“Artaud saw in Vincent van Gogh a faithful replica of his own torment. After the painter’s suicide he wrote: Dr. Gachet would not tell van Gogh that he was there to straighten out his painting (…) but he used to send him to paint from nature, and bury himself in a landscape to escape the pain of thinking. Except that, as soon as van Gogh had turned his back, Dr. Gachet turned off the switch of his mind. (…) I myself spent nine years in an insane asylum and I never had the obsession of suicide, but I know that each conversation with a psychiatrist, every morning at the time of his visit, made me want to hang myself, realising that I would not be able to cut his throat.

In Artaud’s view, Van Gogh had been “suicided by society” (the “executioners”): Besides, one does not commit suicide by oneself. No one has ever been born by oneself. No one dies by oneself either.”

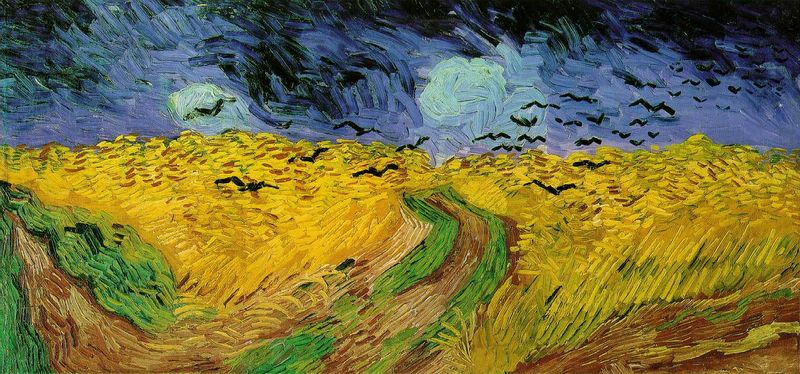

Crows Over a Wheatfield. menacing and ominous in its great swath of land and sky, was one of the last canvases that Vincent Van Gogh painted. Crows beset him whenever he painted in the countryside around Auvers, and it may have been to frighten them away that he borrowed the pistol he was later to turn on himself.

In 1947 Antonin Artaud, the French art critic and playwright, whose entire life had been a struggle between the sometimes conflicting and sometimes allied forces of madness and artistic expression, published a slim volume about a kindred spirit. It was entitled “Van Gogh, le Suicide de la Societe”. The tone of the book, that of barely controlled fury, seemed to derive from Artaud’s identification with the dead painter. Both men had suffered from sporadic attacks of mental illness and had been committed to institutions for the insane. Van Gogh voluntarily for about a year, Artaud against his will for nine years. Using Van Gogh’s case as an example, Artaud announced that doctors were the natural enemies of artists. Artists were subversives who challenged a society’s established values, while the doctors who treated them were the guardians of those values, their unavowed mission to destroy the artist.

"Antonin Artaud was prompt at rejecting floating abstractions, beliefs, common-sense and the glorified gobbledygook that passes for mental sanity among ordinary citizens. He was a threat to "normal" people, although less as an eccentric or a drug addict (like many visionary artists) than in his way of unsettling the communicative functions of language."

Artaud’s rambling indictment named as the villain in Van Gogh’s death the last doctor to treat him. Paul-Ferdinant Gachet, who lived in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, about twenty miles from Paris.” If Van Gogh had not died at 37, ” Artaud wrote, ” I don’t need the Grim reaper to tell me with what supreme masterpieces painting would have been enriched…Two days before his death, an evil spirit and improvised psychiatrist called Doctor gachet was the direct, efficient, and sufficient cause of his death…. the firm and sincere conviction that Dr. Gachet , psychiatrist, in reality hated Van Gogh as a painter, and above all as a genius.”

“This is why a tainted society has invented psychiatry to defend

itself against the investigations of certain superior intellects

whose faculties of divination would be troublesome.

No, van Gogh was not mad, but his paintings were bursts of Greek

fire, atomic bombs, whose angle of vision would have been capable

of seriously upsetting the spectral conformity of the

bourgeoisie.

In comparison with the lucidity of van Gogh, psychiatry is no

better than a den of apes who are themselves obsessed and

persecuted and who possess nothing to mitigate the most appalling

states of anguish and human suffocation but a ridiculous

terminology. To a man, this whole gang of respected scoundrels

and patented quacks are all erotomaniacs.

[Artaud defines a “madman” as] a man who preferred to become mad,

in the socially accepted sense of the word, rather than forfeit a

certain superior idea of human honor.

So society has strangled in its asylums all those it wanted to

get rid of or protect itself from, be

its accomplices in certain great nastiness….”

Artaud, more than fifty years removed from the event, had never met Dr. Gachet and did not have a shred of evidence to support his accusation. Dr. Gachet, Dr. gachet was known to have befriended and helped Van Gogh in the last period of his life and, when Vincent shot himself, it was Doctor gachet who came to his bedside on a Sunday night and dressed his wound. Nevertheless, Artaud had a manic intuition that Dr. gachet was somehow the cause of Van Gogh’s death. Is there any truth to Artaud’s theory, or can it be dismissed as the distorted view of a man who had himself been mistreated by doctors?

“Van Gogh did not committ suicide in a fit of madness, in dread of

not succeeding, on the contrary, he had just succeeded, and

discovered what he was and who he was, when the collective

consciousness of society, to punish him for escaping from its

clutches, suicided him.

It was not because of himself, because of the disease of his own

madness, that van Gogh abandoned his life.

It was under the pressure of the evil influence, two days before

his death, of Dr. Gachet, a so-called psychiatrist, which was the

direct, effective, and sufficient cause of his death.”

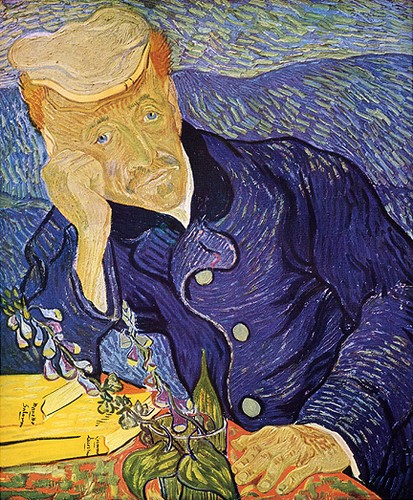

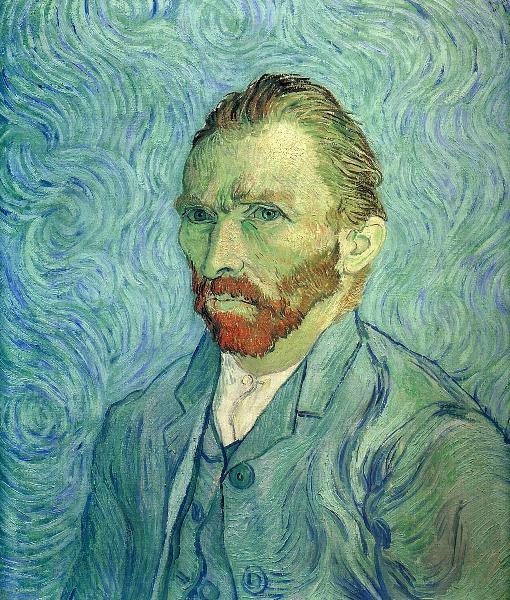

"Van Gogh left the clinic in Saint Remy to travel to Auvers to be treated by the doctor. The two became friends though van Gogh described Gachet as “sicker than I am”. In the end, van Gogh did not take his friend's advice, continued into his demise and would soon commit suicide while under the doctor’s care. Gachet seems sad in the portrait, leaning on his hand with a melancholy expression. It is said that the foxglove plant in Gachet’s hand suggests he was treating Vincent with the plant’s derivative digitalis. This drug is known to cause “yellow vision” linking the plant and drug as having a direct effect on van Gogh’s work, namely the sunflower series. The portrait fetched over $80 million in 1990, which was the most paid in history for a painting until Picasso’s “Boy with Pipe” shattered the record."

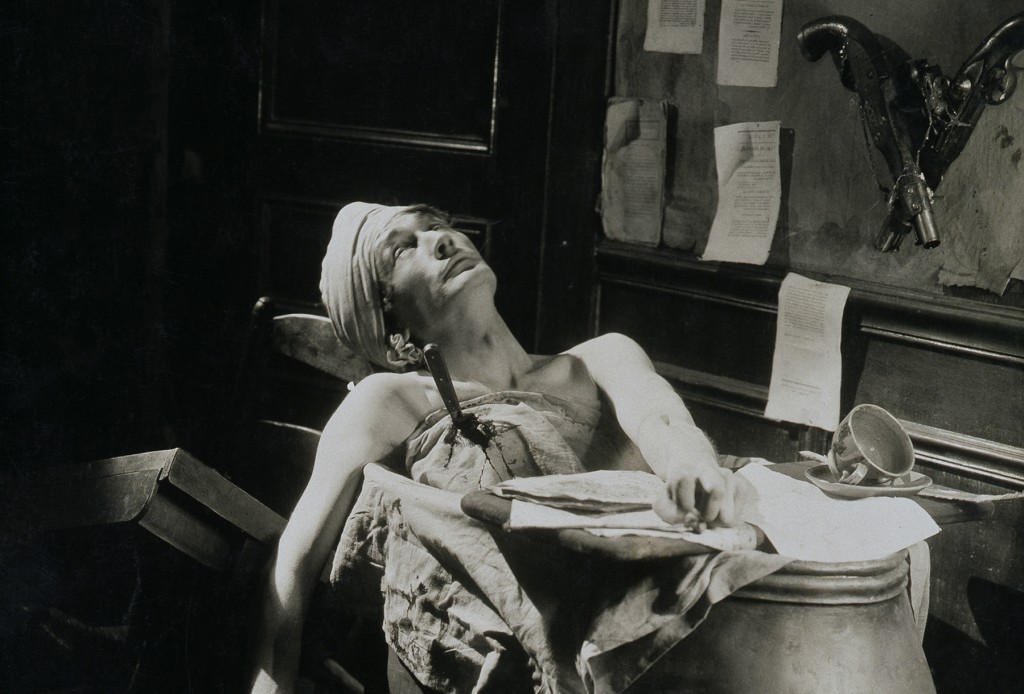

In 1888 Van Gogh was voluntarily committed to an asylum as the result of a vilent scene with Gauguin and the partial mutiliation of his left ear. His brother, Theo, arranged his admission to the sanitarium of Saint- Paul -de Mausole on the outskirts of Saint-Remy-de-Provence, an asylum described as a ” private establishment devoted to the treatment of the insane of both sexes.” In his letters to his brother, Vincent described the director , Dr. Peyron, as a gouty little widower who wore dark glasses; the treatment he used was based on hydrotherapy, and Vincent had many sessions in the bathtub during the year he spent in Dr. Peyron’s institution.

Vincent started working again at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole. First he painted what he saw framed in the window of his cell, without the bars. In July he had a fit, and Dr. Peyron took away his brushes. Vincent asked his brother to tell Dr. Peyron that painting was necessary for him. When he improved, he was allowed to paint in the garden, surrounded by onlooking inmates, and then in the countryside, accompanied by a guard. The periods of work were interrupted by fits and other forms of erratic behavior. Once, when the guard was walking behind him, Vincent turned around and kicked him in the stomach. Then he apologized, saying he thought the Arles police were after him. Dr. Peyron, in his report on Van Gogh, wrote: ” He tried on several occasions to poison himself, either by swallowing the oil color he needed for painting, or by drinking kerosene which he stole from the boy when he was filling the lamps”.

"Manifesto in a Clear Language by Antonin Artaud "I destroy because for me everything that proceeds from reason is untrustworthy. I believe only in the evidence of what stirs my marrow, not in the evidence of what addresses itself to my reason. I have found levels in the realm of the nerve. I now feel capable of evaluating the evidence. There is for me an evidence in the realm of pure flesh which has nothing to do with the evidence of reason. The eternal conflict between reason and the heart is decided in my very flesh, but in my flesh irrigated by nerves..."

One interpretation of Vincent’s fits at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole; that they were connected to events in Theo’s life- was advanced in 1953 by the French psychoanalyst Charles Mauron. Theo, who was working in Paris for the art gallery of Boussod and Valadon, had become engaged to a girl named Joanna Bonger. In the year that Vincent spent confined, Theo married Joanna and had a son by her, whom he named after his brother. Mauron established that the dates of Vincent,s fits closely followed the arrival of letters from Theo announcing his marriage and the birth of his son.

Mauron’s explanation was that Vincent, who was totally dependent on Theo financially, had formulated the following unconscious analysis: Theo is getting married, and it is right that he should devote himself completely to his wife and child. But he is diverting part of his resources from his family to keep me going, and part of his affection in support of me. This is not right, and I must not allow this situation to continue. But how can I change it, except by withdrawing from Theo’s life by destroying myself?

Vincent had one crisis in January, 1890, and another in February, which lasted two months. He wrote that he could not improve in the asylum, surrounded as he was by madmen. Their madness, he felt , was contagious. He asked Theo to find some other place where he might go, and Theo went to the painter Camille Pisarro for advice. Pisarro knew a doctor who specialized in nervous ailments and was friendly with the impressionist group. The doctor, Paul-Ferdinand Gachet, had a house in the pleasant village of Auvers-sur-Oise where he had collected the works of Cezanne, Renoir, Manet, and other new painters. He himself painted under the pseudonym of Van Ryssel. Just the man, thought Pisarro, who would understand Vincent’s problems.

Vincent was delighted at the prospect of leaving the asylum and of being treated by a doctor, who, without even having met him, already thought he could cure his condition. He urged Theo to press for his release. Vincent left Saint-Paul-de-Mausole on may 16 and went to the nearby town of Tarascon to take the train to Paris. Theo, so concerned about Vincent’s traveling alone that he had spent a sleepless night, fetched him the next day at the Gare de Lyon and took him home to meet his infant nephew and namesake and his sister-in-law. Joanna was surprised at how healthy and vigorous he looked. She thought he was in better condition than Theo.

"At Documents you can see Germaine Dulac’s film The Seashell and the Clerygman. Also featured are a text of Antonin Artaud who wrote the screenplay in which he writes favorably about Dulac’s adaptation and an account which fuses various testimonies of the film’s premiere with the surrealists protesting violently against the film. The post closes with the following question: What happened between the glowing praise Artaud wrote on October 29th, 1927 and the premiere on February 2, 1928? Did Artaud see the film die on the cutting room floor? Or did the Surrealists hijack the premiere, did they take advantage of some critical remarks Artaud might have made about the film to create a row? Artaud’s later remarks on the film would remain contradictory. In a letter to Jean Paulhan, written in 1932, he expressed his conviction that Seashell was a better film than both L’Age d’Or and Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet and that they borrowed heavily from it. On the other hand he felt disenchanted that he was kept from participating in its filmmaking process...."

Vincent wanted to leave for Auvers as soon as possible-Paris made him nervous- and, on may 19, with a letter of introduction from Theo, he arrived at Dr. Gachet’s house, walking up the twenty-two front steps and waiting in a drawing room crowded with paintings, bric-a-brac, and black antique furniture. Soon, Dr. Gachet appeared, a short man of sixty-two with a long nose, a prominent chin, extraordinarily bright and darting eyes, and stiff red hair that stuck out from his head like the bristles in a hairbrush.

Dr. Gachet told Vincent not to think about his illness, to work quietly, keep regular hours, and eat moderately. He was sanguine about Vincent’s chances of recovery and prescribed no medication. He sent the patient to a nearby boarding house, but Vincent quickly found a more modest establishment on the Place de la Mairie, Chez Ravoux, where room and board was only three francs fifty a day.

Two days later, Vincent wrote Theo and Jo: ”I have seen Dr. Gachet who gives me the impression of being rather eccentric, but his experience as a doctor must keep him balanced enough to combat the nervous trouble from which he certainly seems to be suffering at least as seriously as I …The impression I got of him was not unfavorable. When he spoke of Belgium and the days of the old painters, his grief-hardened face grew smiling again, and I really think that I shall go on being friends with him and that I shall do his portrait. Then he said I must work boldly on, and not think at all of what went wrong with me.”

In the intervals between his fits, Vincent was completely lucid, and in his letters to Theo he showed a remarkable understanding of the personalities of others as well as his own. He was not in the habit of questioning the mental stability of the people he met, for he knew how precarious the balance of the mind could be. Still, after a single meeting with Dr. Gachet, Vincent was convinced that he, too, was unbalanced.

What was there about Gachet to justify Vincent’s judgment? Certainly, he was no ordinary doctor. Born in Lille in 1828, he was an early convert to homeopathy, the school of medicine that believes the cure of a disease is effected by minute doses of drugs capable of inducing symptoms similar to those of the disease being treated. He was outspoken in his low opinion of surgeons and organic medicine, but he completed his studies at the school of medicine in Montpellier, writing his thesis on melancholy. He then practiced in Paris, where he befriended painters, particularly the impressionists. Cezanne was his house guest in Auvers, and Manet, Pissarro , and Renoir were all close friends of his.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS