the tragic tone…”

These essays are not, however, just deadpan divertissements and cultural slumming; they are also protests, like “Le Degré zéro de l’écriture” , against the humbug in our society. The piece on the advice to the lovelorn column becomes a denunciation of the way women’s magazines “amid trumpet blasts about Feminine Independence,” convert their readers into a “colony of parasites” dependent on men and wretchedly isolated from the real world. T

iece on the guidebook criticizes the kind of tourism that reduces a country to a museum.

"French critic and philosopher Roland Barthes circa 1960. His controversial and provocative book on Photography, Camera Lucida, was published in 1980 shortly before he was killed in a car accident. Roland Barthes wrote about still photography in a philosophical and experiential way. It strikes me that he, and many others before him who wrote about Photography in the twentieth century, were caught up in the fresh fascination of a new medium. Photography, for them, was a new art form exploring issues and ideas contemporary with their lives."

A review of the photographic exhibition “The Family of Man” condemns the sentimentality that stresses our common human lot; birth, work, death, and thus diverts attention from the unjust differences. Sometimes Barthes is ironical to the point of approval; he obviously likes the play acting of wrestlers, probably because in this instance the myth fools nobody. But he is relentless against the alibis of the well-off, the paltering of admen, the dream-mongering of the popular press, and every sort of modern tartuffe.

“The virtue of all-in wrestling is that it is the spectacle of excess. Here we find a grandiloquence which must have been that of ancient theatres. And in fact wrestling is an open-air spectacle, for what makes the circus or the arena what they are is not the sky (a romantic value suited rather to fashionable occasions), it is the drenching and vertical quality of the flood of light. Even hidden in the most squalid Parisian halls, wrestling partakes of the nature of the great solar spectacles, Greek drama and bullfights: in both, a light without shadow generates an emotion without reserve. ( Barthes)

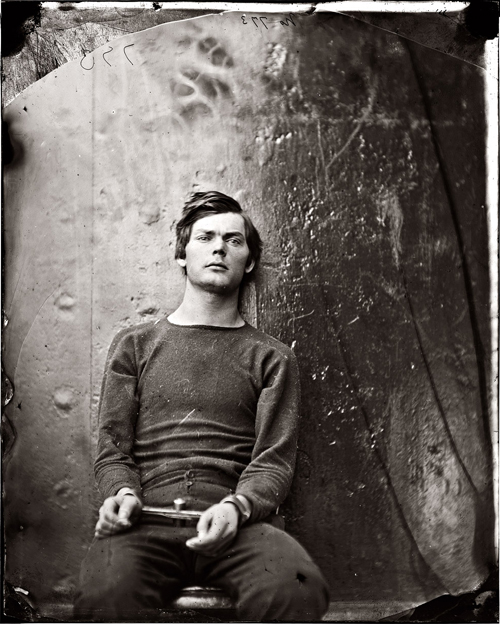

This photo taken of would be assassin Lewis Payne by Alexander Gardner in 1865 haunted Roland Barthes. Barthes then drives home his philosophical nail quite close to my heart as he describes his reaction to a photograph of a jailed young assassin. “I now know that there exists another punctum (another “stigmatum”) than the “detail.” This new punctum, which is no longer of form but of intensity, is Time, the lacerating emphasis of the noeme (“that-has-been”), its pure representation. In 1865, young Lewis Payne tried to assassinate Secretary of State W. H. Seward. Alexander Gardner photographed him in his cell, where he was waiting to be hanged. The photograph is handsome, as is the boy: that is the studium. But the punctum is: he is going to die.”

There are people who think that wrestling is an ignoble sport. Wrestling is not a sport, it is a spectacle, and it is no more ignoble to attend a wrestled performance of Suffering than a performance of the sorrows of Arnolphe or Andromaque [Barthes here refers to characters in neo-classic French plays by Molière and Racine]. Of course, there exists a false wrestling, in which the participants unnecessarily go to great lengths to make a show of a fair fight; this is of no interest. True wrestling, wrong called amateur wrestling, is performed in second-rate halls, where the public spontaneously attunes itself to the spectacular nature of the contest, like the audience at a suburban cinema. Then these same people wax indignant because wrestling is a stage-managed sport (which ought, by the way, to mitigate its ignominy). The public is completely uninterested in knowing whether the contest is rigged or not, and rightly so; it abandons itself to the primary virtue of the spectacle, which is to abolish all motives and all consequences: what matters is not what it thinks but what it sees.

" One key example of this is wrestling discussed in the article `Le monde où l'on catche' (Barthes: 1970 pp.13-24). Wrestling is often thought of as the least intellectual pastime in our culture and is dismissed as vulgar fodder to the uneducated masses. What Barthes does, in a striking and provocative gesture, is claim that wrestling and its audience are in fact every bit as sophisticated as high drama or opera"

This public knows very well the distinction between wrestling and boxing; it knows that boxing is a Jansenist sport, based on a demonstration of excellence. One can bet on the outcome of a boxing-match: with wrestling, it wold make no sense. A boxing-match is a story which is constructed before the eyes of the spectator; in wrestling, on the contrary, it is each moment which is intelligible, not the passage of time. The spectator is not interested in the rise and fall of fortunes; he expects the transient image of certain passions. Wrestling therefore demands an immediate reading of the juxtaposed meanings, so that there is no need to connect them. The logical conclusion of the contest does not interest the wrestling-fan, while on the contrary a boxing-match always implies a science of the future.

"I'm sure there are other reasons these dates are significant, but I find them interesting because on both days Bob Dylan hung out a bit with Charlton Heston. Now, not to dive into the deep end of French literary theory but one favorite distinction gleaned from that work was Roland Barthes' notion of the writerly and readerly texts. Put simply, the meaning in readerly texts is fixed and rigid, but in writerly texts the meaning is more fluid, more open. Barthes said "In readerly texts the signifiers march; in writerly texts, they dance." As artists, the difference between Bob and Chuck seems pretty clear. In 1997, Dylan and Heston were in the group of five artists honored by President Clinton at The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. In 1968, both men were also together in Washington with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and a quarter of a million men and women marching together for social justice. "

In other words, wrestling is a sum of spectacles, of which no single one is a function: each moment imposes the total knowledge of a passion which rises erect and alone, without ever extending to the crowning moment of a result. Thus the function of the wrestler is not to win: it is to go exactly through the motions which are expected of him. It is said that judo contains a hidden symbolic aspect; even in the midst of efficiency, its gestures are measured, precise but restricted, drawn accurately but by a stroke without volume. Wrestling, on the contrary, offers excessive gestures, exploited to the limit of their meaning. In judo, a man who is down is hardly down at all, he rolls over, he draws back, he eludes defeat, or, if the latter is obvious, he immediately disappears; in wrestling, a man who is down is exaggeratedly so, and completely fills the eyes of the spectators with the intolerable spectacle of his powerlessness.

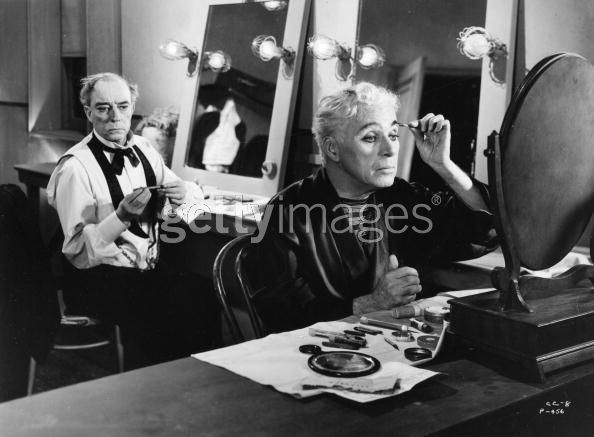

"The same year, he praised Charlie Chaplin as a Brechtian artist, showing “the public its blindness by presenting at the same time a man who is blind and what is in front of him,” that is, “a kind of primitive proletarian, still outside Revolution” in MODERN TIMES. Twenty-five years later, in a regular column he was writing for Le Nouvel Observateur, he expressed his fascination with an image from LIMELIGHT—Chaplin applying makeup in front of a mirror-as “literally a metamorphosis, such as only mythology and entomology could speak about it.” And a few years before that, writing about himself in the third person in Roland Barthes, R B. had this to say: As a child, he was not so fond of Chaplin’s films; It was later that, without losing sight of the muddled and solacing ideology of the character, he found a kind of delight in this art at once so popular (in both senses) and so intricate, it was a composite art looping together several tastes, several languages Such artists provoke a complete kind of joy, for they afford the image of a culture that is at once differential and collective plural This image then functions as the third term, the subversive term of the opposition in which we are imprisoned mass culture or high culture."

This function of grandiloquence is indeed the same as that of the ancient theatre, whose principle, language and props (masks and buskins) concurred in the exaggeratedly visible explanation of a Necessity. The gesture of the vanquished wrestler signifying to the world a defeat which, far from disgusting, he emphasizes and holds like a pause in music, corresponds to the mask of antiquity meant to signify the tragic mode of the spectacle. In wrestling, as on the stage in antiquity, one is not ashamed of one’s suffering, one knows how to cry, one has a liking for tears.” ( Roland Barthes )

"Roland Barthes, conversely, sees her face as the emblem of the asexual ideal to which the classical cinema aspired: Garbo still belongs to that moment in cinema when capturing the human face still plunged audiences into the deepest ecstasy, when one literally lost oneself in a human image as one would in a philtre, when the face represented a kind of absolute state of the flesh, which could neither be reached nor renounced. . . . it is not a painted face, but one set in plaster, protected by the surface of the colour, not by its lineaments. . . . not drawn but sculpted in something smooth and friable, that is, at once perfect and ephemeral. . . . Garbo offers to one's gaze a sort of Platonic Idea of the human creature, which explains why her face is almost sexually undefined, without however leaving one in doubt "

… Barthe’s Marxism and his existentialism appear in “Mythologies” in the form of attacks on the “bourgeois norm” and on the complacent tacit assumption, which he ties to philosophical essentialism, that our spuriousness and silliness are somehow built-in instead of being produced by historical circumstances that can be controlled- if need be, by a violent political revolt. “I was trying”, he explains in his foreword, ” to reflect regularly on certain myths in french daily life… the point of departure for this reflection was most often a feeling of impatience when confronted by the ‘naturalness’ with which the press, art, and the common sense constantly dress up a reality which, even though it is one we live in, is nevertheless completely historical; in brief, it pained me to see nature and History confused at every turn in accounts of our daily behavior, and I wanted, in this decked out display of what goes without saying, to get hold of the ideological abuse which in my opinion is hidden there.”

Toward the end of the book he returns to this theme, insisting that what is called human nature in a capitalist society is mostly just a set of customs that are convenient and profitable for the dominant class. In all this there is an evident implication that a myth , in the special sense under scrutiny, is a piece of ideological double-talk comparable to an “écriture” with allowances for the frequent use of images or actions or other substitutes for words.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS