Adoption Agency Worker: Mr. and Mrs. Rubble, this is your little boy.

[Presents Bamm-Bamm]

Betty Rubble: Oh Barney isn’t he precious?

Fred Flintstone: Precious? They’d have been better off with the monkey.

Wilma Flintstone: Fred!

Betty Rubble: Does he have a name?

Adoption Agency Worker: Bamm-Bamm.

Barney Rubble: Is that short for something?

Adoption Agency Worker: Yes, Bamm-Bamm-Bamm. You’re going to have to take it slowly with this one, he doesn’t speak yet and is a little skimish around humans, but then again I would be too if I’d been raised by wild Mastadons. Ha ha ha.

Barney Rubble, Betty Rubble: Mastadons?

Adoption Agency Worker: Let’s not nitpick! A mammal’s a mammal.

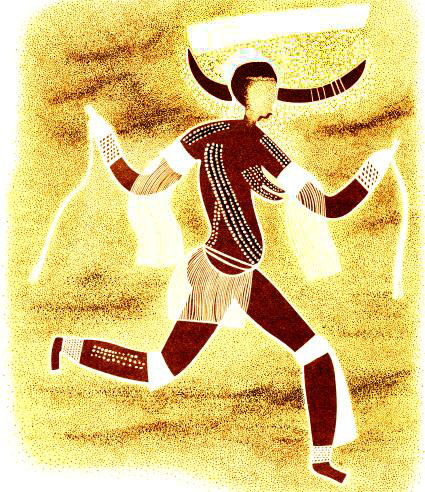

"The Tassili N'Ajjer rock carvings and wall paintings in modern Algeria show a picture of a world in the Sahara that we would not recognize. Instead of vast gravel plains and lakes of sand, there are highly realistic scenes of people harvesting the fruit of date-palm trees, a village with a herd of cattle, people defending their flock of sheep from a lion attack, and scenes of religious ceremony. Some of the earliest carvings are at least 8000 years old. "

“We are locked in history and they were not,” Herzog says about the cave artists in his voice-over to the film, a comment he admits needs some explanation. “We have a sense of history and we act according to history, so our actions are … guided and steered by us living in history,” he says. “However, Paleolithic people … for them time had a different meaning and dimension than for us.” “And yet they are not completely remote from us because … we sense that this was like an almost abrupt event — the awakening of the human soul, the modern human soul.” ( Werner Herzog, on “Cave of Forgotten Dream” )

"Cave of Forgotten Dreams set photos are quite impressive because they give first look into the latest directorial of an Oscar nominee filmmaker. Upcoming history and documentary drama seems to have captured exclusive and magnificent sceneries in it because Cave of Forgotten Dreams images showcases the mind blowing and interesting looking images that bring out the oldest known pictorial creations of humankind in their astonishing natural setting."

Talking to the caveman about poetry.We are back to our wild roots on a Bedrock holiday. The New Yorker’s Judith Thurman wrote an 8,000-word article on Chauvet caves in France, yet was unable to talk her way inside for a first-hand look.Werner Herzog not only managed that, he brought along 3-D cameras, lights and a small crew. How did he do it? “When things are coming to the essentials, I can speak in angels’ tongues.”

Its the very depths of human history.Its called “Cave of Forgotten Dreams”. Werner Herzog has entered another dimension in the Chauvet caves. The film is gorgeous, but given the parameters of the subject matter; a bit plodding and frankly boring. But thats totally beside the point. Herzog goes to places the rest of us cannot, dare not, and sometimes even should not, but we’ll go anyway.

Michael Hogan:Herzog speaks to scientists in the area about everything from the spirituality of paleolithic societies to the musical instruments and weaponry they employed. After one moustachioed Frenchman gamely attempts to chuck a spear to show how the old-timers did it, Herzog forces him to acknowledge that the paleolithic men would have done a far better job. This seems a bit rude, until you understand what Herzog is getting at.

It is generally assumed that prehistoric art was inspired by magical practices; in short that it was born of religion. its existence in france and Spain , in deep dark caves resembling true sanctuaries, only strengthens the theory. There is no doubt that the sorcerer in the Trois Freres cave in France and the decapitated bear in the cave at Montespan can only have had a magical character. Art for art’s sake, according to this theory, did not exist and must have been an invention of men who had reached a high stage of evolution. Yet this rule must have been subject to exceptions, for certain painted or engraved subjects apparently have no mystical element and certainly seem to be the product of pure imagination. …

"The following phase in the Sahara, the Round Head paintings, shows little relationship to the animal engravings. In fact, the leader of the Tassili expedition, Henri Lhote, found the Round Head art so different from traditional forms of prehistoric art that "we felt we were moving about in a world that bore no relation to any other, a world apart." Many hundreds of these remarkable compositions have yet to be published, but already famous are the depictions of beings whimsically named "Martians" by Lhote."

Herzog’s film is such a time warp backwards into nature its a romanticist’s nightmare; completely severed from nature, disowned, unmanned. At the same time, something wonderful about the whole thing as well. Spear hunting and hacking away at meta-sized wild game seems pretty futile, even if a necessity. Maybe we could serve as a caddy for the spear bag. But does it really matter? We are adapting to the future even as we shed the qualities that helped us make it this far. The process is admittedly ugly, even downright repulsive. However, what’s the alternative?

"The volume is Henri Lhote's account of the discovery of prehistoric paintings in the central Sahara, some as old as eight thousand years. Not only did these discoveries demonstrate that this area had once been fertile, but they established the complexity and sophistication of the cultures that had inhabited the area, including, as

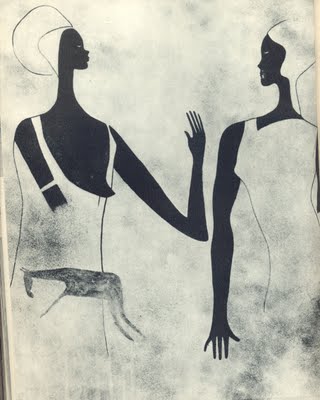

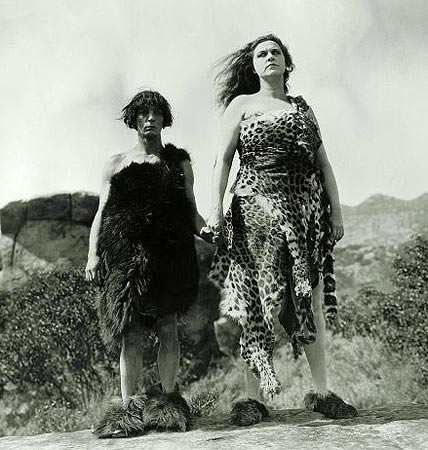

book's publisher puts it, "the earliest examples of Negro art we possess."Herzog’s film does seem somewhat based on the Henri Lhote expedition in 1958 where he discovered astonishing murals made by Stone Age herdsmen in a desolate area of Algeria that was once green, in the Tassili plateau, the home turf of the forbidding Tuareg tribe. The refinement of drawing and anatomical mastery of the Tassili painters are nowhere more splendidly expressed than in the work above. The profiles of the two girls, according to Lhote was not exactly “negroid” but suggested the women of the Peul tribe. Their arms and hands are treated in a manner resembling that of certain Egyptian paintings of the Eighteenth to Nineteenth dynasties and the dresses they wear look like those of the period, claimed Lhote.

"In Jabbaren, in the Tassili mountains, Algeria, south of the Hoggar. A 6m high character with a large round decorated head. The massive body, the strange dressing, the folds around the neck and on the chest suggest some ancient time astronaut"

The people of the Tassili had the decorative sense and evidently knew how to paint. But why did they paint? Probably representations of gods and sorcerers as well as just painting for sheer pleasure, or so it would appear given the fascinating forms full of balance and elegance as well as attitudes that reflect motion.

Summary: Raquel Welch’s Cleavage versus Prehistoric Monsters: Whichever way this bout goes, the viewer wins! (David): Okay, so I know that it’s hokey science from the get-go to throw cavemen in with dinosaurs. Technically, our closest point-of-view ancestors at this stage would be small rodents—with no cleavage to speak of—who scurried into holes when the thunderous feet of the thunder lizards came thundering. Unless, that is, you’re one of those creationists who think the dinosaurs were wiped out in The Flood. Then, God help you, you shouldn’t be watching a movie with this much cleavage anyway.

Herzog’s latest film, completed, by his own reckoning, just fifteen hours before its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival , is a 3-D cabinet of wonders that takes viewers deep inside the Chauvet caves, where the oldest known cave paintings — dating to 30,000 BC — were discovered in 1994. The cave now boasts a bank-vault door, and admittance is restricted to a tiny coterie of scientists, who can enter for just a few hours at a time, a few weeks of the year. This is both to protect the caves from contamination, and the researchers from the effects of carbon dioxide and radon poisoning.

Of course, that theory raises some questions about Noah’s selectivity. Was it all the animals, or did he get to pick? Sure, I can understand space constraints posed by brontosauruses (brontasauri?); the elephants were already pushing it. But, hey, there were dinosaurs the size of chickens. Maybe they did get on, and food shortages after forty days on the high seas sealed their fate—they may have tasted like chicken, too. (Nick): And, back to the movie… (David): Whether you buy any of that or not, the whole kooky idea of man and dinosaur cohabitating is a great scenario for thrills! Look at all the scientific hoops Crichton and Spielberg jumped through so we could plausibly entertain the idea while enjoying what we really paid our money to see: lawyers getting bit in half by tyrannosauruses (tyrannosauri?)

Herzog’s decision to film in three dimensions was not influenced by the recent glut of 3-D movies. “It was imperative to shoot it in 3-D,” he says, “because we are probably the only ones ever being allowed to film in the cave. And painters 32,000 years ago utilized the drama of the niches and bulges and pendants of the rock. There’s never a flat surface. They understood a protrusion, a bulge which is now the neck of a bison that charges; a horse comes out from a niche and looks at you. So it’s obvious that they understood the spatial quality of what they were doing.”

"Being prehistoric times (or is it?) the characters don’t have names. Vaughn is “The Symbol Makers Teenage Son”. His dad, not surprisingly, is “The Symbol Maker”. They are members of a prehistoric tribe governed by ancient rules that basically prevents them going “beyond the river”, as the first clip will explain. Despite food being scarce on their side of the water and plentiful on the other, they must not cross for fear of encountering “The god that brings death with its touch”, that’s another thing I adore about this film. It’s like Corman wanted every character to have a name that takes a fortnight to say."

The film lingers on the charcoal portraits of animals, some of them more than seven times as old as Egypt’s great pyramids, yet as clear as if the artist had just stepped away. Paleolithic Picassos ? “It’s a beautiful speculation, sure; what would they do if they saw us?” he says. “I try to speculate sometimes that in some niche … if we dug through it we might find a band of them still hiding, and going out at night and hunting, and all of a sudden encountering us, like aliens landing on our planet. The film grapples with such notions as the roots of culture, artistic expression and music. Herzog interviews scientists outside the caves, one of whom shows off a reconstructed prehistoric flute.

When Women Had Tails. Lina Wertmuller:To differentiate then each of the cavemen has a particular trait: Wolff's werewolf-looking figure combines a more inquisitive nature with a bad temper; another has a propensity to lose parts of his anatomy in accidents, but for a time regrow them, before spending the latter part of the film as just a head; while a third, complete with a Harpo Marx style hairdo, is coded as gay and soon falls in love with a more civilised, trickster-conman type caveman played in characteristic self-deprecating manner by Lando Buzzanca.

It’s tuned to the same pentatonic scale still used the world over, and can play The Star- Spangled Banner, as the scientist demonstrates. He points to an example from the film. Someone painted a partial portrait of a reindeer in charcoal on a cave wall, and someone else completed it. But radiocarbon dating shows that between one artist and the next, 5,000 years had passed. “I know I’m tied into history and they were not,” Herzog says. “It’s a fascinating idea, to live not within the strictures of history.”

When Women Had Tails."This prehistoric comedy might perhaps be glossed as a live action version of The Flinstones done in the style of the commedia all'italiana meets The Marx Brothers and The Three Stooges, with an effective mixture of physical and visual humour, which comes across regardless of the language one is watching it in, and wordplay, which obviously requires a knowledge of Italian - at least in the version under discussion here. The always-welcome Senta Berger plays Filli, a thoroughly modern looking cavewoman dressed in figure-accenting furs."

Cave of Forgotten Dreams takes a bizarre turn in its final moments, when Herzog leaves Chauvet to visit a nearby nuclear power plant, where the water from the cooling towers has been used to create a tropical breeding area for crocodiles. “Radioactive albino crocodiles” he calls them “That’s the beauty of storytelling; that’s the beauty of cinema … I give you the wildest stuff you can get, and audiences love it as much as I love it. “I just heard about a crocodile farm and I said I want to see it and maybe we should film something. And then I walk in and I see these two albino crocodiles and my heart stopped for a moment and I said: ‘We stop everything, we must film this.’ ”

“What will these albino crocodiles see when they see the paintings? What will they make of it? Today, we are the albino crocodiles, looking at the painting. We can only be awestruck, but we can never understand why they were painted, by whom they were painted, and so they mystery will linger.” He continues: “The film is over, clear, but then comes postscript. [And] as it is separated as postscript, you can go as wild as it gets. Ultimately one day they will take me out in a straitjacket for obsessive wildness.”

Caveman, Carl Gottlieb, 1981: Ringo Starr met his future wife Barbara Bach whilst filming this spoof of the genre

Barney Rubble: You’re afraid to tell Wilma, aren’t you?

Fred Flintstone: [skids the car to an abrupt halt] Afraid? Now let’s get this straight, Rubble, I don’t need permission from my wife to make a decision. In my cave, I reign supreme, *SUPREME*.

Barney Rubble: I won’t tell her, Fred.

Fred Flintstone: [relieved] Thanks pal

Michael Hogan:"I was especially interested in the white crocodiles that show up in the epilogue, which serve as Herzog’s metaphor for the simultaneously advanced and degraded condition of 2010 vintage humankind. According to Herzog’s narration, the crocodiles are the mutant offspring of animals that have been living in a French greenhouse heated by the runoff from a nearby nuclear power plant. Later in the day, I got a phone call from a fellow named Ken Berard, who works at the Nuclear Energy Institute, in Washington, D.C.. He sent me some links which suggested that the reptiles in question are in fact albino alligators whose whiteness has nothing whatsoever to do with radiation. I then asked a colleague who speaks French to phone La Ferme aux Crocodiles, where a spokeswoman confirmed as much and added that the alligators had been shipped, alive, to France from Louisiana earlier this year."

a

a

a

a

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Dave, the paleolithic painting has been proven for the Sahara. It was once a lush forest but vanished after a few thousand years. There is deep below the Sahara a massive aquifer trapped by the sands.

Yes i know. I didn’t have the space or too much context room to get into it.