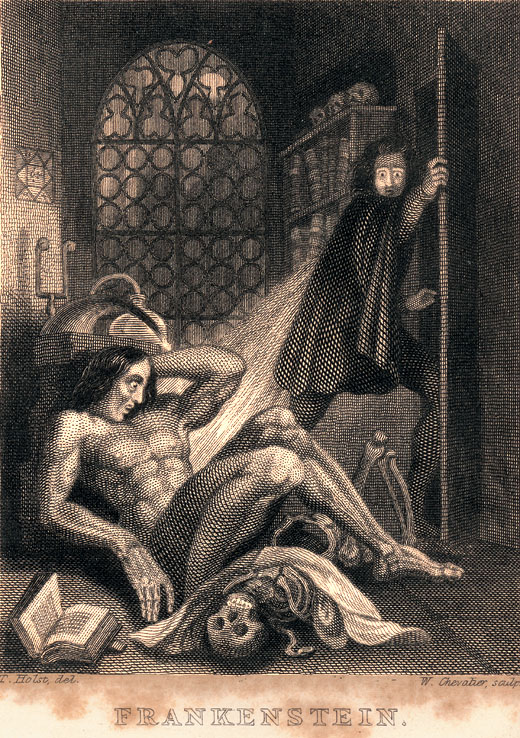

The popular culture’s notion that geniuses were crazy certainly received support from the excesses of many of the Romantic artists of the nineteenth century, who had their share of obsessive, manic, and ecstatic behaviors. Further, the “mad scientist” in literature ,such as Shelley’s Dr. Frankenstein, often reinforced the idea that scientists were fairly megalomaniacal and unstable people. Emile Zola added fuel to the fire by actually inviting fifteen psychologists to examine him, and not unsurprisingly he agreed with their conclusion that he was “slightly neurotic.” He and other creative people actually agreed to accept the “crazy” label, perhaps because they did not see it as being as much of a stigma as it is seen today, as well asa means of augmenting their notoriety.

"If, that is, you believe that Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley really was the genius behind one of our most enduring tales of existential horror. Almost from the moment that it was published anonymously on New Year's Day 1818, Frankenstein had readers and critics arguing over its origins. Early rumor held that it wasn't Mary Shelley but her husband, the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who deserved the credit. (Or the blame; some early readers were outraged by the novel's idea that a man could play God and create life.) Even after the couple confirmed Mary's authorship and her name appeared on new editions in 1823 and 1831, some critics held on to the idea that Percy was the guiding spirit behind Frankenstein."

Ultimately Goethe defines the term genius as a martyred madman, driven by nature’s divine will via passion in his fierce debate with Albert. To Goethe, genius is free, noble, virtuous, and unexpected:

“Passion. Inebriation. Madness. You respectable ones stand there so calmly, without any sense of participation, upbraid the drunkard, abhor the madman, pass them by like the priest and thank Godlike the Pharisees that He did not make you one of these! I have been drunk more than once, and my passion often borders on madness, and I regret neither. Because, in my own way, I have learned to understand that all exceptional people who have created something great, something that seemed impossible, have to be decried as drunkards or madmen. And I find it intolerable, even our daily life, to hear it said of almost everyone who manages to do something that is free, noble, and unexpected: he is a drunkard, he is a fool.”

"A highlight of the Roman carnival was the race of small horses from wild stock—called Barbary after their North African origin—down the mile-long Corso, from the Piazza del Popolo to the Piazza Venezia. Many writers and artists were attracted by the colorful event and sometimes appalled by the cruelty of the populace. Weighted, spiked balls were attached by cords to the horses to spur the animals as they moved. Vernet was a close associate of Gericault, and he must have known the many studies the artist made in Rome in 1817 for a painting of the race. Vernet's own composition of 1820 was bought by an influential collector, the duc de Blacas, who was the French ambassador to Rome during Vernet's stay.

The cult of celebrity.The artistic temperament. The troubled genius.The exploration of contradictory co-exiting elements in human nature. It seemed to begin with the Grand Tour and the discovery of the mediterranean; and of death, romance, light, passion, roast game birds, love, peril, beauty, pleasure, art, the natives, happiness, and everything else: by the nineteenth century Romantics.

Although we think we live in the age of celebrity, it’s been quite a while in coming. When we think of enthralled fans and groupies, media accounts of scandalous behavior and all manner of transgression, we inevitably think of rock stars and tabloids, but the model for all this was set nearly 200 years ago with the defining figure of Lord Byron and other romantics who were discovering the pagan myths, the cult of dionysus and its odd and discomfiting relationship with the Christian gospels.

…Until the mid-1700s, ( Fred ) Inglis explains, kings, cardinals, and other leading citizens enjoyed “renown” rather than celebrity. “Public recognition,” the author writes, “was not so much of the man himself as of the significance of his actions for the society.” Queens qualified, too. Elizabeth I was renowned as a monarch, not a mere personality; her fame was “conferred by her people on behalf of God and England.” The rise of urban democracy in London “made fame a more transitory reward and changed public acclaim from an expression of devotion into one of celebrity.”

Fred Inglis:But as the lighting grew ever brighter and the ways of keeping track multiplied, so did the burden of maintaining the image that encapsulated celebrity. If we think we live in a spa culture, fixated on looks and dieting, consider this from two centuries back: "Byron was going bald, was ill more frequently as he paid the price for pretending eternal youth, put on fat and dieted it ferociously away, went riding hell for leather in torrential rain, kept up hellfire drinking to match, and paid the price in doctors' bills."

Keats, Goethe, Byron, Shelley, Corot, Gericault, Stendhal, Turner and others were not the first artists from the north to make the pilgrimage to the Mediterranean; Milton, Durer, Handel and Mozart were among their predecessors. But the romantics were the first to roam the region more or less at will without worrying about their safety. In the century in which privilege gave way to talent, the artist could exercise his geographic as well as his social mobility.

Romantics like Byron- who found Catholicism "elegant" - loved ecclesiastical pageantry as much as they did the pagan antiquities. "Being well-born was not enough for this man; he went on to command the attraction of the whole world. Women —commoners as well as aristocratic— swooned, pursued, and desired him. While some men envied him, others appreciated his charisma and rebellious attitude towards art, politics, and injustice. From his first speech in the House of Lords, to his death (fighting on the side of the Greeks and against the Turks), he lived with passion and pride and arrogance. In his work his voice is at times indistinguishable from

t of the heroes he sang about. His projected melancholy permeated his generation."Though he did not want to be known as a “romantic” , it may have been Goethe, out of all the artists, who experienced this inner revolution of the mediterranean at its more profound levels and he may have been psychologically the best prepared for it. He had been dreaming of Italy for years, and his acute longing was expressed in his novel “Wilhelm Meister” , begun some years before his escape: Mignon, a child from the south, sings the famous “lied” that expresses Goethe’s yearning.

Do you know the land where the lemons grow,

Where, in the dark trees the gold oranges glow,

A soft wind blows in the blue sky,

The myrtle silent and the laurel high—

Do you know it well? Down there! Down there!

I would with you, oh my lover, repair

… “Successful merchants and their wives had free time to gossip in elaborate pleasure gardens and attend the burgeoning theater. Artists, composers, and, above all, actors gained recognition for the elevated diversions they offered. They were commoners whose private lives became intermingled with their public accomplishments. It did not go unnoticed among a new class of theatrical impresarios that scandal, especially sexual misdemeanors, enhanced a star’s glamour quotient. Actress Sarah Siddons elicited audience tears for her stage performances in the 1770s. A friend of Queen Charlotte, she was rumored to be the mistress of not only a well-known painter but a fencing master, too. In a gesture familiar to devotees of Angelina Jolie and Madonna, Siddons received visitors while in the midst of what Inglis calls the “ostentatious mothering of her children”: using her foot to rock the crib of one while holding another to her breast. Fans simultaneously adored and deplored her, a love-hate dynamic that still defines the culture of celebrity today….

Sarah Siddons by Thomas Gainsborough " Siddons may have succeeded in using the motherhood ideal to mask the real nature of her daily life (endless work as an actress, with other people caring for her children) to her contemporaries. This ideal may have shown other actresses how they could present themselves so as to prevent the public from regarding them as (in effect) prostitutes available to rich men who wanted to “protect” them (abduct, rape, or support). This may have helped the English actresses after her to gain respectability. Still, the hard reality was the only husband Sarah Siddons could attract and hold was someone who himself had no connections or means to support her and their family. She was lucky he was not already married to someone else (bigamy seems to have been common) and was a decent loyal partner. Having the children and acting out ideal motherhood is not what protected her; had her children been illegitimate they were in danger of being treated badly. It may be that like Dora Jordan, Sarah Siddons lived to act, but this kind of passionate idealism was not brought out in the session. Instead Siddons was shown as a calculating self-presenter. In Life Mask Emma Donoghue dramatized her as a woman who played the sort of role where she kept herself above everyone else, who was probably uncomfortable in public situations off the stage. In one of the few writings by her that have survived, we see how getting others to treat her with dignity was intensely important to her way of getting through life."

One day in the summer of 1786 Goethe himself could no longer contain his wanderlust. Without telling anyone except his valet, he left for Rome. The beneficiary of his Mediterranean experience was “Faust”, the most important book of the romantic age; the romantic conflict of the divided soul and the contradictions between great knowledge as a harbinger of sin in equal proportion; with a species of pagan blind faith as the road to salvation ni a pot- pourri of mutual exclusives often at cross purposes which Christianity is unequipped to resolve.

“In a certain way, Goethe did a huge favor for capitalism. He increased desire for extraordinary individualism. Werther wore funny clothes, he went his own way, and he killed himself for love, the ultimate act of self-will. Werther was so popular that suicide rates increased among young people who read the work, and in 1974 a sociologist David Phillips coined the term based on this phenomena “the Werther effect.” This is ironic considering that Goethe meant to spread the gospel of the individual. Instead, he noticed imitators- people wearing Werther fashions and committing suicide. This had to be confusing for him.”

Mark Beech:If you’re looking for someone to blame for Lady Gaga, Madonna and Britney Spears, go back to 19th-century actress Sarah Bernhardt, who made headlines with her love life and traveled with a pet lynx. Celebrity painters such as Andy Warhol are the heirs of Joshua Reynolds; Tiger Woods and Richard Gere follow Lord Byron. This is the view of writer Fred Inglis, who links all these, Princess Diana, J.P. Morgan and Marilyn Monroe in his lively book, “A Short History of Celebrity.”

As for the other great Faustian leitmotif, the Eternal Feminine that drives him ever onward, it was while drumming out the hexameter’s beat on Faustina’s back that Goethe was introduced to the erotic world Faust encounters in helen of Troy. Helen embodies the same ideal of physical beauty and Mediterranean passion that, in another of the “Roman Elegies” , is identified with the Goddess Opportunity”:

Once she appeared to me, too: a dark-skinned girl, tumbling

Over her forehead the hair down in waves heavy and dark.

Round about a delicate neck curled short little ringlets;

Up from the crown of her head crinkled the unbraided hair.

When she dashed by me I seized her, mistaking her not. Lovingly

Kiss and embrace she returned, knowing and teaching me how.

O how enraptured I was! Ah, say now no more. It’s a bygone.

But, O pigtails of Rome, still I’m entrammled in you.

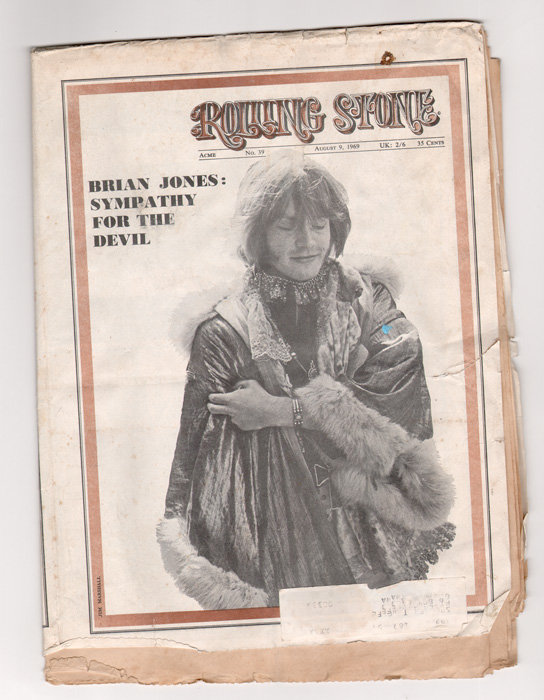

Art Chantry:this brian jones cover is a particularly audacious intro to this bizarre sub-genre of magazine covers. i men, look at this thing. from the infamous stoned monterey pop festival photo by jim marshall (notice that his eyes are closed? clever, eh? it's almost as if he's already dead!!!! snort.) to the color scheme (chocolate brown and black ink. mourning colors.) the cape brian is wearing in the photo looks like a funeral shroud. these bonehead choices are no accident. even the astonishing headline "brian jones: sympathy for the devil" pulls no punches when it goes for that knockout "national enquirer" style exploitation of the tragedy. art director robert kingsbury (rolling stone's original art director, i believe) was very much a product of his times and was no slouch when jann wenner (rhymes with 'yawn') went for that mass market top dollar "let's make a lotta money, boyz!" approach to what they laughingly referred to as "journalism" back then. come to think of it, that magazine hasn'e changed a whit since then, either.

This dark-haired, joy giving, full breasted goddess is the tutelary deity of the Mediterranean, and has much to do with the continuing popularity of the place. It is not unusual for a romantic poet to confess that he had never known what real passion was until he experienced it in her arms. Perhaps part of her reputation for voluptuousness is pure wishful thinking, though of a self-fulfilling kind: the northern Calvinist, with his guilt ridden notions of sex, projects his repressed fantasies onto the women of this sunburned land, whose very climate is supposed to make them more hot-blooded and elemental than the girls he knows at home. The south, in his eyes, becomes synonymous with sultry females.

When Byron settled in Italy he learned that for a married woman to have a lover, a so called ” cicibeo” or “cavaliere servente” , was the order of the day. “The reason is, that they marry for the parents, and love for themselves.” Once started, they tend to become very good at it. “Love is not the same dull, cold, calculating feeling here as in the North… it is a want, a necessity… they begin to love earlier, and feel the passion later than the Northern people.”

Yet the system was not as sexually liberating as it seemed. When Byron became the acknowledged “cicibeo” of the Countess Guiccioli, a beautiful nineteen- year- old who had married a nobleman of sixty, he discovered that the lover was supposed to be more loyal than any husband would ever be.

Byron was gallant about it, but he felt vaguely trapped. During his first year in Venice, he had kept mistresses and run through the available women like a deck of cards, entertaining as many as nine at a time. “it is a very good place for women,” he decided. “There is a naivete about them which is very winning, and the romance of the place is a mighty adjunct…” He was, however, inclined to be far less rapturous than Goethe in appraising his love objects. “She plagues me less than any woman I ever met with,” is the highest compliment he can think to pay his first Italian mistress.

With his schoolboy penchant for boasting of his conquests, Byron may qualify as a material witness, but hardly as an insightful observer of the scene. It is Stendhal who should be consulted on the more subtle aspects of love in the Mediterranean-Stendhal , for whom happiness is a coefficient of the south, and the art of living virtually an Italian monopoly. unlike most of the other expatriates, he is not content merely to transplant his native habits to this foreign land; he creates a whole new way of life that will give him an insider’s taste of the local pleasures. He becomes an ardent opera lover, for one thing: happiness, for Stendhal , is neither a museum nor a bordello but a theatre. “If i ever amuse myself by describing how my character was formed by the events of my youth, the “Teatro della Scala” will be in the front rank.”

Stendhal’s first great love, Angiola Pietragrua, was a raven haired beauty whose “grace filled with voluptuousness” summed up the very qualities he loved about Italy. He saw her first when, not yet eighteen, he came riding into Milan at the tag end of the Napoleon campaign of 1800- but he did not manage to sleep with her until 1811, when he returned to Italy on military leave and confirmed his impression that ” love under such skies is a pure delight; no other land knows aught but the palest imitation.”

ADDENDUM:

“Of course, there are models of genius which suggest that it is not an innate or inherent quality, and that it is just a label which society selectively applies according to exclusionary, culturally-derived criteria. People are said to be “geniuses” because they say things which people want to hear. Under this model of genius, the supposed rarity of genius is to provide an ideological guarantee for the power of knowledge elites or experts. The interesting thing about biological models of genius are that they treat it as a fixed, measurable quantity – present only in a few people, and some of those people have greater shares than others – and ignore the possibility that it may be a conferred title rather than a recognition of ability. The fact is that the term genius itself changes in history: in the Renaissance, men of genius were noted for their adherence to the imitiatio-ideal (they were able to imitate other works of art with great accuracy) whereas in the Enlightenment the notion of genius came to refer more to rational ability. Following the Enlightenment – in the Romantic period especially – genius came to be focused on originality, irrationality, and transgressiveness. It is during the Romantic period, not unsurprisingly, that people begin to most strongly associate genius with madness. However, as Becker notes, when the social norms regarding innovation in the West change, the aspects of genius that seemed crazy are now perceived as less threatening.”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS