There’s an epidemic

Stirring passions in young hearts

Even the old campaigners

Have got it really bad

Well we ain’t seen nothing like it

Since coronation day

But when the street parties sound

I’m going underground

To keep the rabid hounds at bay

Oh my my this war dance

A patriotic romance

No we ain’t seen nothing like it

Since coronation day

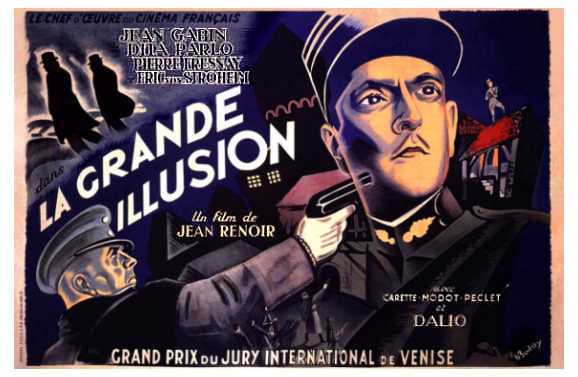

World War I seemed to do a rather comprehensive job of finishing off the idea that dying for one’s country was an aristocratic duty; and it also finished off, and put to rest literally, the aristocrats who were deluded enough to think so. On this theme, Jean Renoir and a masterfully chosen cast made their classic film, “La Grand Illusion”….

"Francois Truffaut and Orson Welles described Renoir as "the greatest filmmaker in the world". There is no doubt that Renoir has dominated both the French cinema of the classical period and the international pantheon of great auteurs. La Règle Du Jeu (1939) The second son of Impressionist painter Auguste Renoir, Jean grew up in the artistic milieu of turn-of-the-century Paris. Much - too much - has been made of this legacy, though it was of consequence for Renoir's realist aesthetics and financial independence."

Some of the earliest record of war and its consequences: the history of the fall of Troy, Gideon’s Army in Canaan and those pesky and frisky Philistines and Hittites – paints a bleak picture of what lies ahead for the United States.

President Barack Obama’s announcement of the end of combat operations in Iraq, a political Phd dissertation in how to speak without saying anything, doublespeak, was a drab, banal monument to wishful thinking: “Through this remarkable chapter in the history of the United States and Iraq, we have met our responsibility. Now it’s time to turn the page.” A war begun in lies,sold with a combination of moral or immoral suasion and blackmail, prosecuted with incompetence and brutality, has been concluded out of sheer exhaustion and combat ready burnout. As a shovel ready stimulus project, the grave digging has run its macabre course. For Americans, as for the Greeks before them, the story of the war and its consequences is just beginning with the end of the conflict….

"Of all the wars, the first world war seems the most emblematic, and the one which probably lends itself best to cinematic treatment. As no other war seemed as futile, it was easier to make convincing anti-war statements. Yet, paradoxically, great films on the subject have been few and far between since Jean Renoir's La Grande Illusion (1937), a paradigm for all subsequent films on the subject. Only Stanley Kubrick's Paths of Glory (1957) can be mentioned in the same breath as the films of the 1920s and 1930s."

But when the tickatape flies

And blood is on the rise

You know it’s got you in its sway

You got yourself a war dance

There’s a cheap sensation

Keeping Fleet Street wide awake

Everyone wants a slice of

The jingoistic cake

And they’re resurrecting Churchill

And bringing national service back

Fueling power and glory fever

Makes for a sicker Union Jack

Since 1938, when it was first shown in the United States, Jean Renoir’s famous film has been mistitled. It is called “Grand Illusion” , and as every high school student knows, this means “The Big Illusion” . The point is not without importance, because the proper title avoids an opening note of half romantic, lofty regret. There is scarcely a list of great films, long or short, that does not mention this one. It exemplifies an ancient truth: good art survives because as we change, it can change with us.

"Besides La Grande Illusion (1937), other great works during this period include Le Crime de Monsieur Lange (The Crime of Monsieur Lange, 1936), La Bête Humaine (The Human Beast, 1938), and La Règle du Jeu, (The Rules of the Game, 1939). These films tend to feature multi-participant narratives that not only allow the viewer to sympathize with the individual characters but also see the larger scheme of things and the social issues that concern them. This vision, this view of humanity at large, is what elevates Renoir’s films to the level of great artistic statements. To reach high levels of artistry, Renoir was always looking to extend his technical mastery of film and employ new techniques."

In the winter of 1936-37, when “La Grande Illusion” was made, in the world of the Spanish Civil War, of Mussolini and Hitler gulping down the West, of japan ravaging China, the film was a warning of the futility of war in the face of growing wars, an anatomy of the upheaval of 1914-1918 to show contemporaries how grim machineries had been set in motion. Today its pacifist intent, as such, seems somewhat less salient because so many more human beings know how futile war is and know, too, that no film can abolish it; in fact it may even enhance war by ingratiating it within the culture.

Yes I’m talking about this war dance

A patriotic romance

And I know all you poets

Have seen it all before

About the stirring of those young hearts

Oh my my this war dance… ( XTC, Colin Moulding )

" In the final act, Marechal and Rosenthal set out on the road seeking to escape Germany. Rosenthal has a badly injured foot, though, and they have no choice but to seek shelter in a rural farmhouse that is tended by a widowed German lady, Elsa, who is looking after her young daughter. Elsa’s husband and all her brothers had already died in the war, but she sympathizes with the human plight of the two French escapees and takes them in. "

Today the film seems a hard perception of inevitabilities, not glibly cynical but in the largest classical sense, pessimistic: a film that no longer asks for action but that accompanies us, noting our best, prepared for our worst. Since this state of mind, this undepressed pessimism, is now widespread, this film continues to speak, out of the change it incorporates, to a changing humanity.

Yet, in a wonderful and important way, “La grande Illusion” is a period piece, and Renoir was the ideal maker for it. The history of film is full of remarkable confluences. D.W. Griffith came along just when the newborn medium needed a genius to formulate its language. Eisenstein and Pudovkin came along in the Soviet Union just when the new society needed new artists to celbrate it in this new form. Six hundred years of Renaissance humanism, predictably ripening to decline, found a film elegist in a Frenchman born and nourished in its center, the son of a painter who had given “la belle époque” some of its humane and sensual loveliness.

"Marcel Dalio, who plays the key role of a Jewish soldier in this film, Lieutenant Rosenthal, also played a major role in La Règle du Jeu. The Jewish Dalio’s real, original name was Israel Moshe Blauschild, and both his parents died in Nazi concentration camps. He, himself, just managed to escape the invading Nazis in 1940."

Jean Renoir, son of Pierre Auguste, was born in 1894 in Paris. He wrote a biography called “Renoir, My Father”, which inevitably is almost an autobiography about himself. In 1913, the young Renoir enlisted in the cavalry, and in 1915 he was wounded in the leg, resulting in a life-long limp. In 1916, after his recovery, he became a pilot in a reconnaissance squadron. Marechal, a leading character in “La Grande Illusion” , is a reconnaissance pilot who is wounded. When the war ended, Renoir worked in ceramics for about five years, then in 1923 he began to write and direct films.

By the mid-1930’s he was one of the eminent directors of France, having made such highly regarded films as “Boudu Saved from Drowning” , “The Crime of Monsieur Lange”, and an adaptation of Gorki’s “The Lower Depths” , and was well launched on a career that, whatever one’s opinion of individual works, has as a whole had a significant influence on the later film world.

" Two World War I French prisoners have escaped from the Germans and have just made it to neutral Switzerland. A German patrol has been following their tracks in the snow and a soldier wants to shoot them, but his commander informs him that the two have crossed the border and are now safe. The viewer can see no border, however. The snow stretches in an undifferentiated plane. Humans make boundaries and then engage in horrendous bloodlettings to maintain them. Nature, like the frozen groundswell that doesn’t like Frost’s wall, is impervious to boundaries. This is not the only boundary in Renoir’s film. Deeper than national boundaries is the boundary between the elite officer class and the new Europe that is emerging. Erich Von Stroheim, playing the role of his life as Captain von Rauffenstein, is the rigid German officer who will fraternize with the French commander Bouldieu but not with the working class Marechal or the Jewish banker Rosenthal. He is fatalistic over the fact that old-time chivalry is dead and that others represent the future: Capt. Boeldieu: I think we can do nothing to stop the march of time. Capt. von Rauffenstein: Believe me, I don’t know who is going to win this war in the end. But it will be the end of the Rauffensteins and the Boeldieus."

…The ” Orestria” a trilogy of tragedies by Athenian playwright Aeschylus, portrays, in searing almost perverse detail, the aftermath of the Greek war. Agamemnon returns home to Argos, after defeating the Trojans, to be savagely killed by his wife, Clytemnestra, who cannot forgive her husband for killing their daughter, Iphigenia, at the beginning of the war. Agamemnon’s death provokes his son and daughter, Orestes and Electra, to kill their mother Clytemnestra. The Furies then pursue and torture Orestes until a trial by the gods in the final play of the trilogy.

The violence of the war with Troy doesn’t end with the “end of combat operations” – if anything, the spectre of war in domestic life is more savage than the cost of war on the battlefield. The violence of combat is at least simpler and more straightforward than the domestic battlefield. Homer’s “The Iliad” is a poem of pure savagery, almost Darwininan, but everything is out in the open. Men kill men and then rape, pillage and enslave women. The weak, unlucky or lousy fighters are reduced to corpses. The strong and fortunate revel. The cleanliness of the epic slaughter, the purity of arms, is transmuted, after the return home, into a tragic cycle of revenge and family murder. Might degenerates, or spirals bowlegged and tumbling head over heels to a dismal neurosis….

"Although Boeldieu has made way for the new France, however, divisions haven’t vanished entirely. Marechal and Rosenthal may huddle together for warmth at one point, but at another they argue and Marechal calls Rosenthal a “dirty Jew.” This is Renoir’s acknowledgement of French working class anti-semitism. But they come back together and, by the end of the movie, make it to Switzerland. "

“The camera’s point of view is not personally involved and subjective, but is seen from the perspective of a sympathetic, but somewhat detached, “silent witness”. This is achieved by Renoir’s preference for medium and long shots involving multiple characters, often in movement. The resulting point of view is thus more global and all-encompassing. His approach contrasts with the existentialist mise-en-scène of his contemporary and rival, Marcel Carné, who was the champion of “poetic realism”. Carné’s work was atmospheric, emotional, and often fatalistic concerning the romantic longings of his individual protagonists, while Renoir’s work was more reflective about the larger scheme of the human enterprise.

The work of both Carné and Renoir induce in the viewer a feeling of melancholy. Carné’s melancholy concerns the eternal loneliness of the individual and the hopelessness of romantic fulfilment. Renoir’s melancholy is less personal and more reflective on universal truths affecting humanity. Here in La Grande Illusion, there is an implicit faith underlying the film that ultimately the universal commonality of humanity will overcome the depredations of nationalism, racism, and outmoded social class distinctions. Yet Renoir’s view is not completely optimistic.”

Cast: Erich von Stroheim ( von Rauffenstein ); Jean Gabin ( Maréchal ); Pierre Fresnay ( de Bœildieu ); Marcel Dalio ( Rosenthal ); Julien Carette ( Actor ); Gaston Modot ( Engineer ); Jean Daste ( Teacher ); Georges Peclet ( French soldier ); Jacques Becker ( English officer ); Sylvain Itkine ( Demolder ); Dita Parlo ( Elsa ); Werner Florian; Michel Salina; Carl Koch. Awards: Venice Film Festival, Best Artistic Ensemble, 1937; New York Film Critics' Award, Best Foreign Film, 1938.

It would have been impossible for the man who made those early films to be unconcerned with what he saw happening in Europe and Asia and Africa in the mid 1930’s. Renoir prepared to make “La Grande Illusion” , based on a story that he says “is absolutely true and was told to me by some of my comrades in the war.” This combination of authenticity and of response to a sense of historical twilight; roots the film firmly in its period, using the best of an age to bid that age farewell.

To collaborate on the script with him, Renoir engaged Charles Spaak, one of those important film figures of whom the public knows little, like Carl Mayer in the German 1920’s and Cesare Zavattini in the Italian 1950’s: screenwriters who contributed greatly to celebrated eras. Spaak, the brother of Paul Henri Spaak, the former Belgian prime minister, wrote a number of memorable screenplays in a long career. By this time he had already written “La Kermesse Heroique” or Carnival in Flanders, for Jacques Feyder and the Gorki adaptation for Renoir.

" Fresnay is superbly dry as the aloof but good-hearted Boeldieu who determines to die gloriously rather than die with his class. But best of all is Von Stroheim, the prototype stick-necked Prussian even before the accident, but who is the most humanistic of all. For them and for Renoir this is a film to cherish again and again, a film which shows you how the smallest symbolic gesture may be worth a fortune, be it Boeldieu’s white gloves, Von Rauffenstein’s geranium or Marechal’s learning about Lotte’s blaue augen. In the end, all we can do is drink to Von Stroheim’s toast, “may the earth lie gently on our gallant enemy.” The age of such gentlemanly warfare is long gone."

“La Grande Illusion was first shown in Paris in June 1937, the month that Léon Blum’s government fell. Despite its ambiguities, the film was welcomed by the left who saw the sacrifice of the monocled aristocrat Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) to save the worker Marechal (Jean Gabin), as a symbol of the moribundity of the ruling classes. At his death, Boeldieu says to his captor and fellow nobleman Von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim): “For a common man it’s terrible to die in war. For you and me, it’s a good solution.”

But there is another possible reading. Boeldieu sacrifices his life because he puts loyalty to his French comrades, though they be a Marechal or a Rosenthal (Marcel Dalio), before loyalty to class. In the final scene, when the two POW escapees cross into Switzerland, the landscape on both sides is covered in snow, prompting Dalio to say “Frontiers are made by men. Nature doesn’t give a damn”. (Ronald Bergan )

It’s very difficult to pinpoint precisely what makes Renoir’s masterpiece so truly awe-inspiring, though its a mixture of transcendental poetry and the imperceptibility of the intangible. Through a combination of authenticity of vision, a perfect script, suitably war-torn settings and a host of fine performances, he conjures up an image of what might be called the last hurrah of the lost generation.

Opposing career officers Von Rauffenstein and Boeldieu, aristocratic enough to speak three languages fluently, meet to discuss the dimming of their society by the war. The German carries on, spinal injuries and metal skull plates and all, to “give the illusion of serving my country.” Is this illusion of patriotism the ‘grand illusion’ of the title, or is it rather the illusion of class divide? Men may be from different classes and nationalities, but they remain men, whether they sing ‘Watch on the Rhine’, ‘La Marseillaise’ or ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’, as they do at one point or another.

Even race and religion do not matter, with Rosenthal the Jew the most generous of the bunch in his feeding of the entire group from his deluxe hampers of chicken, pâte de fois gras, Périgord truffles, etc.. The atmosphere of war removes class to the point where it no longer matters. When one of the prisoners observes “man truly is an adaptable animal“, he’s speaking truer than he realises.

…But its never really over. Never to the point of point, despite the brainwashing,and the pablum, that “this time is different”. The lesson of Agamemnon in the Greek play of Aeschylus, if indeed there is a lesson in the middle of all this gore, is that war doesn’t end when we say it ends. He capably slayed the Trojan but also brought down the walls of his domestic life, destroying himself in this awkward exercise of incoherence. The war ends when the Furies we have unleashed become restrained; and that means not resolved or reconciled, just merely contained.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS