Its the Utopians versus the Dystopians, and at this juncture the latter have prevailed. Communities with European roots embraced the equalizing demands and freedoms of the New World’s open frontier, even as the new country claimed the pursuit of happiness as an inalienable right. Though their inspirations varied—theocracy, millenialism, socialism, theosophism, behaviorism—they all reflected the American dream of a better world, now.

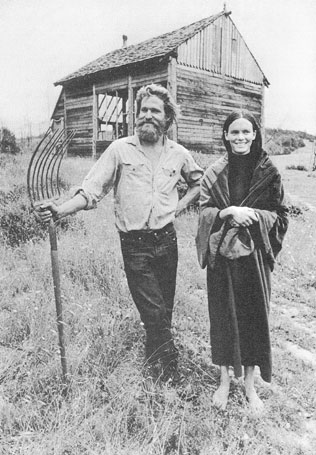

Sara Davidson:Getting close to the earth meant conditioning their bodies to cold, discomfort, and strenuous exercise. At Wheeler's, people walk twenty miles a day, carrying water and wood, gardening, and visiting each other. Only four-wheel-drive vehicles can cross the ranch, and ultimately Bill wants all cars banned. "We would rather live without machines. And the fact that we have no good roads protects us from tourists. People are car-bound, even police. They would never come in here without their vehicles." Although it rains a good part of the year, most of the huts do not have stoves and are not waterproof. "Houses shouldn't be designed to keep out the weather," Bill says. "We want to get in touch with it." He installed six chemical toilets on the ranch to comply with county sanitation requirements, but, he says, "I wouldn't go in one of those toilets if you paid me. It's very important for us to be able to use the ground, because we are completing a cycle, returning to Mother Earth what she's given us."

From Thomas More’s famous Sixteenth Century work that introduced the word “Utopia” through Thoreau’s Walden to Neal Stephenson’s 1992 Snow Crash, writers of novels, essays, and political tracts addressed an imagined future in which human beings designed new ways to live in community. Illustrating the opposite view are a handful of dystopian novels such as Ray Bradbury’s Farenheit 451, the 1953 portrayal of a world where the written word is forbidden. …

“Let us be lovers we’ll marry our fortunes together.”

“I’ve got some real estate here in my bag.”

So we bought a pack of cigarettes and Mrs. Wagner pies

And we walked off to look for America.

“Kathy,” I said as we boarded a Greyhound in Pittsburgh

“Michigan seems like a dream to me now

It took me four days to hitchhike from Saginaw

I’ve come to look for America.”

Laughing on the bus;

Playing games with the faces;

She said the man in the gabardine suit was a spy;

I said “Be careful his bowtie is really a camera.”

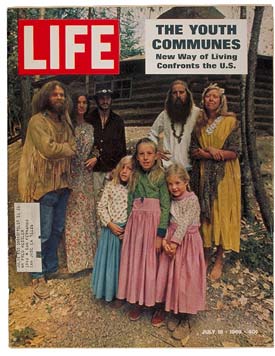

Still from Bruce Geisler documentary "Free Spirits" on the Renaissance Community. "The documentary “Free Spirits” functions an amazing window to a lost world, infiltrating the lives and minds of participants in an actual hippie commune, created in the Berkshires in Western Massachusetts the late 1960s by Mike Metelica, prone to childhood visions and an interest in being a rock and roll bad boy. The commune — originally known as the Brotherhood of the Spirit and later as the Renaissance Community — began as a treehouse in Leyton, Massachusetts, that attracted other kids to hang out — it blossomed into a naïve but fully-formed alternative society of young adults that imagined itself poised to transform the world into a new era of beautiful socialization and peace. The story, however, is not that simple — this meticulously gathered oral history reveals the ups and downs of the community, the challenges of the many to function as one, the trials of Metelica to live up to his initial reputation as a spiritual leader. At its peak, the community had around 400 residents, all fulfilling various functions and rising to the occasions that needs demanded — if they need a building, members learned how to construct one; if they need bathroom facilities, members taught themselves plumbing. They also had plenty of time for artistic and spiritual exploration — and sexual as well — but no society can remain stagnant and the community was no exception. Their extended vacation from the harsh realities of modern America was to send them on a nosedive involving finances and drugs and rock and roll and a cult of personality that divides the community and, eventually, causes it to dissipate into the smallest pockets."

Our forefathers, like ourselves, were always in hot pursuit of the good life. They built their own communes, only to learn that transcendental ideals and prayer and even group sex do not suffice to weld a community together. Looking back on his sojourn at Brook Farm, the famous but short lived transcendentalist community near Boston, Nathaniel Hawthorne felt nostalgia. “More and more,” he said, “I feel we struck upon what ought to be a truth. Posterity may did it up and profit by it.”

Posterity has been digging for whatever truth was buried at Brook Farm and at the scores of other intentionally different communities , set apart from the ordinary culture, that our ancestors hopefully began. One general truth is easily apparent: the democratic society established by the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution was the most open in history, the most hospitable to social innovation running against or across the common grain. What profit, in the present climate of energetic social experiment, can be derived from a look at a few of the more notable efforts of the past?

The Perfect Human: I want to spend time with you, I want you to plan activities for us, that reveal your inner most thoughts, dreams and desires. Human connections are slipping through the cracks one day at a time, wether it automated telemarketers or "self" check-out machines we are slowly losing the "human being". I want you to be a part of my Top 8...15...25....100, I need to experience the rush of the web friend conquest, and I need to document it!! I want to get to know you better, and I want you to know me! So If this is at all interesting to you, and you are willing to participate in this experiment with me, please contact me!! LET'S HANG OUT!!! Leave me a comment, or send me an e-mail: Whopgenius4hire@gmail.com

“Toss me a cigarette, I think there’s one in my raincoat.”

“We smoked the last one an hour ago.”

So I looked at the scenery, she read her magazine

And the moon rose over an open field.

“Kathy, I’m lost,” I said, though I knew she was sleeping.

“I’m empty and aching and I don’t know why.”

Counting the cars on the New Jersey Turnpike:

They’ve all come to look for America

All come to look for America ( Paul Simon, America )

The Perfect Human Being:This is my "real life" friend request, my search for an available friend network. I want to experience the "real thing" I want to make real life requests, to replace photo comments with face to face compliments. Instead of reading about you, I want to hear it from your lips. I want you to teach me everything that you know, so that I can know it too. This is meant to encourage your sense of community spirit, and your belief in me as an active member, an essential personality. It's time to "RALLY" WE COULD BE BFF IN NO TIME!!!

One thing that quickly attracts notice is that most of the earlier communal experiments were of pitifully short duration, in inverse relationship to the ardor with which they were launched. It is an astonishing fact that the hands-down winner, as far as longevity goes, is a society of dedicated celibates. The Shakers were established in America almost simultaneously with the Declaration of Independence; they throve mightily through the middle of the nineteenth century, and endured into the twentieth. There are very few Shakers left today, total celibacy not that appealing, but thy are still with us.

Like most communal groups, the Shakers began as a dissenting religious sect. Officially called the United Society of believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, they had an unusual view of that great event; Christ had already appeared a second time, not as a man, but as a woman. Her earthly name was Ann Lee who had been born and brought up in the dismal slums of Manchester, England in the 1730,s. She married young and hated it; her aversion was reinforced by a vision in which the Lord, she said, revealed to her the exact identity of Adam and Eve’s sin, naturally sexual intercourse, and furthermore explained that God was bisexual and that she, Ann, was the female incarnation as jesus had been the male.

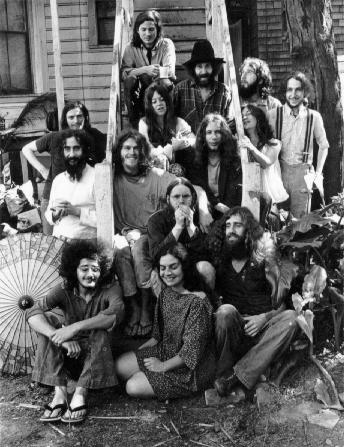

"Back in San Francisco, the original Diggers had dropped that name soon after their Death of Hippie parade/event/ritual. Then began the Free City cycle of activities before their final exit from the stage that the City streets had provided for the past two years. But by then a new Free community had sprung from the Digger legacy. Where the Mime Troupe had taken their art from the confined space of theaters into the parks, and where the Diggers had taken their energy from the parks into the streets, now there was a reversal of this trend. Free went indoors, back into the new spaces that were being created in the old Victorian homes and renovated warehouses of San Francisco. The glaring onslaught of media attention drove the movement underground again. The Scott Street Commune gathered in the backyard of the Redevelopment-owned Victorian which they occupied from 1971 to 1974. The Free Print Shop was in the basement of the house next door. The Free Bakery would be located on the second floor next door after the Commune took possession of both buildings. This photograph was taken by Miriam, ca. mid-1972. Several members are absent."

A small but growing number of disciples believed her, and in 1774, as Mother Ann, she led them to America. Since they were given, in their devotions, to a great deal of writhing, quivering, and general jumping about, they were known to outsiders as Shakers; they didn’t seem to mind. Ann died in 1784, but her truth went marching on. they were communistic and despite Gods revealed bisexuality, they were elaborately celibate; and this austerity projected itself onto their whole lifestyle.

For amusement, somewhat surprisingly, the Shakers went in for dancing. Musical instruments were frowned upon, but the Shakers became adept at rhythmical singing and chanting that would accompany their highly ritualized no body contact movements that avoided the conventionalized flirting of square dancing, reels or minuets. It was easy to parody the Shakers, as Dickens did, yet on the whole Mother Ann’s heaven on earth earned the respect and even admiration of nineteenth century intellectuals who were impressed the the Shaker’s pacifism, relatively equal treatment of women, opposition to slavery, industry, orderliness ,cleanliness, and integrity.

"Clarke and her longtime collaborators, playwright Alfred Uhry and music director Arthur Solari, have created a 70-minute piece that explores the effects of the Shakers' strict community and, by extension, any oppressive society. In the beginning, six women in white bonnets and simple full dresses sit opposite a group of five men in hats and black suits, gathered for worship. Their good-natured laughter soon is replaced with spontaneous hymn singing, rhythmic stamping and clapping, and ritualized dancing in lines and patterns, the sexes always apart. These activities are interrupted from time to time by sudden testimonials glorifying the Shaker life. There's also impromptu speaking in tongues, violent possession of the spirit, and improvised solo dances. "

“it isn’t that god is only fighting the devil. he’s also debating within himself or herself what the next proper course might be. I wish to suggest that it is in experiencing the play of this complexity that future theology could find its nourishment rather than in the churchly insistence that god’s final intentions are all in the book. no, I don’t see the laws of existence as etched in stone with no deviation permitted. no absolute heaven and no absolute hell” – norman mailer. ( from Hune-Martin Buber Institute )

The Shakers were of lowly origins; the Owenites started at the opposite end of the social and economic spectrum. Robert Owen was the owner of huge cotton mills in Scotland before he was thirty; rich but kindly, he introduced sensational reforms but his dream was of better things: A paradise where private property and greed would be abolished, three hour work days, and health, education and blissful happiness for all.

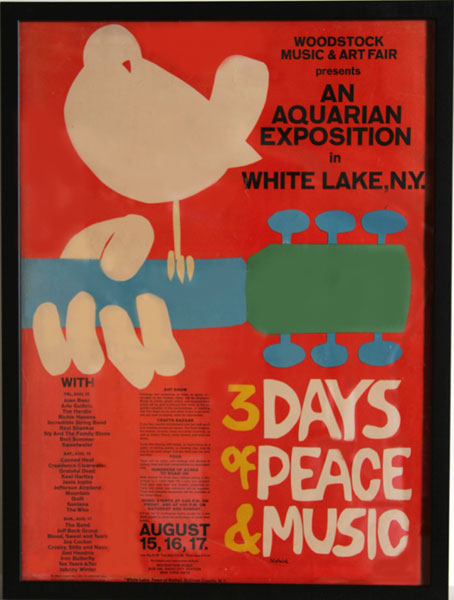

Arnold Skolnick Woodstock poster. Artie Kornfeld:"We had included the words "Music and Art Fair" because our intentions were always to make this more than just a concert, but a total showing of our generation. We wanted to include Arts & Crafts, Yoga and Spiritual directions ...and what was to us, the whole Woodstock Nation."

Owen purchased a communal village in Harmonie, Indiana that he purchased from George Rapp, leader of a group of German separatists: $135,000 in 1825 for twenty thousand acres of good land, large orchards, houses, mills, craft shops, community centers and a hospital. Renamed New Harmony, he saw this community as a “half way house” to a larger project. Nonetheless, about a thousand arrived by the end of 1825. Although a high percentage of them were people of refinement, capable of brilliant conversation, elegant entertainment, and dazzling theorizing, few had any notion or interest in how to plough a field, repair an outhouse or mix concrete. Owen sanguinely agreed to pay them $1.50 a week of of his own pocket, no matter what they did while he went off to Europe to try to interest more intellectuals in his project.

"Back in September Michael Dashkin, Brian Dennison, and I drove around the Midwest in lackadaisical pursuit of collapsed utopian communities. The highlight was an abandoned Michigan amusement park once run by a religious order called the House of David. The fairgrounds were as overgrown as the facial hair of its long ago proprietors."

He returned in 1826 with a brilliant collection of savants that was to be known as the “Boatload of Knowledge”. “It found favor,” wrote his son Robert Dale Owen, ” with that heterogeneous collection of radicals, enthusiastic devotees to principle, honest latitudinarians and lazy theorists, with a sprinkling of unprincipled sharpers thrown in.” Dissenters arose and they were given land a couple miles out of town,k and then there was objection to Owen’s teetotalism and the drinking crowd set up their housekeeping in another settlement. The experience wound down from there. Owen however, never abandoned the socialist struggle: he died not only with his boots on , at the age of eighty-seven in 1858, but in the middle of a lecture he was giving on “The Human race Governed Without Punishment.”

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Utopianism may only be tribal, as we seek that time and place we had lost. This might be pronounced with Europeans who came to the New World due to the dehumanization of Europe.

It seems to be the issue that Walter benjamin had latched onto and wanted to bring the discussion into the theological realm as you implied with that lovely quote. But the tribalism remains a sticky wicket…