Edmund Kean (1790-1833) was acclaimed as the greatest actor of his time. Something of a prodigy, while still a teenager he gave a command performance for King George III at Windsor Castle. Coleridge said that watching Kean perform “was like reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning.” His specialty was tragedy. On his deathbed, when asked how he felt, he famously replied, “Dying is easy; comedy is hard.” His performances in roles such as Shylock in The Merchant of Venice and Sir Giles Overreach in Philip Massinger’s A New Way to Pay Old Debts were so powerful that audiences practically rioted.

--- Keats calls Kean’s acting “perfection," and contains so much fulsome praise one wonders if Kean might have been embarrassed. Indeed, the review reads more like a fan letter than a normal theatrical review, even a glowing one. Keats ends with this appeal to Kean to take care of himself: “Kean! Kean! have a carefulness of thy health, an innursed respect for thy own genius, a pity for us in these cold and enfeebling times! Cheer us a little in the failure of our days! for romance lives but in books. The goblin is driven from the heath, and the rainbow is robbed of its mystery!” (Cf. Keats’s famous comment that Isaac Newton was guilty of “unweaving the rainbow by reducing it to a prism.”) ---

Ahead of his time in some ways, he was the first to perform King Lear with its proper ending in almost a century and a half. During all that time the play had been performed with a happy ending in which Ophelia and Lear live and reconcile. However, the public outcry was so great he had to go back to the happy version. Kean’s commanding presence on the stage is more remarkable for his having been, like Keats, physically quite small. Unfortunately, years of hard living and the use and abuse of various substances, including stimulants and alchohol, led to his early death.

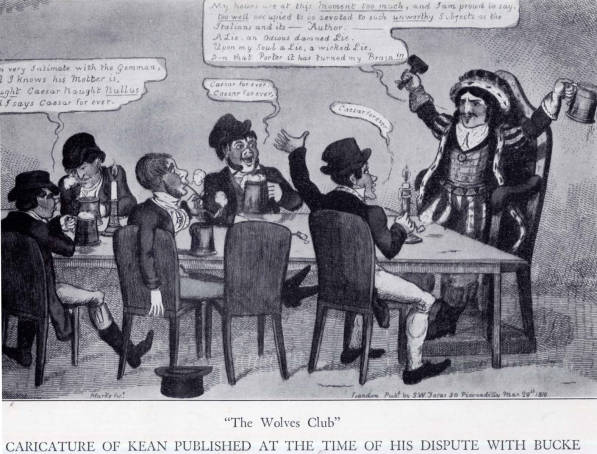

It was the trail of the splendid gypsy. Edmund Kean’s “natural” acting won the applause of Keats, Shelley, Byron and Coleridge, but it was his melodramatic life that inspired a succession of plays and even a broadway musical…

In Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night” one of the minor characters remarks, ” If this were played upon a stage now, I could condemn it as an improbable fiction.” The line might serve as an epigraph to the phenomenon of the actor Edmund Kean, a prodigious Englishman whose private life was as theatrical as his public career. Kean could be said to have originated the type of the tortured, flamboyant actor, becoming in the eyes of his generation and those that followed it an epitome of romanticism. His life has served as the material for a number of dramatists, even though some of them, like Alexandre Dumas and Jean-Paul Sartre, felt it necessary to alter details for the sake of credibility. Art, after all, insists on certain restraints that do not hamper reality.

Edmund Kean as Othello by and published by John William Gear hand-coloured lithograph, early 19th century 7 7/8 in. x 6 3/4 in. (200 mm x 173 mm) paper size

Edmund Kean was the illegitimate son of a London actress-cum-harlot named Ann Carey, granddaughter of that Henry Carey who, some claim, was the author of “God Save the King.” Kean’s likely birthdate is March 17, 1790.Charlotte Tisdwell, the remarkable woman who helped to rear the boy, remembered that she was summoned to the mother’s childbed on a St. Patrick’s Day ; and a playbill of the year 1801 refers to Kean as “The Celebrated Theatrical Child… not eleven years old. His father, also named Edmund Kean, was a surveyor’s apprentice who committed suicide in 1792. His uncle Moses Kean, who died in the same year , had been a ventriloquist-entertainer and the lover of Miss Tidswell.

Edmund Kean as Richard the Third. London, (late 19th Century) at the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C.

Aunt Tid, as Kean grew to call her, was a sensible woman and a competent supporting actress who spent forty years on the London stage. She took care of Edmund for long periods when he was a child. She provided the framework of morality from which he often wandered and the basic view of his art from which he never swerved: a passion for emotional truth.

The facts about his childhood are relatively few. he was not only taught acting by Aunt Tid, he was trained as a pantomine Harlequin, a tumbler, a singer, and dancer, and a bareback rider. It was an age that adored theatrical prodigies, and the boy made a number of appearances. Among them was a trip to Wales, where he gave a private performance of “Hamlet” for Lord Nelson and Lady Hamilton.

" width="359" height="500" />

" width="359" height="500" />Edmund Kean as Hamlet. 1814.

His adult career began when he was about fifteen years old where all acting careers began in those days, in the provinces. There were three first- class theaters in London: Drury lane, Covent Garden and the Haymarket. To appear at any other London playhouse was to get yourself blacklisted by the major theatres; and to get an engagement at one of the major theatres an actor had to prove himself in out of town theatres. Kean spent nine years in the provinces.

To some extent his physique must have worked against an earlier rise to fame. The public was used to “Roman” stars of noble presence, and Kean was short. His voice, although there are reams of testimony about its varying powers, was not a round, unblemished column of golden sound; it sometimes tended to hoarseness. His face, too, was more striking than conventionally handsome: lean, vulpine, with scowling brows and glittering dark eyes.

In addition, the style of acting he was developing must have worried some managers. It often moved audiences, but it was new and highly personal- not without poetry but much more “natural” , what we would call “realistic” , than the current fashion. London was not eager for him.

The story of his nine years in the provinces is one of grinding work, poverty disappointment, and humiliation. Explicitely the story proves his persistence , and implicitly it reveals the reasons for his growing alcoholism and other excesses. Today we can only marvel that the fire, and that is the operative word in Kean’s life, was not extinguished by heartbreak and simple hunger.

In the provincial theaters he played all kinds of parts; hoping always for the London engagement that would establish his fortunes and give the opportunity to his quality. At last the chance came, but not before some further turns of the knife. Despondent of ever reaching the three best London theatres, in October 1813,he accepted an engagement for the following January at the Olympic, a minor London house. On November 16, six weeks later, he received the long desired offer from Drury Lane. Six days later, on November 22, his cherishedd son Howard died. Wrung with grief, Kean had to trot back and forth like a hopeful dog from Drury Lane to the Olympic, begging the Olympic to release him and Drury to be patient. The tangle was finally cleared; his Drury Lane debut was set for January 26, 1814, as Shylock.

Theatres operated differently in those days. Their closest modern parallels are opera houses where a permanent company would engage a visiting artist. An actor like Kean would arrive a day or two ahead of time with his own costumes, go through a minimal rehearsal to establish outlines of movement, which varied little from theatre to theatre, and then would appear. A “directed” production, in our sense of the word, was virtually unknown; audiences went to see individual performances.

History is lucky as far as Kean’s London debut is concerned. On that bleak winter night, William Hazlitt, jewel among critics, was present. There were, he said later, about a hundred in the pit, for Drury’s business had fallen off. Kean’s engagement was in fact one of several desperate attempts to find an attractive new star:

Keats:Mr. Kean’s two characters of this week, comprising as they do, the utmost of quiet and turbulence, invite us to say a few words on his acting in general. We have done this before, but we do it again without remorse. Amid his numerous excellencies, the one which at this moment most weighs upon us, is the elegance, gracefulness and music of elocution. A melodious passage in poetry is full of pleasures both sensual and spiritual. The spiritual is felt when the very letters and points of charactered language show like the hieroglyphics of beauty:- the mysterious signs of an immortal freemasonry! ‘A thing to dream of, not to tell!’ The sensual life of verse springs warm from the lips of Kean, and to one learned in Shakespearean hieroglyphics, - learned in the spiritual portion of those lines to which Kean adds a sensual grandeur: his tongue must seem to have robbed ‘the hybla bees, and left them honeyless.’

Edmund Kean made his triumphant debut as Shylock in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice at Drury Lane Theatre. ‘If I succeed I shall go mad,’ he had said. To the amazement of the rest of the cast he abandoned the traditional red wig and wore a black wig and beard. When Kean got home, flushed with success, he said to his wife: Mary, you shall ride in a carriage yet and Charley [his son] shall go to Eton.’ The Times was unequivocal: ‘We have seldom seen a much better Shylock.’ The general consensus was that, ‘For voice, eye, action, expression, no actor has come out for many years at all equal to him.’

His Jew is more than half a Christian. Certainly our sympathies are much oftener with him than with his enemies. He is honest in his vices; they are hypocrites in their virtues … His style of acting is, if we may use the expression, more significant, more pregnant with meaning, more varied and alive in every part, than any we have almost ever witnessed. The character never stands still; there is no vacant pause in the action; the eye is never silent.

- William Hazlitt, Morning Chronicle

In many an actor’s life the interest of the story would dwindle here. A struggle for recognition- but afterward just a straight, climbing line of success. The success certainly came. Through the years he essayed the great parts, one after another: Richard III, Hamlet, Othello, Lear, and some lesser but rewarding roles like Sir Giles Overreach in Massinger’s “A New Way to Pay Old Debts”. He was received better in some than in others, but he became the darling of Drury, of London, of Britain. By 1816 a London newspaper said that Englishmen had stopped talking about the weather when they met in the street; instead they asked each other what they thought of Kean’s Giles Overreach.

But the marks of his struggle, his chancy boyhood and youth, had not been erased. He drank, he gambled, he roistered. His marriage, which had never been good, grew worse now that poverty did not chain the pair together. Perhaps worst of all was his realization that not even reaching the pinnacle of his profession would bring him social acceptance; perhaps in part because his natural father Aaron Kean, was a Jew which explained the allusions to Kean’s physiognomy by writers at the time. In the theatre he was imperial; in a ballroom, to which he might have been invited as an amusing curiosity, he was, as the law once put it, a rogue and vagabond.

Kean was an abnormally sensitive man of whom it was said that he could see a sneer across Salisbury Plain. To live in a stratified society and be treated as a lackey by his intellectual and spiritual inferiors was a very hot and real hell for Kean.

…”the tumult and conflict of opposite passions in the soul.” Here, Hazlitt is seeing and describing something which Eli Siegel was to make clear for the first time in history in his principle: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” Two great opposites in Kean’s acting are passion and control, and these are throughout an essay which Mr. Siegel said is “The most valuable description of acting perhaps in the world,” by the American writer, Richard Henry Dana. Dana saw Kean act in what Mr. Siegel referred to as “careful Boston” of the early 1800s, and felt the honesty of Kean changed him, made him a better person. He says that to see Kean was an “intellectual feast,” and writes:

In his highest wrought passion, when every limb [is] alive and quivering, and his gestures…violent, nothing appears ranted or over-acted; because he makes us feel that, with all this, there is something still within him vainly struggling for utterance….[he] runs along the dizzy edge of the roaring and beating sea, with feet as sure as we walk our parlours.

Commenting, Eli Siegel described the essence of Kean’s appeal when he said, “He makes us feel art consists of hanging about necessary precipices that you never jump over.”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS