“There’s no one more punctual than a woman one doesn’t love” ( “Kean” by Jean Paul Sartre )

From its declining fortunes Drury Lane Theatre was to be rescued, briefly, by the arrival of Edmund Kean, the most fiery and thrilling actor of his day. His passionate and naturalistic approach to Shakespeare gave audiences a sense of excitement that they had never had from the noble performances of the Kembles. At the age of twenty he had played leading parts with Sarah Siddons, who, though she recognised his ability, disliked him, describing him as “a horrid little man”, and saying that “there was too little of him to make a great actor”.

Mulrooney: Educated to an understanding of Kean by Hazlitt's theatrical criticism, Keats's attention to the actor in letters and theatrical reviews in late 1817 and early 1818 coincided with and, I will argue, occasioned his thoroughgoing revision of the poet's role as a cultural intermediary for readers. In contrast to the self-assured demeanor embodied by Smith, Hill, and DuBois, Keats imagines the poet continually engaged in an identity crisis brought on by encounters with actual and imagined cultural objects. The poems of early 1818, especially, begin to reshape contemporary notions of authorship because they present the poet speaking from--rather than merely reflecting on--the uncertain moments that characterize such encounters.

For the finest artistic minds of the time, Kean was for them the embodiment in the theatre of romanticism- that movement in which art tried to attain universals through the closely examined adventures of the individual soul. To contemporary poets and visionaries Kean’s acting was, in Hazlitt’s phrase, “An anarchy of the passions,” a revolution for which they hungered and which he demonstrably abetted. A central issue with Kean, and what had fascinated the Romantics, particularly John Keats and Byron was that Kean became the roles that he had played; that is he eventually no longer distinguished between private and stage selves, chiefly because the public would not allow it for social reasons. The major theme of Edmund Kean was that of imposture or playacting. His story is that of self identity related to the question of appearance versus reality, identity, authenticity, and social alienation. Jean-Paul Sartre described Edmund Kean as “the actor who never stopped acting”.

Kean had been touring the country getting work where he could when he was brought in by the Drury Lane management simply because he would not have to be paid too much, yet his debut on 26 February 1814 is one of the great legendary nights in the history of British theatre. The play was The Merchant of Venice and the obscure provincial actor audaciously playing Shylock in a black wig instead of the traditional red one, took the house by storm. By the time he reached the great rhetorical scene in Act III “If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh”? the audience were on their feet to respond to each passionate question with roars of approval and at the end of the performance it was clear that a great new star had risen on the London stage.

“Kean’s conspicuously vexed relationship to the situational possibilities offered by the dramatic text was, in Hazlitt’s apt formulation, a “radical” departure from John Philip Kemble’s personification of rhetorical mastery. Whereas Kemble’s excellence resided in a demonstration of the single emotion called for by each dramatic scene, Kean attracted audiences with an ability to present, in a moment, a mass of contradictory feelings. With his pantomimic contortions and emotional outbursts, Kean imported an “illegitimate” grammar of representation onto the Drury Lane stage, rendering the traditional relation between performer and audience uncertain and exposing the legitimate theater’s increasing commercial reliance on lower-class modes of consumption.”( Jonathan Mulrooney)

Acting, then,within the context of Romanticism, is seen as an essential element in social interaction. Kean goes so far as to suggest that there is no moment when he is not acting, i.e. giving a measured and conscious response to a situation, where he is aware of the effect of the words he chooses to use and the way in which these words are delivered.

The full title of the Jean-Paul Sartre of play of 1953 is “Kean or Disorder and Genius”. There is certainly room for speculation as to whether “real” life is seen as disorder where emotions and desires may impede or infringe upon the actor (player) – where others may exercise a degree of control over the player, perhaps simply by virtue of the fact of being there. Kean feels most at home when acting and therefore when he is on stage. If “real” life is disorder where authority and control cannot be guaranteed, is the stage genius where Kean can exercise complete control and cause the audience to feel what he wishes them to feel? By extension it could be argued that if a play is well written, it is the reality, presenting distilled truths about life, while life is the “rehearsal” during which we practise and try to attain elements of truth.

''Kean'' de Jean Paul Sartre:With entirely apt irony Kean plays the final scenes of "Othello" in the presence of the Prince of Wales and Elena, who knowingly provokes immense jealousy in Kean by chatting to and flirting with the Prince of Wales. This prompts Kean to lose control of his performance and allows Kean the man to take over. At one point he discusses the situation with the audience and informs them that he, Kean, does not exist - only his performance exists. As an actor, Kean must have immense understanding of humanity and emotions. Not only does he use this understanding to portray characters on stage, he uses the same skills to manipulate situations in society. However, in order to achieve this objective he must remain in control, judging what to say and how to say it in order to achieve the desired effect. Jealousy, however, interferes with this skill as emotions are engaged and prevent the mind from judging the situation with clarity. In this situation (of jealousy), Kean loses control - the "I" guiding the performance is lost as he reacts to his own emotions rather than manipulating those of others. He is no longer in control - others are controlling him, prompting him to conclude that he does not exist.

Indeed Sartre, through extrapolation of Kean, asserts that the actor has gone so far as to suggest that what is “real” is simply badly acted, implying in the play that acting belongs to a much bigger stage than that of the theatre.Of course, as he has shown in his pursuit of Elena,his love interest, he adopts a persona to appeal to women. He plays a part in order to try to win them over, and it is the image for which these women fall. Kean is now so used to adopting this persona that he is no longer sure where the image ends and the man begins. Indeed at one point he even states that he is playing the role of Kean.

Here we are touching on what is one of the main points of Sartre’s narrative an ongoing fixation. Sartre seems to be suggesting that in society we adapt to the company we keep and play parts or adopt different personas according to the different situations in which we find ourselves. Others, who are in the same position, help decide one’s reaction; and indeed ultimately one’s fate, while

playing the same “game”.

Another major point is the nature and role of love in this process. Kean has pursued Elena not just because of her physical

beauty, but because she has shown the proper, as he sees it, appreciation of his talents.A shameless groupie. He is not, therefore, driven by some selfless and hopeless love for another, but rather by a desire to be loved by one who would appear to be besotted with him. His love, and by inference by Sartre, is that all humankind’s love is in the main, ego-driven. Elena, it should be said, is equally keen to be the focus of Kean’s attention.

Jane Austen:Jane Austen saw Edmund Kean a little more than a month after his astonishing first night and he was very much the talk of the town. Such was his popularity that Henry could get only a third and fourth row (though in a front box). Jane thought that it would be a ‘good play for Fanny’ and that her young niece would not be ‘much affected’. Her reaction in a letter to Cassandra the next morning was one of measured enthusiasm. We were quite satisfied with Kean. I cannot imagine better acting, but the part was too short and excepting him and Miss Smith – and she did not quite answer my expectation – the parts were ill filled and the play heavy. I shall like to see Kean again excessively and to see him with you too, it appeared to me as if there were no fault in him anywhere and in his scene with Tubal there was exquisite acting.

…A theatre critic of the day, Hazlitt, wrote “for voice, eye, action and expression, no actor had come out for many years at all equal to him”. Edmund Kean’s natural acting won the applause of Keats, Shelley, Byron and Coleridge. All the romantics were on the trail of the splendid gypsy.It is easy to see Kean’s life as a mass of uncertainties as to what may ensue: things could so easily topple into forced, failed semi-jollity saved only by the verve of his actions as he himself embraces the clichés and the parodies of his life in which he neither stands off from the material nor is capable of bludgeoning it to death a departing on a new tangent. As Kean was an infernal hell-raiser, so we can always take a devilish pleasure in his cavortings. The tragedian was most famed for his dark, brooding Shylock, but the Shakespearean character at the heart of his life’s performance may have been a tragi-comic incarnation of Puck; his mischief infected audience and cast alike…

In 1817, the rivalry between the two national theatres ran so high, that the Covent Garden management employed agents to scour the provinces in search of a rival to Edmund Kean at Drury Lane. After a time one was found in the person of Lucius Junius Booth, who in stature, rôle of characters, and (as it was imagined) style of acting, closely resembled, if he did not equal, the great original. He made his début at Covent Garden, in the character of Richard the Third. Whether it was a success or not seems doubtful; for the manager being out of town, those deputed to act as deputies did not care to undertake the responsibility of engaging the new star. In this dilemma, overtures were made to him by the rival house, which he accepted, and made his appearance as “Iago” to Kean’s “Othello” to a densely-packed audience at Drury Lane. So great was the likeness between the two actors, that strangers were puzzled to know which was Kean and which was Booth, until the tragedy reached the third act, when the genius of Kean made itself felt, and no doubt remained in the minds of the audience which was master of his art.

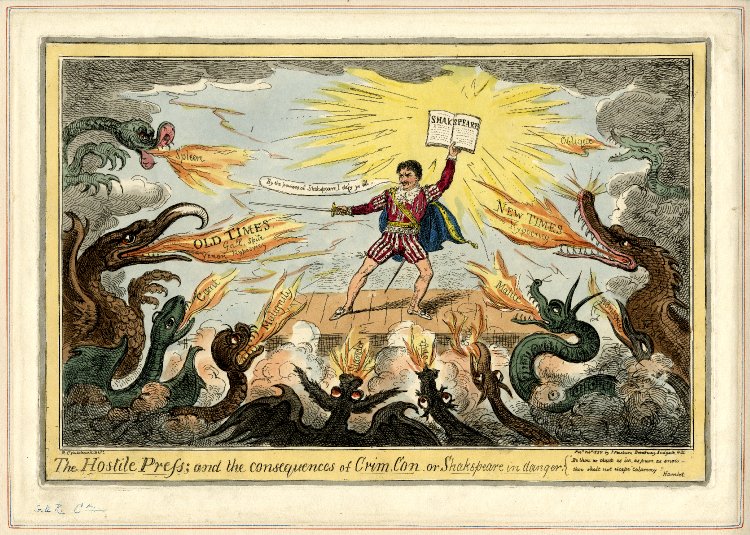

Robert Cruickshank. Edmund Kean.The hostile press; and the consequences of crim. con. or Shakespeare in danger, 1825

Although critics like Hazlitt’s tastes and sympathies threw him much in the society of actors, such as Keans, eventually pushing the limits caught up with Kean; by 1824 the thoroughly Bohemian Shakespearean was mulcted in £800 damages, in consequence of a disgraceful liaison with the wife of Alderman Cox; and while audiences thronged the one theatre to testify their sympathy for a favourite and popular actress, they crowded the other to howl and hiss at the thoroughly disreputable and disgraced tragedian.

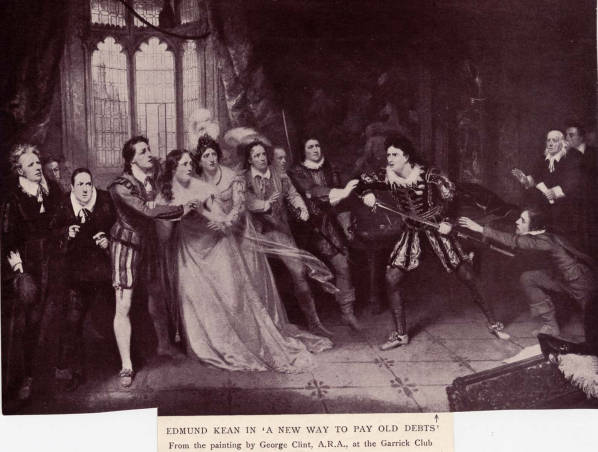

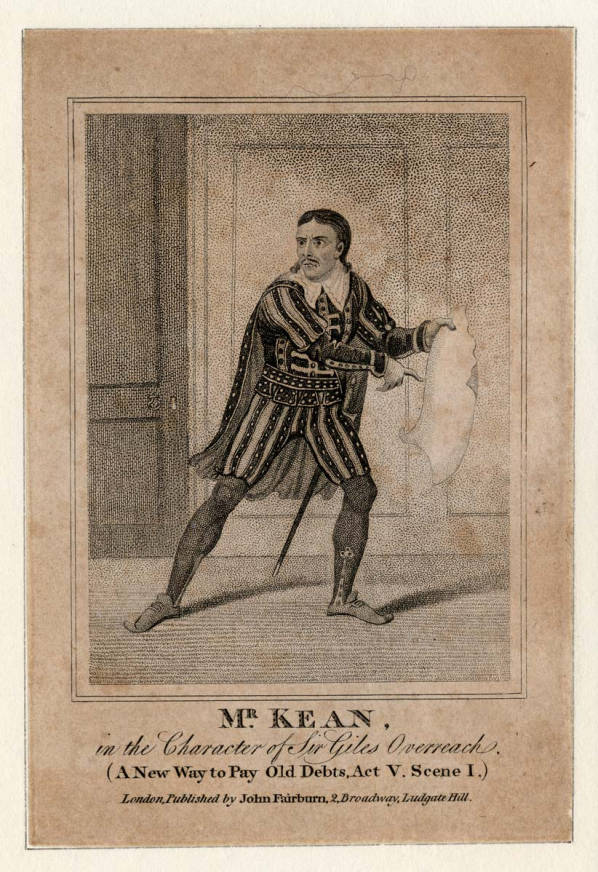

Still, Edmund Kean had restored the fortunes of the Drury Lane theatre, literally resurrecting it from the jaws of bankruptcy, and creating a whole new clientele. In quick succession he played Richard III, Hamlet, Othello, Iago and in 1816 he persuaded Drury Lane to put on a new play, Massinger’s A New Way to Pay Old Debts in which he played the villain Sir Giles Overreach. The sense of evil in his performance was so disturbing that many present at the first performance had to be removed in hysterics, Lord Byron had a convulsive fit, while many of Kean’s fellow actors were terrified. He was to triumph there for several years until eventually his new found success and prosperity, acting on an unstable and anguished personality, tragically led him to drink and to run up large debts.

Theatre play ''Kean'' de Jean-Paul Sartre:Yet, in spite of his apparent control and insouciance, Kean needs to be loved. He feels the need to prove himself and to be appreciated, perhaps even to be given some kind of validation through the love of women. Two things seem to matter to him - acting, and his "reward" in the form of love or adulation. Money seems to count for very little. A key phrase in understanding Kean's character (and by extension all of us who form society) is "So much pride (amour-propre), so little self esteem." Love, or perhaps rather (and quite crucially) being loved is what keeps Kean going - he requires some form of appreciation in order to make him feel worthwhile.

Kean, to avoid the hostility after the Cox case, decided wisely to give the ostentatious moral outrage time to subside while he toured America, which went over fairly well; his bad boy reputation preceded him, only adding to the aura and contributed to restoring his finances and confidence. After more than a year’s absence he returned to England to find that the public had forgiven him, and he was a darling of the crowd once more. But his health, ravaged by drink, work and temperament was declining. He had frequently to cancel engagements, he could not learn new plays, and sometimes he even “went up” in old parts. Still he blazed, fitfully but forcefully, up and down Britain and on his one professional visit to Paris. He collapsed on stage in 1833, acting Othello with his reconciled son Charles, as Iago. Unconscious, he was put to bed in a nearby tavern and a few days later moved to his house in Richmond. He died there in May, aged forty-three. In another room of the house lay his battered old harridan of a mother, to whom he had recently given shelter. She died twelve days later.

Despite the quality of Sartre’s and Dumas’s versions of “Kean” and its existential characteristics and sheen- a man hovering between realities, aware that the adulation he receives is paid to the less real of his selves; a man tormented by internal conflict into a keener awareness of the anguish of existence- The real Kean, although his actions often superficially resembled those of the fictional one, the mythical one, was the protagonist of a tragedy, not a romantic melodrama.

Kean juggled his assignations, boozed with his cronies, insulted his audiences as the fictional Kean does, but unlike the play, there was never even hint in all this of lightheartedness, of true gaiety.Kean’s sense of humor was limited and bitter. It is the frenzy of a man none the less sentenced for being self-sentenced. Among his papers was found an introspective poem with the lines:

“Whipt in his childhood, in manhood trained, In all the vices which the fallen strained”.

ADDENDUM:

…he is the sort who ( “plays himself at every second. Its a marvelous gift and a curse, at the same time: and he’s the real victim of it, never knowing who he really is, whether he’s playing or not playing…(He) even plays his own life, no longer recognizes himself, no longer knows who he is. An who, in the end, is no one”). Acting is not self-expression but self creation, in an almost dialectical movement of reconciled contraries, but which has no permanence. (“One doesn’t act to earn one’s living. One acts in order to lie, to lie to oneself, to be what one cannot be and because one has had enough of being what one is. One acts in order not to know oneself and because one knows oneself too well. …One acts because one loves the truth and because one hates it. One acts because one would go mad if one didn’t act. Act!… He recognizes that even his love for Eléna is illusionism. ( Jean-Paul Sartre, Harold Bloom)

COMMENTS

COMMENTS