Pick your protest.Is this wave of political activism, from Black Bloc to Tea Party different from past manifestations? Every era has unique twists, but they are each not as different as you may think. This time it’s different?… Natalie Zemon Davis: I define tradition as ways of thinking, doing, and feeling that a social group inherits from the past. Some would prefer to say “believes it has inherited from the past”, for, as Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger famously argued, many political traditions, especially those associated with nationalism, are “invented.”

"In an interview with AOL News, Khatib explained how the idea to impersonate Na’vi, the movie’s subjugated blue-skinned race, sprouted in Europe. There, a Palestinian author and documentary filmmaker named Liana Badr was so moved by the film’s similarity to the Palestinian experience in the West Bank that she recommended it to Khatib. Unfortunately, Khatib and his fellow villagers couldn’t just rush off and catch the next matinee – there are no cinemas in their area, he said. Instead, an activist snagged a bootlegged copy for them last Sunday."

I would rather go beyond the simple dichotomy of “invented” traditions and “real” traditions to suggest a different model. All traditions get handed down with some conflicts about their interpretation: I can’t think of a single counter-example. Even the most ecstatic religious movement or radical political movement generates disagreements by the end of the first generation about how to interpret its founding ideas or how to fulfil its hopes.

So I would turn Hannah Arendt’s “tradition” and “thread which safely guided us” into “traditions” and “entangled threads”, and suggest that if traditions lay out a space beyond which people in a community are not supposed to stray, that within that space there can be different paths and room to dig deeper – even to find something new while perhaps labeling it traditional. Innovations that expand the boundaries or redraw them in a different shape usually take something from what went before….

Pictured left to right: Kelly Moore, Stephen Duncombe, Sydney Railla-Duncombe (aged 4 months), Bob Lesko. The New York Bill of Rights Defense Campaign organized the effort.

People around the world are now mobilizing icons and myths from popular culture as resources for political speech, which can be called “Avatar activism ” Its one symbol fits almost all. Pop culture has become the basis for a participatory approach to world activism. This stretches from Harry Potter fans for gay rights in the U.S., to Palestinians painting themselves Na’vi blue to resemble the Na’vi from James Cameron’s “Avatar”. Even relatively apolitical critics for local newspapers recognized that “Avatar” spoke to contemporary political concerns.

"Five Palestinian, Israeli and international activists painted themselves blue to resemble the Na’vi from James Cameron’s blockbuster Avatar in February, and marched through the occupied village of Bil’in. The Israeli military used tear gas and sound bombs on the azure-skinned protesters, who wore traditional kaffiyehs with their Na’vi tails and pointy ears. The camcorder footage of the incident was juxtaposed with borrowed shots from the film and circulated on YouTube. We hear the movie characters proclaim: “We will show the Sky People that they cannot take whatever they want! This, this is our land!”

The critiques for “Avatar” were launched by land, sea and air; where left is left and right is right and never the twain shall meet. There was something for everyone to pick a bone about: new age belief, promotion of smoking, anti-militaristic, anti-human and racist messages….

Conservative U.S. publications like National Review saw the film as anti-American, Military and capitalist; and many on the left ridiculed the film’s contradictory critique of colonialism, white supremacy and embrace of white liberal guilt fantasies. The Vatican, likely spoke for most organized religion when they stated: ” The Vatican newspaper and radio station voiced their opinion about “Avatar,” calling the film simplistic and sappy with awe-inspiring special effects. Outside of that, the Vatican wasn’t happy that the movie presented nature as something to worship.

"Rights activists, including actors from James Cameron’s film Avatar that highlights the threat to environment, held a protest outside the venue of the annual general meeting of the mining company Vedanta here on Wednesday against its controversial plans to mine tribal land in Orissa regarded sacred by Dongria Konds. Some protesters wore blue face paint in an echo of Avatar’s portrayal of the destruction of an “alien’’ tribe."

“[The film] gets bogged down by a spiritualism linked to the worship of nature,” they said. “[It] cleverly winks at all those pseudo-doctrines that turn ecology into the religion of the millennium. Nature is no longer a creation to defend, but a divinity to worship.”This statement reflects Pope Benedict XVI’s views on the dangers of turning nature into a “new divinity.” He has often spoken about the need to protect the environment, earning the nickname of “green pope.” But he al

as balanced that call with a warning against turning environmentalism into neo-paganism.

The demonstrators also donned long hair and loincloths Friday for the weekly protest against the barrier near the village of Bilin.

Still, encouraging a healthy skepticism toward the production of popular mythologies are better than puritan critics of the Frankfurt School variety who lamely see popular culture as trivial and meaningless, offering only distractions from our real-world problems. The meaning of a popular film such as “Avatar” lies at the intersection between what the author wants to say and how the audience deploys his creation for their own communicative purposes.

Ultimately, the criticisms of the film are irrelevant, and to some degree its artistic merit as well. It is “successful” as a universal vehicle of appropriation making the numerous criticisms subordinate to how the imagery can be distorted to serve other means. Conservative critics such as from The Weekly Standard worried that Avatar might foster anti-Americanism, but as the image of the Na’vi has been taken up by protest groups in many parts of the world, the myth has been rewritten to focus on local embodiments of the military-industrial complex. In Bil’in, the focus was on the Israeli army; in China, on indigenous people against the Beijing government; in Brazil, the Amazonian Indians against logging companies and so on. The iconography becomes generic.

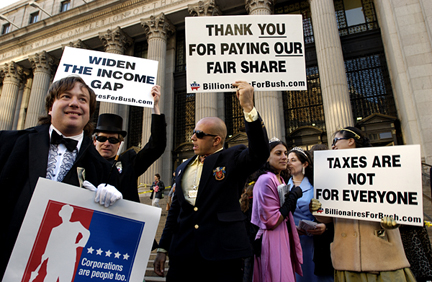

Auctioning Social Security during Bush's re-coronation in DC. And hey, when's that global warming going to kick in?

What is common is that for example,The Bil’in protesters, of which half were Israeli, recognized potential parallels between the Na’vi struggles to defend their Eden against the Sky People and their own attempts to regain lands they feel were unjustly taken from them. “Avatar’s” larger-than-life imagery, recognized worldwide thanks to the Hollywood brand and marketing prowess, offered the demonstrators an empowered image of their own struggles. The sight of a blue-skinned alien writhing in the dust and choking on tear gas shocked many into paying attention to messages we often ignore.

"CHICAGO - In her police mug shot, the doe-eyed cartoon heroine with the bowl haircut has a black eye, battered lip and bloody nose. Dora the Explorer's alleged crime? "Illegal Border Crossing Resisting Arrest." The doctored picture, one of several circulating widely in the aftermath of Arizona's controversial new immigration law, may seem harmless, ridiculous or even tasteless. But experts say the pictures and the rhetoric surrounding them online, in newspapers and at public rallies, reveal some Americans' attitudes about race, immigrants and where some of immigration reform debate may be headed. "Dora is kind of like a blank screen onto which people can project their thoughts and feelings about Latinos," said Erynn Masi de Casanova, a sociology professor at the University of Cincinnati. "They feel like they can say negative things because she's only a cartoon character."

The “Avatar” activists are not reinventing a form of protest, but rather plumbing an old language within a digital communication context that has been employed in popular protest before. The cultural historian Natalie Zemon Davis reminds us in her classic essay “Women on Top” that protesters in early modern Europe often masked their identity through dressing as peoples real (the Moors) or imagined (the Amazons) seen as a threat to the civilized order. The good citizens of Boston continued this tradition in the New World when they dressed as native Americans to dump tea in the harbour. And African-Americans in New Orleans formed their own Mardi Gras Indian tribes, taking imagery from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, to signify their own struggles for respect and dignity.

Like Martin Luther King forty years before them, Billionaires lead a heroic march for their rights — to buy the president.

“I tried to show how an extraordinary imposture was a version of identity formation, of “self-fashioning” as Montaigne named it, both among peasants and among the judges and other persons of wealth and rank who read Jean de Coras’s book by the thousands. Influenced by thinking about cinematic narration, I decided to tell the prose story twice, first as it unfolded and was seen at each stage in the village, then as recounted by the storytellers: Judge de Coras, a young lawyer in the court, Montaigne and others. I hoped to suggest to readers some of the parallels between establishing what was true about identity and establishing what was true about history.” ( Zemon Davis )

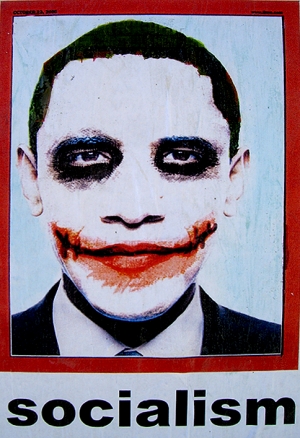

"Tea Partiers claim that there is nothing wrong, because it is a parody of the Joker from the film The Dark Knight. While I would consider this an effective photo from the lens of a Tea Partier, there's still a problem with the picture. Historically blackface and whiteface have racist contexts. It was a way to expose and cement racist ideals in the early days of film. black characters would put on black-face to make them appear darker, to accentuate the point. In the case of whiteface, black characters would wear it to appear white or lighter skinned. This practice was ended in film by the 1960s. While I'm pretty sure that initially no one thought about the context of blackface on black characters in film, but now that they know about it, they still use this image. I see this image as pretty offensive and inconsiderate."

Without painting themselves blue, people like the Indian writer Arundhati Roy and the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek have used discussions about “Avatar” to call attention to the plight of the Dongria Kondh peoples of India, who have just won a battle with their government over access to traditional territories rich in bauxite. It turns out that the United States isn’t the only evil empire left on Planet Earth. Leftists worry that the focus on white human protagonists gives an easy point of identification. But protesters just want to be in the blue skins of the Na’vi.

In recent years, however, is seems that historians have become more comfortable with the notion that identity can be contested, conflicted, and multiple, that it can be embedded in and the product of social and cultural structures, and yet still exist as a meaningful topic of historical exploration. This has allowed the re-entry of biography into historical scholarship. In her Women on the Margins: Three Seventeenth-Century Lives, Natalie Zemon Davis moved away from the tendency to see collective biography as a mirror of group identity, writing of her three subjects that the “variant patterns [of their lives] alert us to mobility, mixture, and contention in European cultures.”

Stephen Duncombe, a media theorist, has argued that the American left has adopted a rationalist language that can seem cold and exclusionary, speaking to the head not the heart. But by rejecting the wonkish vocabulary of most policy discourse, it could draw emotional power from its engagement with stories that already matter to a mass public. Mr. Duncombe cites an activist group that called itself Billionaires for Bush, whose members posed as mega-tycoons straight out of a Monopoly game, to call attention to the corporate interests shaping Republican positions. He might have been writing about protesters painting themselves blue or Twitter users turning their icons green in solidarity with the Iranian opposition movement.

Billionaires thank ordinary New Yorkers for taking on a greater tax burden to put millions more in our pockets. Photo by Fred Askew

When a community linked by language and/or common experiences, institutions, and customs has its history (or histories) rewritten by a conqueror, then it’s not surprising that a national past will be affirmed in resistance. Osip Mandelstam wrote movingly of such a loss: “Your backbone is broken,/ My beautiful, pitiful century./ With an idiot’s harsh and feeble grin you look behind.”

Duncombe:"It’s a close shot of a handful of young protesters standing in the middle of the street. To the left is a row of attractive women, in their early twenties at the oldest, dressed with that careless elegance that Parisian women are justly famous for. They hold red flags. A few of the flag poles are thrust forward at forty-five degree angles, a few more pointed back. Behind them, with their backs to the women and facing the other direction are two young men. They wear dark jackets, black leather in the case of the man in the foreground, and both have megaphones raised to their lips. It’s a striking image – both aesthetically and historically -- which is no doubt why the fashion designer’s advertising agency selected it. It bespeaks hip rebellion, which today, of course, is the lingua franca of mass consumption. It is the alchemy of advertising: buy this product and you will magically become someone who could care less about things like products. "

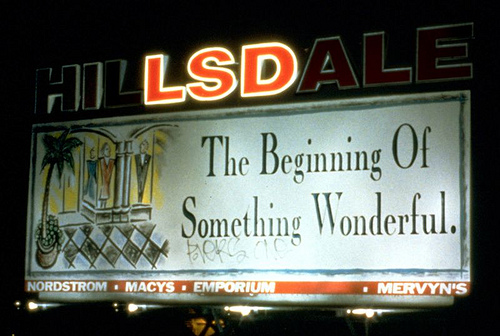

There are many recent examples of groups repurposing pop culture toward social justice. It is a participatory culture and everyone from spoofers, to corporations to causes for social justice and legitimate grievances are getting involved. In contrast to mass media’s spectator culture, digital media has allowed many more consumers to take media into their own hands, hijacking culture for their own purposes, or “culture jamming” and doing digitally what the Billboard Liberation Front does for public space. Shared narratives provide the foundation for strong social networks, generating spaces where ideas get discussed, knowledge gets produced, and culture gets created.

"The advertisement is currently at liberty and it seems to have successfully readjusted to public life. However, the billboard will remain under surveillance by department staff to prevent recidivism and any potential lapse into its prior criminal behavior"

In this process, fans are acquiring skills and building a grassroots infrastructure for sharing their perspectives on the world. Much as young people growing up in a hunting society may play with bows and arrows, young people coming of age in an information society play with information, imagery and collage in a pastiche form of creation and transmission.

Andrew Slack, a director of an NGO called the Harry Potter Alliance, describes this process as “cultural acupuncture,” suggesting that his organization has identified a vital pressure point in the popular imagination and sought to link it to larger social concerns. The HPA has mobilized more than 100,000 young people worldwide to participate in campaigns against genocide in Africa; in support of workers’ rights and gay marriage; to raise money for disaster relief in Haiti; to call attention to media concentration and many other causes. J.K. Rowling’s creation, Harry Potter, Mr. Slack argues, realized that the government and the media were lying to the public in order to mask evil, organized his classmates to form Dumbledore’s Army and went out to change the world. All this may mobilize young people who have traditionally felt excluded or marginalized from the political process.

This new style of activism doesn’t require us to paint ourselves blue; it does ask that we think in creative ways about the iconography that comes to us through every available media channel. Consider the ways that Dora the Explorer, the Latina girl at the centre of a popular American public television series, has been deployed by both the right and the left to dramatize the likely consequences of Arizona’s new immigration law; or how the U.S. Tea Party has embraced a mash-up of Obama and the Joker from the batman film, “The Dark Night Returns”, as a recurring image in its battle against health-care reform.

"Nine Tips for Avoiding Arrest: Unfortunately, this activity is illegal, but there are some precautions you can take. 1. Work in daylight hours. It’s far less suspicious. 2. Don’t bring too many people or linger too long. 3. Keep your billboards professional looking. 4. A camera crew can actually alleviate suspicion. Tell the police, “We’re making a video.” 5. Create work orders using the billboard company’s logo in advance. Include your own phone number. Put a message on your machine like, “You have reached Outdoor Systems. Please call back during business hours.” Also consider having a friend wait by the phone to play your boss."

Such analogies don’t capture the complexities of these policy debates, just as we can’t reduce the distinctions between American political parties to the differences between elephants and donkeys, icons from an earlier decade’s political cartoonists. Such tactics work only if we read these images as metaphors, standing in for something bigger than they can fully express.”Avatar” can’t do justice to the old struggle over the Occupied Territories, and the YouTube video is no substitute for informed discourse about what’s at stake there. Yet their spectacular and participatory performance does provide the emotional energy needed to keep on fighting. And that may direct attention to other resources.

"6. If you are spotted by the police, continue working at the pace of a minimum wage employee of a billboard company. 7. Talk directly to the police in a friendly, unconcerned tone, and have your partners walk off. After all, you just post ‘em for minimum wage and are happy for the diversion provided by the police. 8. If an arrest does occur, it’s better to absorb blame yourself and leave the others to bail you out. 9. If possible, run like hell." Ron English

ADDENDUM: ( Jerome Langguth ) :In Chapter 4 of The Transfiguration of the Commonplace, Danto discusses a number of cases designed to highlight crucial differences between aesthetics and the appreciation of art. In one of these cases, Danto asks us to imagine a group of “sensitive barbarians” who lack the concept of art, but for whom it is possible to discern beauty. Danto explains that his barbarians “do in fact respond to just the things that we would offer as paradigms: to fields of daffodils, to minerals, to peacocks, to glowing iridescent things that appear to have their own light.”i Danto contends, however, that the barbarians would be unable to recognize the characteristic “luminosity” of an old master painting or drawing. Where we would perceive a haunting inner light emanating from Rembrandt’s canvas, the barbarian sees, at most, a pretty or charming thing.ii In order to discern the qualities that the Rembrandt possesses as a work of art, our sensitive barbarians would need to have, at the very least, the concept of an artwork.

Danto further asks us to imagine that these barbarians go on a rampage, during which they take for themselves all of the artworks in “the civilized world” which “happen to have beautiful material counterparts.”iii Danto here provocatively wonders how many of the world’s recognized masterpieces would end up in with the barbarian’s loot. Lacking a concept of art, Danto reasons, the barbarian eye (and ear) would be likely to overlook any art which failed to display its beauty on the surface in a way readilydiscernible to all. That is, the barbarians lack the “cognitive apparatus” to differentiate between a work of art and its identical material counterpart.

Another way of describing the condition of Danto’s sensitive barbarians would be to say that they lack the capacity for what I am calling aesthetic disappointment. Since they are by definition without the concept of an artwork, they would, for example, experience no dismay upon learning that over half of the artworks that they had plundered were not artworks at all, but objects materially indistinguishable from art.

For our unfortunate barbarian brethren there is only one world of aesthetic appreciation: the world of beautiful objects, in which all beauty is on the surface of things. This being so, there is nothing for them to be disappointed about if they discover that an object they are admiring is an ordinary object rather than a work of art. They would simply go right on appreciating the same beauty-making qualities that they had been enjoying before the deception was discovered.

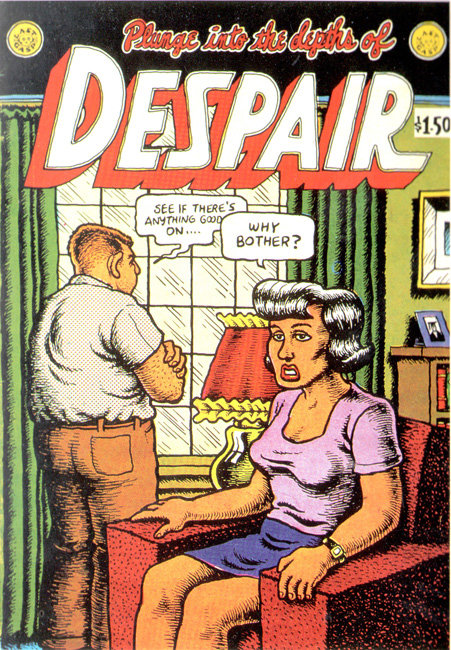

Art Chantry on Crumb. "the guy is about what it's like to be alive, the events, the thought and feelings, the dreams, the fantasies, the detached self- observation, the snide observations. it's the walking breathing fucking puking reality we all share, but it's in his cartooning right there for all of us to identify with. no matter how absurd and silly the 'stories' become, the human experience is still there, thudding along. we all love it. it becomes our shared autobiography somehow. we identify with crumb. he is us, now."An appropriation of the Norman Rockwell middle America zested with the Beat Generation ethos. "

Danto’s barbarian case suggests something important about aesthetic disappointment that is connected to the overall project of The Transfiguration of the Commonplace. What the case makes plain is the point that in order to have an experience of suddenly losing interest in an admired object because it is not a work of art, one would first have to have a set of beliefs tying appreciation of the object to its specific manner of being in the world. Thus one is capable of aesthetic disappointment of the sort under consideration here only if one has the conceptual resources to attach significance to the fact that an artwork has qualities that its identical material counterpart lacks. Danto’s sensitive barbarians are not able to be aesthetically disappointed in this way precisely because they lack the rich conceptual framework which allows us to appreciate the meaning of works of art. And, try as we might, we could not construct a trick involving an art doppelganger from the world of mere objects that would disappoint them.

Henry Jenkins:

“My approach, however, contrasts sharply with writers like Noam Chomsky or Robert McChesney who understand popular culture primarily as a distraction from political participation. I see our relationships to popular culture as shaping our political identities in profound ways and am interested in the ways that people mobilize the contents of popular culture to understand the stakes in political struggles. Popular culture often expresses ideas or perspectives that are outside the consensus framed by the news media and are allowed to be expressed here precisely because popular culture is not taken seriously. Many subcultural communities draw on those resources to inspire their own acts of political resistance or to shape their own understanding of citizenship.

This approach represents a movement away from a traditional notion of public sector politics and towards an engagement with the more domesticated conceptions of citizenship that emerged through feminism, queer activism, and other identity politics movements. I believe firmly that one reason why fewer and fewer people are voting is that the realm of governance and elections has remained too abstract and removed from the realm of their everyday lives. Increasingly, we are getting our knowledge about the world around us from nontraditional sources and we are expressing our political concerns outside the realm of government.”

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS