According to the “knowability thesis,” every truth is knowable.Frederic Fitch’s paradox refutes the knowability thesis by showing that if we are not omniscient, then not only are some truths not known, but there are some truths that are not knowable. The paradox of knowability is a logical result suggesting that, necessarily, if all truths are knowable in principle then all truths are in fact known.That assumes that truth has some innate characteristic of logic, and underlying coherence, which, if enough effort is applied is likely to rise to a conscious level.

"Yes, it is necessary to live without this knowledge. I think of the play “Our Town”. Someone claims that only poets and saints really suck out the marrow of life. Perhaps Flannery O’Connor’s stories, such as ”A Good Man is Hard to Find”, suggest that the heinous, nihilistic sinners also sense the truth about life and death. Perhaps we are still so genetically engaged in the acts that promote living on a personal level, like the simplest of animals–survival–that we fail to think as do the philosophers, saints, poets, and great sinners. "

It is said that God moves in mysterious ways, and only he possesses the omniscience to be everywhere. But what if this was false? An untruth. By extension, if in fact there is an unknown truth, then there is a truth that couldn’t possibly be known. More specifically, if X is a truth that is never known then it is unknowable that X is a truth that is never known. The proof has been used to argue against versions of anti-realism committed to the thesis that all truths are knowable.

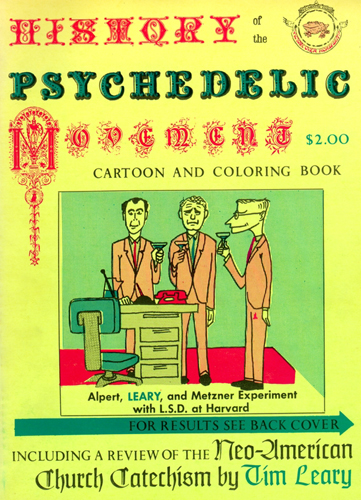

"When Harvard dismissed Leary in 1963, he set up the Castalia Institute in Millbrook, New York, to continue his studies. Leary's approach to taking LSD was the opposite of Ken Kesey'sÐLeary believed in "set and setting," a practice of taking the drug in a controlled environment, as a safeguard against bad trips. He coined the phrase "Turn On, Tune In, and Drop Out," and formed the "League of Spiritual Discovery," an LSD advocacy group. In the mid sixties, he began attending numerous musical events and public forums that promoted the use of LSD. Leary spent a number of years in prison for various charges related to drug possession."

For clearly there are unknown truths; individually and collectively we are non-omniscient. So, by the main result, it is false that all truths are knowable. The result has also been used to draw more general lessons about the limits of human knowledge. Still others have taken the proof to be fallacious, since it collapses an apparently moderate brand of anti-realism into an obviously implausible and naive idealism.

…The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.

If one believes Homer, Sisyphus was the wisest and most prudent of mortals. According to another tradition, however, he was disposed to practice the profession of highwayman. I see no contradiction in this. Opinions differ as to the reasons why he became the futile laborer of the underworld.

To begin with, he is accused of a certain levity in regard to the gods. He stole their secrets.You have already grasped that Sisyphus is the absurd hero. He is, as much through his passions as through his torture. His scorn of the gods, his hatred of death, and his passion for life won him that unspeakable penalty in which the whole being is exerted toward accomplishing nothing. This is the price that must be paid for the passions of this earth. Nothing is told us about Sisyphus in the underworld. Myths are made for the imagination to breathe life into them. ( Camus )

"Camus in "The Myth of Sisyphus," said basically that there's only one question, "Am I going to kill myself today?" once you get that one figured out the rest is - small potatoes. "

Events continually unfold, and its often recurrent and chronic pattern would indicate that the unknowable is somehow blocking a comprehension and that even this search for comprehension may be in vain. Like the myth of Sisyphus, this odd and sometimes perverse relationship with the deities by necessity leads us to the default position of Neitzsche’s eternal recurrence. Perhaps there is an imperative necessity to go deeper and change the settings that seem to regulate our collective existence.

"... his case for the benefits of psychedelic drug use, noting that millions of Americans have had hallucinogenic experiences: "We include marijuana smokers, the adepts in hatha yoga, meditators, peyote eaters, mushroom eaters, the LSD cult, and those millions who have had an involuntary psychedelic experience, those institutionalized mystics we call psychotics." Leary suggests historical, psychological, and biological bases for his arguments. The book also includes a number of poems from Lao Tse that Leary believes were a result

psychedelic experiences."

…At the very end of his long effort measured by skyless space and time without depth, the purpose is achieved. Then Sisyphus watches the stone rush down in a few moments toward that lower world whence he will have to push it up again toward the summit. He goes back down to the plain.

“It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me. A face that toils so close to stones is already stone itself! I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step toward the torment of which he will never know the end. That hour like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock.

If this myth is tragic, that is because its hero is conscious. Where would his torture be, indeed, if at every step the hope of succeeding upheld him? The workman of today works everyday in his life at the same tasks, and his fate is no less absurd. But it is tragic only at the rare moments when it becomes conscious. Sisyphus, proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious, knows the whole extent of his wretched condition: it is what he thinks of during his descent. The lucidity that was to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory. There is no fate that can not be surmounted by scorn.” ( Albert Camus )

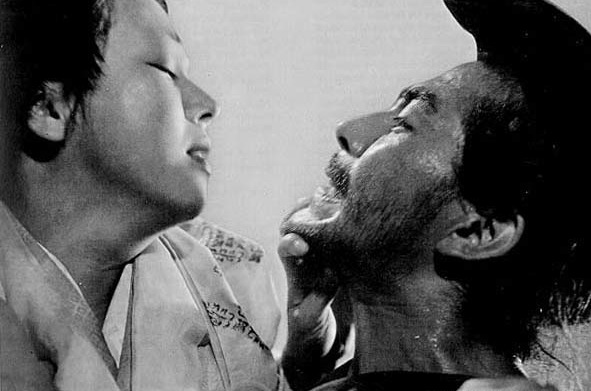

Akira Kurosawa’s vision, his power to make the screen teem with riches, produces a question: Can an artist really have bothered to make a film about the “knowability of truth”? The answer, well, it has to be ambiguous; one that would ask more than it could rationalize. And with regard to Japan, the inextricable link between Japan and the Atomic bomb is often a dramatic subtext for this ambiguity. The beauty of film, and also its flaw, is that we know where we are at every moment; we know the complexity of the narrative and as such, the “unknowability of truth” superficially, does appear as a trite theme. …

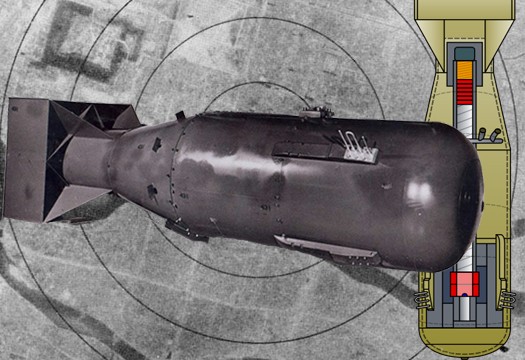

This past August, A U.S. representative participated for the first time in Japan’s annual commemoration of the American atomic bombing of Hiroshima, in a 65th anniversary event. The site of the world’s first A-bomb attack echoed with the choirs of schoolchildren and the solemn ringing of bells as Hiroshima marked its biggest memorial yet. At 8:15 a.m. – the time the bomb dropped, incinerating most of the city – a moment of silence was observed. The commemoration, began with an offering of water to the 140,000 who died in the first of two nuclear bombings that ensured Japan’s surrender in World War II. As for this and may other tragic events, the Why’s? are in the majority.

The very quality of Kurosawa’s art opens up this banal version of relativism to reveal the element that generates the relativism: the element of ego , of self. This curse, this weight, that is like the stone Sisyphus can’t seem to unload. Finally, “Rashomon” deals with the preservation of self, an idea, that in this film outlasts earthly life. That idea is not the sanctity of the individual as a political concept, not the value of each soul as a religious concept, but stark fundamental “AMOUR PROPRE”.

"So, point-of-view is not so much about who is telling the story, but how he sees the world. You don’t even have to limit the narrative to just the things a character thinks and sees, as long as the world you are showing is colored by his attitudes. The textbook example of using point-of-view is Kurosawa’s Rashomon. You see the same event three different times, from three different perspectives. The details and the feeling of the story are widely different with each telling, depending on the attitudes of who is telling the story at the time."

When Rashomon opened in New York in 1951, it was the first Japanese film to be shown there in fourteen years. The cultural shock that followed the Venice Festival showing was a smaller mirror image of the shock felt in Japan a century earlier when Commodore Perry dropped in. Then the Japanese had learned of a technological civilization about which they knew very little; now the West learned of a highly developed film art about which they knew even less. The first japanese director to be known in the West was Akira Kurosawa, who made “Rashomon” , and as it turned out this was fortunate, because Kurosawa was one of film’s great masters.

"The world's first nuclear bomb, lovingly named "Little Boy," was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. In one instant, it killed an estimated 140,000 people, effectively ended WWII, and ushered in a new era of military strategy based on apocalyptic-style destruction. The bomb used a simple "gun method" to achieve the nuclear fission chain reaction: It worked by using conventional explosives to blast two pieces of uranium-235 into each other inside the bomb chamber, which would then go critical and commence bringing about death and destruction in a very good impression of 18,000 tons of TNT."

The script of Rashomon, by Kurosawa and Shinobu Hashimoto is based on two short stories about medieval Japan; From the first story, “Rashomon” the film takes little more than a setting: the place where the film begins, to which it returns, and where it closes- along with a mood of desolation caused by the waste of civil war. Rashomon was the name of the largest gate in Kyoto, the ancient capital of Japan ; it was built in the eighth century, and by the twelfth century, the time of the film, it was already in disrepair.

In this great but dilapidated gate three men- a woodcutter, a priest, and a man called simply a commoner- huddle together out of a pouring rain and recount various versions of a murder that took place recently in the vicinity. The second story, “In a Grove” is the source of the murder narrative. There are some central facts: a samurai and his wife traveling through a forest were waylaid by a notorious bandit, who tied up the husband and ravished the wife; the husband was killed and his body was found by the woodcutter.

There are four versions of the events surrounding these central facts, and we see each of the versions as it is recounted, and each are wildly different. The bandit say he assaulted the wife who quickly became compliant. Afterward, at the wife’s insistence , he released the husband so that they could fight, and killed him in a long hazardous duel. The priest said that after the rape the bandit left. Her husband looked at her with such hatred, perhaps because she had not resisted sufficiently, and in a frenzy of grief and shame she apparently killed him, then ran away.

" If you've ever seen 'Dr. Strangelove,' you understand the combination of fear, military escalation, and sheer insanity that followed the development of the bomb. A single bomb dropped from a propeller-driven airplane gave way to thousands of thermonuclear warheads squirreled away around the globe in missile silos, jet bombers, and nuclear submarines during the greatest arms race of all time. By the end of the 1950s, the world had enough nuclear firepower to blow up half the solar system. Thankfully, cooler heads prevailed when Little Boy's cousin Fat Man blew up Nagasaki and became the last nuke ever used in battle."

The third version, also told by the priest, is that of the dead husband who speaks through a medium. The husband says that after the seduction his wife urged the bandit to murder him and take her along. The bandit declined, released the husband, and left. Alone, the husband killed himself with a dagger. Later, after his death, he felt someone take the dagger away.The woodcutter claims he came along just after the ravishing and watched from behind a bush. The wife was crying, and the bandit was pleading with her to go away with him. She said the men would have to decide whom she was to go with.

She cut her husband free with the dagger, but at first he was unwilling to fight for this woman he now despised. She taunted them into fighting; a brawl that was a parody of the noble duel recounted earlier by the bandit. The husband was killed. The woman fled. Dazed, the bandit limped off with his sword and the samurai’s.

The end of the movie sees the three men at the Rashomon gates in various states of the human condition; the woodcutter’s depression about human beings, the commoner’s cynical glee and the priest’s desperate hope. Suddenly, they hear a baby crying- an abandoned infant. The commoner tries to steal its clothes and when reproached by the woodcutter, calls him a hypocrite and accuses him of stealing the samurai’s expensive dagger, which was not found at the scene of the crime. The wood cutter does not explicitly admit to the theft, but offers to take the infant into his already large family, perhaps as a penance for his lie and perhaps as a taken of his hope for human hope.

On paper, the film is little more than another statement on the contradictory nature of truth. On film, because of the cinematic qualities that grow out of the script and surpass it, “Rashomon” becomes a work of greater size. One reason for the film’s impact is its cultural accessibility; the work is intrinsically Japanese , yet not remote in style and dynamics.

… In “Rashomon” ego undelies all, the film says at last. What is good and waht is horrible in our lives, in the way we affect other lives, grows from ego; not merely the biological impulse to stay alive but the wish to have that life with some degree of pride. In Christianity, pride is the first deadly sin; but in our daily lives, Christian or any other flavor, we know that this sin is at least reliable.

We can depend on it for motive power. All of us acknowledge that we ought to be moved primarily by love; all of us know we are moved primarily by self. “Rashomon” reaches down to a quiet giant truth nestled in every one of us. Ultimately, what the film leaves us with is candor and consolation; if we can’t be saints at least we can be understandingly human.

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS