The forbidden world of Watteau. The witness of a life he could not share; one of France’s greatest painters transformed reality into the most poetic and lyrical visions in the history of art….

“This artist who said hardly anything about his paintings and struck most of his friends as something of a mystery man took as his essential subject the invention of self-consciousness, the struggle to feel fully alive.” … In its best sense, Mr. Perl sees the birth of the modern in Watteau’s figures awakening to their own imperfections. “Watteau’s young people seem to want, above all else, to feel at ease, somewhat at ease, in an uneasy world,” he writes. In work such as Watteau’s famous painting of “Gilles,” the contemplative clown, Mr. Perl finds “doubts,” though they are “clothed in the commedia dell’arte lightness of an improvisation or a folly.” He calls Watteau “The man who practically invented the bohemian imagination.” In his aesthetic wanderlust, his reveries of vagabond performers, Watteau did not follow the dictates of the church or a rich clientele, but pursued art for art’s sake, the prototypical modernist.

Georgia Cowart:Like Watteau's fetes galantes, this genre has been linked to the frivolity and degeneracy of an aristocratic elite. Yet a careful study of specific works, along with their parodies at the Comedie-Francaise and the popular theaters of the foire, reveals how the opera-ballet sets up a discourse of subversion successfully engaging a discourse of absolutism found in the entertainments of Louis XIV's early court. Two works in particular, Le triomphe des arts of 1700 and Les amours deguisez of 1713, give meaning to the sacred island of Venus as a political utopia and as a direct challenge to the absolutism of Louis XIV.

Eighteenth-century France, considered either as an ideal society devoted to pleasure and aesthetic cultivation or as a less than ideal society given over to libertinage and dilettantism, had its life span shortened at both ends. Beyond term and groaning not with labor pains but with boredom, it had to wait for Louis XIV to die- fifteen years after 1700- before it could be born, and it lost its last decade when another society put it to the guillotine. “Do get on with it- things are so dull.” the court might have said to their dying monarch; three-quarters of a century later Mme du Barry cried out on the scaffold, ” One moment more- life is so sweet!”

Watteau. Gilles. According to one of his patrons, Watteau was only rarely satisfied with his own canvases. Today these are considered , almost without exception, to be among the most memorable creative achievements of the eighteenth century.

Earlier, Mme de Pompadour had had the perception to make her sinister prophecy “Aprés nous le déluge.” but that lady’s favorite painter, Boucher, offers nothing more revealing than skilfully enameled surfaces celebrating the niceties, albeit with an occasional lapse into the vulgarities, of established taste. Eighteenth-century France found no social critic among artists, as did eighteenth-century England in that vigorous protestant against the evils of the day, Hogarth. But France did find an artist great enough to distill the virtues of its privileged society into an ideal expression. He appeared early, during the first decade of that society’s existence, but remained an observer from outside, as if he sensed that the corruption inherent in the ideal must affect anyone who was fully a part of the game. This was outsider Jean Antoine Watteau ( 1684-1721 ).

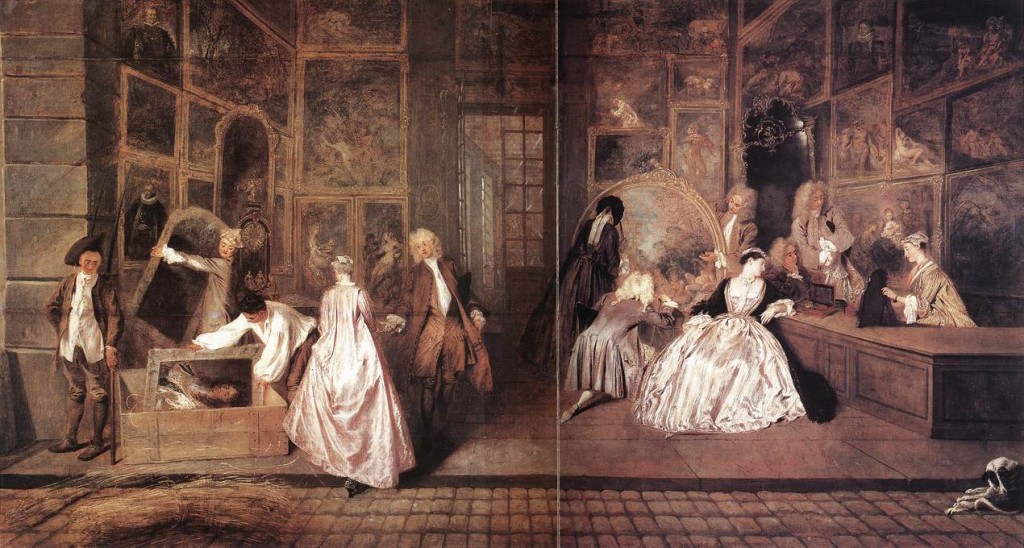

Watteau. The Shop Sign of Gersaint. Lisa MacDonald:One of his most famous works was produced in only eight days. It was created for Watteau's friend and art dealer Gersaint. Le Enseigne de Gersaint (1720) is a tour de force of Watteau's draftsmanship and his skill as a colorist. This painting is believed to be a sign which hung outside Gersaint's shop. It is an excellent example of genre painting for here we see the everyday life of the townspeople and we learn that Gersaint sold paintings, framed mirrors, and toiletries for a refined, aristocratic clientele. Perhaps Watteau was compelled to became a chronicler of everyday life because for him it was natural, and therefore truthful and honest. This new attitude is representative of the humanistic ideology of the 18th Century but it was Watteau whose art embodied and propelled a more humane attitude toward genre painting and common man. It was a time when grace and elegance were held in high esteem while at the same time Revolution and industry seemed to be wiping away these very same ideals.

Three painters neatly spaced into successive generations: Watteau, Boucher, and Fragonard; recorded the ideal promise, the surface triumph, and the lively decline of this society, without inreoducing so much as a hint that it was faulty and threatened by revolutionary philosophies. At its end, when the foundations were eaten away, Fragonard was still romping exuberantly about it in the decayed structure as if it wwere perfectly sound; although we, by forcing hindsight a bit, can read into his art the symptoms of the fall, no world on its last legs has ever been presented more attractively by a particiapnt who enjoyed its pleasures with less question.

Watteau's chalk drawing of a flutist and two women is one of a large number of life studies that he made with no defined purpose in mind. These he kept in bound books, later using the figure in various combinations as models with which to people his painted landscapes.

All Watteau’s surviving paintings were done during the last twelve years of his life, which means the six years before the death of Louis XIV and the six after. The chronological sequence of these paintings cannot be worked out with much certainty, but Watteau’s mature style, the apotheosis of the century’s ideal, was born during the middle years of the twelve from the conjunction of three circumstances: the death of the old king and the consequent release ogf the new century; Watteau’s adoption as protegé by the immensely rich Pierre Crozat, which placed him in a position to observe the new society intimately; and the appearance of the first strong symptoms of tuberculosis, which intensified the poignantly withdrawn nature of his spirit, and which eventually killed him at the age of thirty-six.

Watteau. Le Mezzetin.James Panero:Mr. Perl is not the first to take an unorthodox approach to his history of this artist. Watteau's most successful biography, Mr. Perl recounts, came out of a fictionalized memoir by Walter Pater calle

uot;A Prince of Court Painters," which was published in 1885, and which, "in assembling and readjusting some of the facts of the artist's life ... constructs a fable about Watteau that is truer to what we feel when we're looking at his paintings and drawings than a more straightforward account could possibly be." In his story, Pater "imagines himself as a part of the eighteenth-century Pater family that actually knew Watteau."

Surely we may assume that the dreamlike quality of Watteau’s art – its quiet, half-melancholy languor, the impression it gives of having been created by a non-participant from an observation point just outside the borders of life, is seemingly connected to his frailty. He seems to understand what the passions of men and women are, yet he must reduce the tempests of physical love to a sweet, regretful tenderness. The sexual games are refined to graceful suggestion; the bacchanal becomes a stroll in a shaded park; the delights of the flesh are recognized and perhaps yearned for, but their consummations are abjured from the beginning.

The murmured endearment must do for the amorous lunge, even for the caress. When a lover occasionally yields to impulse and commits a preliminary “faux pas” , he disrupts the reconciliation between the abstract desire and physical potential that holds Watteau’s world together so harmoniously, but so tenuously, against all the natural violences of life. It is a nostalgic world whose fragile denizens, shimmering in taffetas and satins as they wander through it, seem to look back upon the fullness of lost pleasures that, in truth, they have never experienced.

Watteau. Love in the Italian Theater. "It is easy to dismiss Jean-Antoine Watteau as the Barbara Cartland of early 18th-century French painting. That would be a mistake. True, his bucolic idylls of courting couples and little lapdogs have a domestic theatricality that has fallen from fashion, but they are unique for their wistful mood about melancholy and the transient nature of love. And there is a sensibility that anticipates the art of the future by painters like Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse Lautrec--of art being about art, the world of art as seen through the eyes of an artist."

It is odd to discover comments made by his contemporaries that this most poetic artist of the eighteenth century was thought of as a realist. Etienne Jeurat, a genre painter who engraved some of Watteau’s works, could make the closest possible translation of these almost ethereal visions and still admire Watteau as a painter who “marvelously imitates nature.” If the comment seems implausible to us, who have seen the nineteenth-century’s demonstration of what the close imitation of nature can mean, it does make one look at Watteau a second time from a different angle and calls our attention to an element in his art that is usually taken for granted.

In one context of his time, Watteau was not only a realist but innovational in his realism. He anticipated the impressionists’ use of the visual world as one vast snapshot, whose bits and pieces could be painted, with no matter how much calculation, to reveal the essential character of a scene, a person, or an object,through its casual surface. If Watteau’s world is an invention and a lyrical dream, and if the people who move within it are variants of a human race more fineboned than birds and as exquisitely plumaged, he pictured that world as the impressionists pictured theirs, in its momentary, unself-conscious aspects, with its denizens unknowing, or not caring, that they are observed.

Watteau. Les Cahrmes de la Vie. Julian Bell:Artists came to see that his canvases were joyful in their very absence of academic method -- in the way that Watteau freely slung together sketches from his stash that happened to fit in order to get a composition going. A wider audience came to see that they were joyful in their avoidance also of academic subject matter. Rather than some solemn Wrath of Achilles, say (a theme deemed proper around the same time by Antoine Coypel, the director of the Academie), Watteau was painting guitars and masks and taffeta, fans and bouquets, comical lechers, pretty girls galore -- above all, love. In fact here was, as it turned out, the pictorial apostle of the great rush to hedonism that French society permitted itself after Louis XIV finally expired in 1715 -- the period known as the Regency (since the new king was in his minority), marked by its reckless free-spending, constant partying, and satire, with the banned commedia dell'arte returning to town.

Watteau’s genius for observing the casual gesture; the turn of a head, the lift of an arm. the stance of a body as it conforms to the balances of walking, sitting, or playing a musical instrument; and his sensitivity to these unstudied attitudes as revelations of mood and character are apparent throughout his paintings, but such gestures are most wonderfully set down in his drawings. He made of drawing something that it had never been before, something barely related to his contemporaries’ idea of drawing- in terms of musculature academically rendered, of the invention of posturings and proportions in which the body becomes a machine adaptable to the contrivance of compositions in the grand manner- or indeed to the idea of drawing as a memorandum of facts for later reference. Even genre painting, with its basic premise of eching daily life, was a matter of setting a typical, explanatory, narrative pose, which in being once removed from the spontaneously assumed attitude might be entirely removed from immediate perception and expression.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), Woman Lying on a Sofa, c . 1717–18, red, black, and white chalk, 21.7 x 31.1 cm, Fondation Custodia, Paris

Watteau was so indifferent to these conventions, so alone in his use of drawing as the expression of intimate response to observed objects, that twenty-seven years after his death, in a lecture before the Academy, his good friend the Comte de Caylus asserted that Watteau “knew nothing about anatomy” because he seldom drew from the nude. But no draftsman has more beautifully integrated the structure and movement of a body, clothes or unclothed. Caylus could refer to Watteau’s “inadequacy in the practice of drawing” only because Watteau did not draw in the heroic manner.

No doubt it is true that if Watteau had attempted heroics he would have been lost, but nothing could be more beside the point. With the possible exception of the eccentric Renaissance Italian Jacopo da Pontormo, who is probably in a class outside any other, Watteau is the first modern draftsman, the first artist whose informal sketches can be appreciated in terms of an independent art that is as revelatory as painting. Yet even here, in his most personal work, Watteau holds himself aloof. He is the most sensitive of observers, but never a participant.

ADDENDUM:

Watteau’s deliberate unreality and gentle melancholy also implied a larger world beyond private leisure and the pursuits of pleasure. Here, on a more implicit level, was at least a hint of the alienation of court elites from political life, from larger responsibilities, commitments, and some sense of a larger social awareness. Here, at an early stage in the Rococo, court’s art new alternative to history painting showed, perhaps, some slight consciousness of the psychic costs incurred in the retreat from public life into private pleasure. This too, would disappear once the Rococo was taken up by the monarchy, once the Rococo was reformed by those with the power to imagine no greater authority or reality other than their own lives. If the highest official discourse always tends to project a relatively unambiguous image of prevailing order, justice, and harmony – think of the happy spin every ruler or administrator tends to put on their official pronouncements – it is not surprising that the appropriation of the new Rococo style as an official, royal, state style around 1740 also involved a considerable reinterpretation of that style from the more ambiguous art of Watteau to the innocent, carefree delights of Boucher. As a state style, Boucher’s Rococo banished all self-doubts and internal conflicts, all melancholy and regret, all potentially disturbing or distracting self-consciousness of finitude and illusion. ( Robert Baldwin )

COMMENTS

COMMENTS