Henry Fuseli’s ghostly and frightening subject-matter was a visual continuum of the Gothic novel, which developed an aesthetics of terror and horror, was occupied with dreams and the unconscious, and often looked back to the feudal world. Fuseli once said, that “one of the most unexplored regions of art are dreams and what may be called the personification of sentiments.” However, Fuseli himself showed little interest in dreams and inner workings of the psyche, with one exception-like the Romantic writers of the younger generation, Thomas De Quincey and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Fuseli used opium….

" Fuseli himself was careful not to be tempted by "fancy" and the unknown, but believed in the possible, the probable, and the known-"our ideas are the offspring of our senses," he once said. A Sleeping Woman and the Furies (1821) took the sexual undertones even further. Now the woman is half-naked and her figure suggest that she has been violated. "

“Shockingly mad, madder than ever, quite mad!” So said Horace Walpole about a painting by Henry Fuseli. But the young Romantic Age had a penchant for madness; hence all the mad scenes that marked its artists’ revolt against reason. The art of the preceding epoch had celebrated the Great and the Beautiful. But then, almost as though the French Revolution had given the starting signal for this kind of terror as well, the rococo dream dissolves into the romantic nightmare, and the arts proceed to disgorge all the suppressed fears and ferocities of the human imagination.

"A woman's head and shoulders, simply framed in a dark background, the face twisted in her own dark torment: one imagines the haunting effect of her inner voice in Théodore Gericault's (1791-1824) The Madwoman (cover). Near the end of his short life, Gericault produced a series of portraits for Parisian psychiatrist Étienne-Jean Georget. These works followed Georget's classifications of insanity into monomanias."

It was the age that gave birth to the temperamental artist, the creative crisis, artistic bohemianism, flamboyance, and art as a “happening” and a public spectacle; advanced artists before advanced art, but also kitschy before there was kitsch.Still, they were often master storytellers who composed superb allegorical narratives backed up by figure painting of the highest quality.The times they were a’changing. it was the kitsch cult of marketing personality: the marketing of the atypical artistic personality and the marketing of the stereotypical mass society personality that effortlessly converge. Girodet, Fuseli, Delacroix, Turner, were originals; types not predicted by history, but radically change it. They also quickly become stereotypes, that is, the very model of the model modern artist, as an avant-garde personage and as a kitsch culture caricature.

"Henry Fuseli Titania and Bottom circa 1790 Oil on canvas, 2172 x 2756 mm Presented by Miss Julia Carrick Moore in accordance with the wishes of her sister 1887 Titania, the queen of the fairies, has been made by her jealous husband Oberon to fall in love with Bottom, whose head has been magically transformed into that of an ass. Bottom orders her fairies to serve his whims. Peaseblossom scratches his head, Mustardseed rubs his nose, Cobweb, standing on Bottom's outstretched hand, is ordered to kill a bumblebee. The painting was commissioned by John Boydell for his Shakespeare Gallery."-Tate

It seems no accident that the romantic age of art, the rebellion, occurred during the French Revolution, which gave a license to rebel, indeed, made rebellion popular — rebel against the old order, including the old order of art, the authority of old art, and of the art establishment, which is exactly what David was. To be romantic is to be mad, to liberate oneself from social and self-control, and to be classical means to be sane, that is, to accept inner and outer control, or at least have them as ideals. Classicism, which asserted the power and rights of the ego, became super-egoistic in neo-classicism — academicized classicism. As many scholars point out, however romantically mad they are, Girodet’s most famous paintings never entirely lose their grip on classical sanity, however much they lose their academic character.

Girodet. The Ghosts of french Heroes. 1801. "Girodet’s two paintings are not simply romantic, but, as I want to argue, they are sensational: They are the beginning of modern sensationalism -- kitsch romanticism, as it were. Kitsch means popular and mass culture, and Girodet’s two paintings were very popular, indeed, notorious crowd-pleasers, all the more so because they were "bizarre," to use Girodet’s word, or, as Bellenger said, had a "sense of mystery." They imply the same thing: The paintings were absurd. They had charismatic appeal, like Girodet himself, rather than classical appeal, like the sober academic paintings of David, his teacher. The cognoscenti may have been perplexed by their symbolism and upset by their departure from classical tradition, but the public couldn’t care less: They were thrilling. Girodet may have been an advanced artist before there was "advanced art" -- Bellenger lists his avant-garde credentials, among them the fact that he is "the archetype of the artist tormented by originality and creative innovation," that is, "the accursed artist," ..."-Kuspit

The alternative to conscious, rational control may be creative freedom, but liberty — taking creative liberty with classicism — carried too far becomes romantic lunacy. Girodet wanted artistic freedom, but in overthrowing the super-ego control of David’s classicism, he exposed the infinite madness of the unconscious. The silvery moonlight in The Sleep of Endymion is a sign of lunacy — divine madness, if you want to call it that. ( Donald Kuspit )

Girodet. The Sleep of Endymion. " Luna is the ancient Roman goddess personifying the moon, and to be a lunatic -- a devotee of Luna -- is to be moonstruck, as Endymion is. Luna is the alchemical sign of silver, and Endymion’s torso is embalmed in silvery moonlight. The lunatic light feeds on his body, as though replenishing itself, however much it remains self-generating. Girodet’s light gathers momentum, becoming more and more manic, threatening to obliterate all sense of control. All forms will completely dissolve in its delirious formlessness, which is what seems about to happen in the Ossian painting. Girodet seems to flesh out his elated phantom figures only in nominal conformity to classical demands."- Kuspit

More often, however, madness had a deeply rooted allegoric purpose in romantic art. The artist feels an instinctive brotherhood with the madman in his isolation, which so closely parallels his own increasing alienation for the “normal” nineteenth-century world. This is not to imply that the romantics were mad, some of them were, or that madness is the prevailing tendency in their work; there are a great many rationalist currents in romanticism that run counter to this one. But the romantic is at least aware that he is no longer living in

ge of reason, and he recognizes some of his own features in the grimaces of the lunatic.

"Henry Fuseli Fairy Mab circa 1815-1820 Oil on canvas, 700 x 900 mm Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington Mab is the chief fairy in folklore and literature. Fuseli's source for this subject was John Milton's poem L'Allegro (around 1630). The painter claimed that he was attempting to express 'female Nature'. Fuseli emphasises the themes of sensual indulgence and sexuality, with a fairy slumped into a bowl of junket (sweetened cream) and another little spirit holding a spoon and bowl, symbolising male and female genitals."-Tate

Eventually he may conclude that the whole of human life is madness, or that he has been born into a mad age. “I was born in 1813,” says Soren Kierkegaard, ” in that mad year when so many other mad bank-notes were put into circulation, and I can best be compared to one of them.” The comparison is not as unflattering to him as it would have been a century earlier, for the romantics had revived the ancient belief that madness is orphic knowledge. Insanity, says Charles Nodier, the teacher of Victor Hugo and Alfred de Musset, represents an upward step in the evolution of consciousness:

“Lunatics… occupy the highest degree of the scale that separates our planet from its satellite, and since they communicate to this degree with a world of thought that is unknown to us, it is only natural that we do not understand them, and it is absurd to conclude that their ideas lack sense and lucidity, since they belong to an order of sensations and comprehensions which are totally inaccessible to us, with our education and habits.”

Nodier also wrote that one meets the most reasonable people in the madhouse. This is a time honored literary conceit, even older than “Don Quixote” , and one to which most of the visionary writers were inclined to subscribe. Blake felt that way about Bedlam, and noted that “there are probably men shut up as mad in Bedlam, who are not so: that possibly the madmen outside have shut up the sane people.” A reasonably good case could be made for the thesis that Blake himself was mad, in a harmless way. He saw visions, tipped his hat to the apostle Paul, spoke of having had conversations with Milton, and drew “visionary heads” of, among others, the “Man who instructed Mr. Blake in Painting &c in his Dreams.”

Blake. Satan in His Original Glory. 1805." "If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite." (from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell) The work expressed Blake's revolt against the established values of his time: "Prisons are built with stones of Law, brothels with bricks of Religion." Radically he sided with the Satan in Milton's Paradise Lost and attacked the conventional religious views in a series of aphorisms. But the poet's life in the realms of images did not please his wife who once remarked: "I have very little of Mr. Blake's company. He is always in Paradise." Some of Blake's contemporaries called him a harmless lunatic."

At a time when the line between genius and insanity was being ever more finely drawn, madness was obviously more than just a theme for painters and poets: it became a recognized mode of romantic destiny. Friedrich Holderlin, the greatest of the German visionary poets , spent nearly forty of his seventy-three years as an incurably withdrawn mental patient. Donizetti, the composer of mad scenes in half a dozen operas, lost his mind at forty-seven and was committed to an asylum near Paris.

Thor Battling the Midgard Serpent. 1790. "In 1788 Fuseli married Sophia Rawlins, whom he used as a model in a number of erotic and macabre paintings. In Mrs. Fuseli Seated by a Fireplace (1799) she was also referred in the figure of the feared Medusa; the sight of her head turned all living things into stone. The early feminist Mary Godwin (Wollstonecraft), whose portrait Fuseli painted, planned a trip with him to Paris, but after Sophia's intervention the Fuselis door was closed to her forever. "I hate clever women," Fuseli once said, "they are only troublesome." Fuseli's 'Milton Gallery', which was exhibited in 1799, was a financial failure. Fuseli also illustrated Dante, Spenser's Faerie Queen, Nordic myths and legends, the Niebelungenlied, medieval poems, and fairy tales."

Gérard de Nerval, the French storyteller and poet, was institutionalized several times before he finally committed suicide. Robert Schumann, the German romantic composer par excellence, spent the last two years of his life in an asylum suffering from auditory hallucinations. Nikolaus Lenau, the leading Austrian poet of the epoch, died after six years in an asylum. An the Marquis de Sade, one of the great provocateurs in the underground movement against reason, spent many years of his life in prisons and asylums as punishment for private visions that proved to be far less cruel than those that became public policy under the Terror.

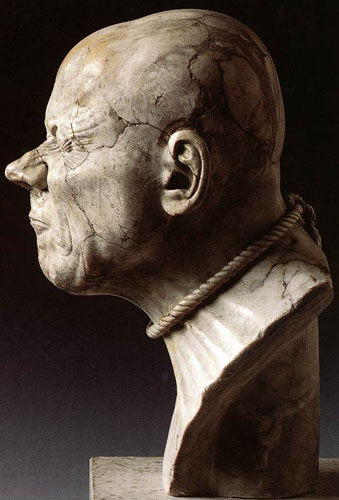

Franz Xavier Messerschmidt Character Head: The Lecher 1770-83 Marbl, height: 45 cm Österreichische Galerie, Vienna

“Girodet wanted freedom from academic control — the personal and social freedom from authoritarian rule the revolutionary emblem of Liberty embodied. But for Girodet academic classicism was not just controlled and controlling but overcontrolled and overcontrolling, and as such, creativity-stifling. To continue to be a classical artist was to commit creative suicide. For Girodet, David was a soul murderer, and Girodet rebelled against David to protect the soul of his art, and made art that murdered the soul of David’s art in revenge. Revenge had replaced envy.”

In his psychoanalytic study of “Madness and Civilization” , French historian Michel Foucault describes Sade’s case as a key to the new mental images that emerged at the end of the eighteenth century, among them ” the complicity of desire and murder, of cruelty and the longing to suffer, of sovereignty and slavery, of insult and humiliation.” In Foucault’s view, the dialectics of sadism correspond to the passions of the age: “Sadism is not a name finally given to a practice as old as Eros; it is a massive cultural fact which appeared precisely at the end of the eighteenth century, and which constitutes one of the greatest conversions of Western imagination: unreason transformed into delirium of the heart, madness of desire, the insane dialogue of love and death in the limitless presumption of appetite.”

"This is true of virtually all of Girodet’s "romantic" pictures, including such empirically descriptive works as Young Child Studying His Lessons (1800), one of the earliest attempts to articulate the mental state of a child -- another indication of Girodet’s curiosity and modernity. And genius -- he was a much more authentic, insightful genius than David, who was overly dependent on classicism and thus less trusting of emotional life, which he conveyed inadequately, certainly in comparison to Girodet. The child, Benoit Agnes Trioson, was the son of Girodet’s mentor and stepfather. The boy died young, making him all the more "romantic." (Keats, Shelley and Byron also died young.) Putting his book aside, he gazes off into the distance, thinking his own thoughts, his face radiant with consciousness. He is shown in the traditional pose of melancholy, his head resting on one hand. It is an astonishing psychological portrait, pre-dating Gericault’s portraits of the insane, which attempt to convey their mental state, but are much less convincing than Girodet’s singular portrait. All the more so because Girodet shows the boy as an individual, not as a type."

“This is why the French Revolution in its most populist phase inevitably led to the ideal of a classless society. Little did Girodet realize that when he attacked David, his artistic super-ego, he would be opening the floodgates of modern lunatic creativity — modern artistic chaos (more politely, “democratic diversity,” which means diversity without an “aristocratic” hierarchy of value, and thus with no “classical” standards of excellence) — while at the same time carrying the banner of liberty, equality and fraternity into an imaginary socialist future. And also into sensationalist mass culture, where everyone has the same right to be entertained. Girodet’s romantic paintings are, after all, still good entertainment, much more so than most movies.” ( Kuspit )

Franz Xavier Messerschmidt Character Head: The Hanged 1770-83 Alabaster, height: 38 cm Österreichische Galerie, Vienna

“Gericault’s most modern works, then, combine overcontrol and lunacy, brilliantly integrating them into romantic hyberbole. Lunacy is more charismatic than classical control, because the lunatic has clearly been traumatized, that is, has lost his reason and self-control, and thus lives in the impulsive present, which is where, unconsciously, we would all like to live, just like children. …The impulsive light in The Sleep of Endymion gives Endymion’s classical body its charismatic presence and immediacy. Classical form has no charisma — reason has no charisma. (Which is perhaps why it has little appeal.) Without the supplement of irrational moonlight — lunatic light, as it were — Endymion’s classical form lacks immediacy and poignancy, expressive power and passion, that is, emotional impact, and thus instant appeal.

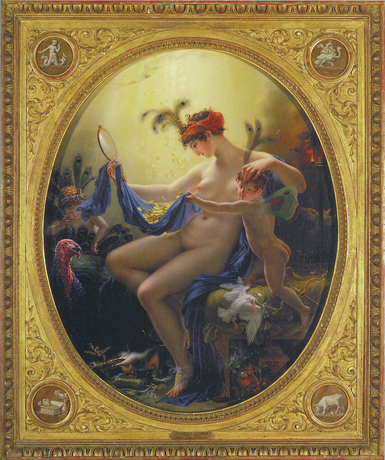

"... The body in Mademoiselle Lange as Danae (1799) also has a touch of the apparitional about it. She’s just as vain as the earlier Danae, but unlike her, Mademoiselle Lange doesn’t bestow her sexual favors unless she’s paid to do so -- a message that got Girodet in trouble with the sitter."

We can’t all be aristocrats, but we all have emotions, which is why Girodet pitched his art to the emotions, and with that, to the people. Whatever else it was about, the French Revolution was an emotional revolution. The aristocrats who ran France until the Revolution imagined they were super-egos, different in kind from ordinary egos. After all, they thought they had different blood in their veins, and the divine right of kings gave them certain rights and privileges. The king was the super-ego of France, and the aristocrats carried out his commands and enforced his rules. They were many little kings rather than one big king, satellites of the all-powerful Sun King from whom they gained their power and authority. The French Revolution was not only a revolution against an oppressive government, but also against a way of thinking — thinking that regarded some human beings as inferior by nature to other innately superior human beings. It was a revolution for humanity as a whole. ( Kuspit )

a

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS