“At the very beginning of the long dialogue between thinkers that makes up western political theory there is Plato’s Republic, and at the very beginning of the Republic there is this strange and interesting exchange. Socrates asks an old man, Cephalus, if he can define justice. Cephalus says, Of course, justice means to tell the truth and to return anything you have borrowed. Socrates then asks, Suppose you have borrowed a sword from a man, and while the sword is in your possession the man goes mad. In this state of madness (mania) the man comes and asks for his sword. Does justice require that you return it?”….

Paganini was called "The Devil's Son" and "Witch's Brat" for his demonic and amazing violin virtuosity! Audiences thought Paganini made a pact with the devil to be able to perform supernatural displays of technique!

Madness, lunacy, insanity, and even extreme eccentricity have been one of the great themes of art;whether in tragic or harmless form; and dealing with some form of madness, whether by tempting, taunting or sheer accident, the edge of the abyss has always been closer than it appears in a world of mirrors and illusion. Many an uncontrollable conflagration has been sparked by innocent play with Promethean fire, from the amusing to the tragic and sometimes the absurd. Insanity can be viewed as an ecstatic dance of freedom that mimes man’s revolt against the restraints of civilization. Mostly heroes and not villains whose actions anticipate R.D. Laing’s contention that madness is often nothing more than a desperate bid for liberty.

In his psychoanalytic study of “Madness and Civilization” French historian Michel Foucault traces the middle to end of the eighteenth century as the beginning where mental images emerged, where among them “the complicity of desire and murder, of cruelty and the longing to suffer, of sovereignty and slavery, of insult and humiliation,” corresponded to the new passions of the age where the myths of a polite,perfectible society were transformed into often repulsive, strange images that were compelling, and alienating; madness has often held a deeply rooted allegoric purpose beginning the in romantic age where the artist felt an instinctive brotherhood with the madman in his isolation, which so closely paralleled his own increasing alienation from the “normal” nineteenth century world.

According to Sacheverell Sitwell, Richard Dadd was “the only good painter who worked through a lifetime of mental disease.” “The Fairy Feller’s Masterstroke”, is his masterpiece, or at least his surviving masterpiece , for Dadd lived in insane asylums nearly half a century and much of his work was lost or destroyed. The painting depicts a strange world amid the creeping vines: fallen hazel nuts and stems of grass give scale to the miniature landscape. It is populated by, among others, the king and queen of fairies, two buxom women with winged hats, an odd couple costumed in the mode of the 1840′s, and a cross-eyed gnome hunched distractedly before the “fairy feller,” whose axe will never fall. It is all as inexplicable as the title.

Born in 1817, Richard Dadd early proved to have great artistic gifts, which his adoring father had the means to encourage. The family even moved to London to enroll the young man at the Royal Academy. He was just beginning to be well known and to receive important commissions when a hallucinatory psychosis overwhelmed him. In 1843, aged twenty-six, he stabbed his father to death. Pronounced a criminal lunatic, he was locked away the rest of his life. Ordinarily a gentle man, Dadd attracted the sympathy of a physician who urged him to paint.

Among the surviving drawings is “The Child’s Problem” . In it, a crazed little boy is advancing upon his sleeping father, whose head is partially shrouded. In he background hangs an engraving, famous in its day, of a black slave begging for freedom; there is also a classical nude and a picture of a ship in a gale. The drawing surely contains a clue, however mysterious as to why Richard Dadd became a patricide.

Carl Jung, referring to the medieval concept of the daemonic, professed that “from the psychological point of view demons are nothing other than intruders from the unconscious, spontaneous irruptions of unconscious complexes into the continuity of the conscious process. Complexes are comparable to demons which fitfully harass our thought and actions; hence in antiquity and the Middle Ages acute neurotic disturbances were conceived as daemonic possession.” Indeed, prior to the seventeenth-century philosophical revelations of René Descartes–which later spawned the scientific objectivism that so characterizes the contemporary study of psychopathology–it was commonly believed that an emotional disorder, madness, lunacy, or insanity was literally the work of evil demons, who in their winged travels would inhabit the unwitting body (or brain) of the unfortunate sufferer. This archetypal imagery of invasive flying entities with supernatural powers is still evident today in such colloquialisms for insanity as having “bats in the belfry,” and in the delusional patient’s obstinate belief about being manipulated by “aliens” in flying saucers. ( Stephen A. Diamond )

Michel Foucault: "Pinel notes in passing that this Gregory had the physique of a Hercules: "His method consisted in forcing the insane to perform the most difficult tasks of farming, in using them as beasts of burden, as ser-vants, in reducing them to an ultimate obedience with a barrage of blows at the least act of revolt." In the reduction to animality, madness finds both its truth and its cure; when the madman has become a beast, this presence of the animal in man, a presence which constituted the scandal of madness, is eliminated: not that the animal is silenced, but man himself is abolished. In the human being who has be-come a beast of burden, the absence of reason follows wis-dom and its order: madness is then cured, since it is alien-ated in something which is no less than its truth. A momen

uld come when, from this animality of madness, would be deduced the idea of a mechanistic psy-chology, and the notion that the forms of madness can be referred to the great structures of animal life. But in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the animality that lends its face to madness in no way stipulates a determinist nature for its phenomena. On the contrary, it locates mad-ness in an area of unforeseeable freedom where frenzy is unchained;"...

This is not to imply that the romantics were mad, some of them were, or that madness is the prevailing tendency in their work, since there are a great many rationalist currents to be found in romanticism though distorted or manipulated. But the romantic is at least aware that he is no longer living in an age of reason, and he often recognizes some of his own features in the grimaces of the lunatic. Eventually, he may conclude that the whole of human life is madness, or that he has been born into a mad age. Romanticism had revived the ancient belief that madness is orphic knowledge. Insanity, said Charles Nodier, the teacher of Victor Hugo and Alfred de Musset, represented an upward step in the evolution of consciousness….

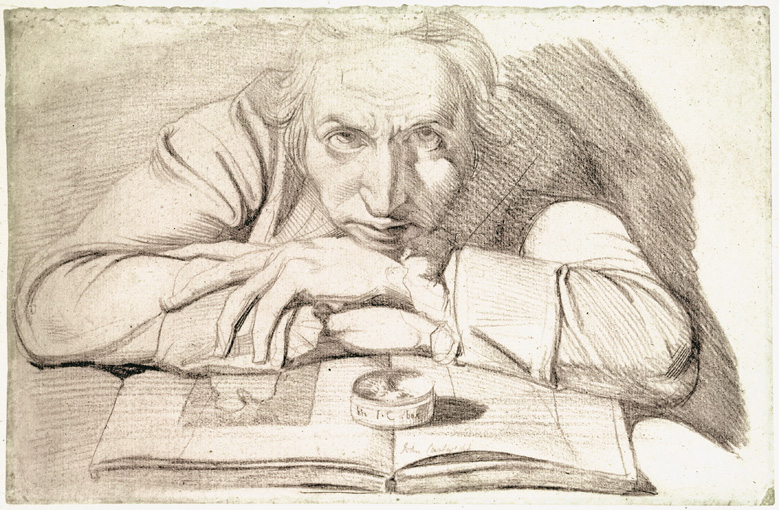

” Principal hobgoblin painter to the devil” . So said the critics of Henry Fuseli, and undoubtedly he was pleased. ” I was born in February or march,” he wrote, ” it was a cursed cold month, as you may guess from my diminutive nature and crabbed disposition.” His self portrait below, is crabbedness incarnate- beaky nose, bony fingers, bushy brows. He was known, even to friends, as the ” terrible Fuseli” , for he lived in perpetual anger. The rumor went around that he consumed a plate of raw meat each night at bedtime in order to make his dreams more fearsome. Fuseli, however, was no lunatic, and his eccentric behavior had an element of showmanship about it. He had many devotees, among them William Blake, who praised his friend in a sardonic bit of doggerel: “The only man that e’er I knew/ Who did not make me almost spew/ Was Fuseli: he was both Turk and Jew-/ And so, dear Christian Friends, how do you do?

"In this head and shoulders portrait, the sitter, presumably seated, leans steeply forward, his chin resting on his arms which lie across an open but unidentifiable book on a table. In front of him is a small round box, inscribed with 'I.C. box'. On the margin of the book, a later hand has added in pencil John Cartwright. This drawing was originally identified, on the evidence of the inscriptions, as a portrait by Fuseli of John Cartwright (1763-1808), a minor painter and friend of the artist. Comparison with other self portraits by Fuseli, and the directness and intensity of the image, make it plain that the subject is Fuseli himself. The initials on the box suggest that the drawing was made in Cartwright's house and given to him."- Tate

… And, as Jungian analyst James Hillman notes, for the almost two millennia since this distortion of the originally ambiguous daimones into evil demons, devils, or Satan, “the denial of daimons and their exorcism has been part and parcel of Christian psychology, leaving the Western psyche few means but the hallucinations of insanity for recognizing daimonic reality.” The epoch-making Cartesian approach of the late Rennaissance separated mind and body, subject and object, and deemed “real” only that aspect of human experience which is objectively measurable, or quantifiable. This advance led, notoriously, to the abject neglect of “irrational,” subjective phenomena. Descartes’ seventeenth-century breakthrough was a dubious development in human thought: It enabled us to rid the world of superstition, witchcraft, magic, and the gamut of mythical creatures–both evil and good–in one clean, scientific sweep. …

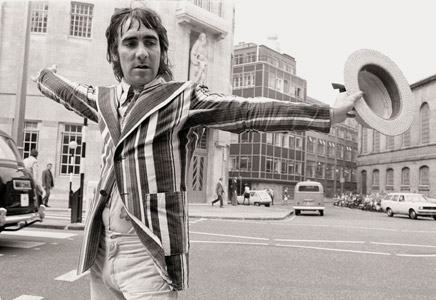

"What would you say was your most lunatic achievement? “Ah yes, that would be my birthday party in Flint, Michigan, when I was arrested by the Sheriff while in the nude covered in birthday cake. I think it had something to do with the bottle of vodka I drank at the time. “We hired this motel for the party and it got rather out of hand. Some television sets were found lying at the bottom of the hotel swimming pool and one or two of the changing cubicles were damaged. While attempting to evade arrest I tripped over and knocked out my two front teeth. “The following morning the Law invited me to get out of Flint, Michigan, and never come back, which was a bit awkward as the rest of the Who had gone on to New York and I could not get on a plane—so I hired one, a jet. That party cost approximately $25,000—everyone was very good about it!”

Fuseli shared and in large part instigated the taste for the macabre that characterized his age. “The Nightmare” was painted in 1781, and made him internationally famous. A hundred years hence, and engraving of this frightful scene was to be found in the office of Sigmund Freud, who greatly admired it. The term “nightmare” originally meant a dream of being suffocated or crushed, and Fuseli interprets this literally: a fiend is squatting on the chest of his curvaceous victim, while his horse peers wildly through the bed curtains. The physiologist Erasmus Darwin also liked the painting, so much so that he paid tribute to it in verse:

So on his Nightmare, trough the evening fog,/ Flits the squab Fiend o’er fen, and lake, and bog; /Seeks some love-Wilder’d Maid with sleep oppress’d, / Alights, and grinning, sets upon her breast.

"Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare is the consummate image of sexual terror. Ever since it was exhibited in the Royal Academy in 1782, Fuseli’s The Nightmare has become an icon of sexual terror and the night horror. The painting depicts a young woman lying in a restless sleep while an imp sits on her stomach. The Nightmare made Fuseli’s name as an artist and established his name as a painter who delighted in shocking his audiences. Fuseli’s The Nightmare has, for example, inspired writers, artists and film-makers from F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) to Ken Russell’s Gothic (1986). The Nightmare has also provoked discussion about theories of sleep paralysis and nightmares. For example, according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s International Classification of Sleep Disorders, isolated sleep paralysis, accompanied as they often are by terrifying hallucinations of demons and vampiric visitations, occur at least once in a lifetime of 40% to 50% of normal subjects."

…Demons served as ready scapegoats and repositories for all sorts of unacceptable, threatening human impulsions, such as anger, rage, guilt, and sexuality. Moreover, writes theologian Gerardus van der Leeuw, “horror and shuddering, sudden fright and the frantic insanity of dread, all receive their form in the demon; this represents the absolute horribleness of the world, the incalculable force which weaves its web around us and threatens to seize us. Hence all the vagueness and ambiguity of the demon’s nature…. The demons’ behaviour is arbitrary, purposeless, even clumsy and ridiculous, but despite this it is no less terrifying.”

Do you feel any necessity to do anything other than be a drummer—would you like to produce? “I am a producer—I’ve produced a little three-year-old daughter—Mandy. I’d like to play Hamlet but he wasn’t a drummer, was he? I suppose it could be written in that he was a drummer in his spare time—a bit of a dab hand with the sticks. Let’s face it, he must have been cos he had a sense of rhythm. “It was a bit of a fluke that I can play drums really or that I can’t play ‘em really. I’m not a great drummer. I don’t have any drumming idols—I know a few idle drummers. And they come over here after having the National Health and move in next to you. It’s disgusting, that’s what it is!”

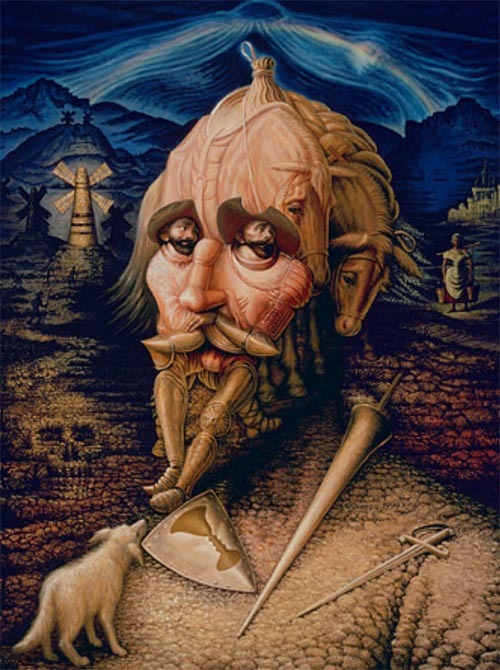

…Certainly Don Quixote’s death occurs in a peaceful landscape, which at the last moment has rejoined reason and truth. Suddenly the Knight’s madness has grown conscious of itself, and in his own eyes trickles out in nonsense. But is this sudden wisdom of his folly anything but “a new madness that had just come into his head”? The equivocation is endlessly reversible and cannot be resolved, ultimately, except by death itself. Madness dissipated can be only the same thing as the imminence of the end; “and even one of the signs by which they realized that the sick man was dying, was that he had returned so easily from madness to reason.”

"Madness was thus torn from that imaginary freedom which still allowed it to flourish on the Renais-sance horizon. Not so long ago, it had floundered about in broad daylight: in King Lear, in Don Quixote. But in less than a half-century, it had been sequestered and, in the fortress of confinement, bound to Reason, to the rules of morality and to their monotonous nights."

But death itself does not bring peace; madness will still triumph -a truth mockingly eternal, beyond the end of a life which yet had been delivered from madness by this very end. Ironically, Don Quixote’s insane life pursues and im-mortalizes him only by his insanity; madness is still the imperishable life of death: “Here lies the famous hidalgo who carried valor to such lengths that it was said death could not triumph over life by his demise.”

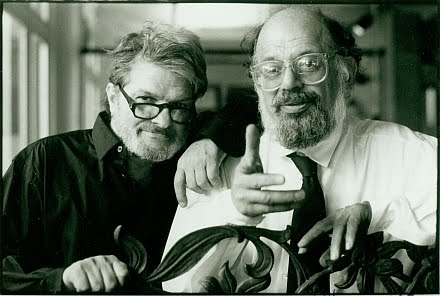

Kaddish:"It is difficult to imagine anyone actually wishing to be insane (unless this person has never met anyone truly insane). But the Beats yearned to uncover the truths that sanity masks. Ginsberg writes of the monster of the beginning womb, Burroughs of the naked lunch at the end of our fork, Kerouac of the wheel of the quivering meat conception. Birth and death, all the strange stuff in between ... we are all vulnerable together, the sane and the mad, and in the end we will all experience madness in at least some secret or small way. This poem begins as a prayer for Ginsberg's mother, but it is a prayer for all of us -- all of us together."

But very soon, madness leaves these ultimate regions where Cervantes and Shakespeare had situated it; and in the literature of the early seventeenth century it occupies, by preference, a median place; it thus constitutes the knot more than the denouement, the peripity rather than the final release. Displaced in the economy of narrative and dramatic structures, it authorizes the manifestation of truth and the return of reason.

Thus madness is no longer considered in its tragic reality, in the absolute laceration that gives it access to the other world; but only in the irony of its illusions. It is not a real punishment, but only the image of punishment, thus a pre-tense; it can be linked only to the appearance of a crime or to the illusion of a death. ( Michel Foucault )

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS