… or agonies in the Garden.He antagonized conventional orthodox theology. Mantegna was one of the most important historical thinkers of his time. He brought to his understanding of painting as historical narrative, a new sense of the past, like that which has been shown to be the essential contribution of Renaissance humanism to the study of history.In addition, his deeply imbricated sense of time led him to manipulate the temporal structure of a pictorial narrative. …

Mantegna. The Calumney of Apelles.In the seventeenth century, Rembrandt made a copy of Mantegna's drawing when it may have been in his own collection, and Rembrandt's copy is now also in The British Museum.

Andrea Mantegna, the early Italian Renaissance master, is not an artist whose work goes down easily. Before he reached the age of twenty, Mantegna was already being praised for his “alto ingegno” -exalted genius-, and he became the court artist for the Gonzaga family in Mantua before he was thirty. Yet, Mantegna was not simply a great painter. Together with Donatello, he was one of the defining geniuses of the 15th century: the measure of what an artist could be. His highly original and deeply personal vision, the descriptive richness of his pictures, and his biting, hypercritical but always exalted mind gave Mantegna’s art an extraordinary edge and earned him a preeminent place in the Renaissance. …

---"Bacchanal with a Wine Vat and the companion Bacchanal with Silenus, also in our collecion, were inspired by the designs of Roman sarcophagi once in the collections of the Della Valle family and in the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. While demonstrating Mantegna's refined knowledge of antique sources, these engravings above all attest to his boundless imaginative powers in reshaping imagery for a uniquely personal artistic vision. Here, the drunken heroic figures gather around the wine vat populating the space with a funereal majesty—it conjures the deeper emotive content in the ancient associations between Bacchic rites and Christian mysteries. The unconscious youth at the center is held up by a gaunt mourning figure much like the dead Christ in the Pietà. Metropolitan

Mantegna is never eccentric, but he is always original. His creation of an ancient classical world- which passed in his time for a sort of archaeological study- was an extraordinary piece of romantic invention; it is so convincing that it persists today as part of a picture we have constructed with an accuracy that contradicts Mantegna’s vision. Obsessed by what he thought was the sculpture of antiquity, Mantegna himself probably considered his re-creations as a kind of archaeology, and in fact he was as close to being a scholar of the antique as was possible in his time.

Mantegna. Triumph of Ceasar. Jonathan Jones:The power of Mantegna's Triumphs is in what the painter does not show. Caesar returns to Rome bringing trophies, captives, standards. On one level this is a reconstruction of a Roman custom, the formal triumphal procession. Yet there's a melancholy air to these ceremonies. The soldiers do not gloat. One bearing an empty suit of armour on a pole looks at the ground meditatively, while another - who stands under a sky blackened by a forest of cuirasses, leg armour and helmets - stops and stares sadly into space. The unseen subject of Mantegna's painting is war; the looted statues, vases, treasure, slaves, were all obtained by slaughter. Mantegna does not let us forget the reality behind the victory. Even Caesar seems to know it.

He was a collector and apparently to some extent a dealer in classical fragments, but his century knew classical sculpture only in bits and pieces, most of them miserably debased in style. Greek sculpture was only a legend; although the Parthenon was not yet a ruin, and its sculpture was nearly intact on its pediments, it was unknown in the West. The Roman sculpture that now lines the halls of our museums had only begun to be discovered.

To realize the originality of Mantegna’s classical invention, we must remember that the predominantly classical architectural aspect of Italian cities that we now take for granted was not their aspect in Mantegna’s time. Instead of cities filled with the adapted classical elements of baroque architecture and the later rejuvenated, or embalmed, neo-classic structures, Mantegna first knew cities where the architectural flavor remained medieval. During his lifetime the classical transformation was taking place, but it took place as modernism, and Mantegna’s art contributed to the character it assumed.

Jones:Caesar is a stony-faced figure high on his chariot, his features modelled on Roman busts and coins, his body stiff as sculpture, while the people around him, children, soldiers, are more alive. Reading the series of paintings from left to right, this is the last. To reach Caesar at the rear of his triumphal procession is anticlimactic: is all this gold and tribute, this shaking of the world, for the fame of this one little man?

From fragments, from forgeries, from literary references, probably from collections of drawings that artists passed around among themselves as sorts of pattern books, and from the wonderfully evocative but decayed and half-buried architectural stage-set of the ruins of ancient Rome itself, Mantegna distilled his own ancient world- a world of wonderful completeness and of an austere purity. In this curious way he became one of the mightiest Romans of them all.

Through the legerdemain of his immaculate craftsmanship as a painter he also became, in effect, one of the most inventive of early Renaissance architects and one of the most decorative sculptors. The architectural settings that serve as backgrounds for the martyrdoms in the Ermtani frescoes may be buildings that were never planned to be built, but they would have been possible to build and are some of the most impressive architectural designs of their time on the classical model. In the background of the Louvre’s “Saint Sebastien”, Mantegna pictures a group of ruined buildings that give the event, nominally, a setting in the ancient world, but they are actually brilliant Renaissance designs first created and then shattered, a tour de force combining the vigorous genius of a Renaissance arch

t with the romantic nostalgia that accompanied the rebirth of classicism from the start.

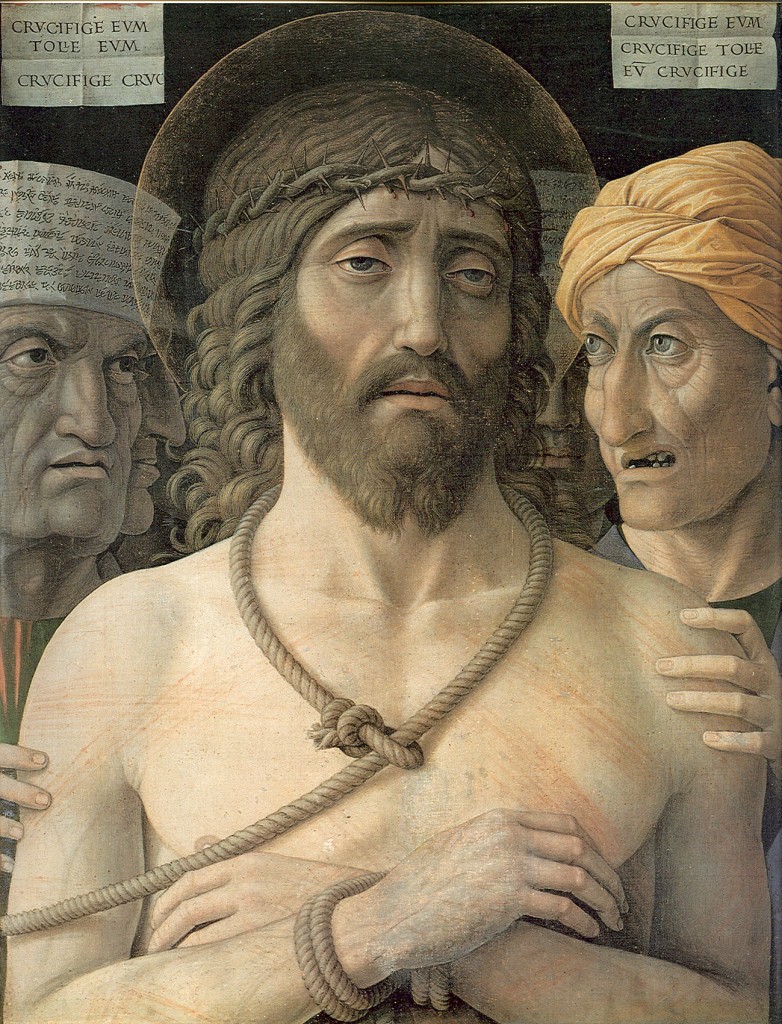

Kimmelman:His works are deeply cerebral and tough as nails in their hard-edged exactitude, and these qualities diminished him in the eyes of influential modern critics like John Ruskin and Bernard Berenson, who accused him of painting people "as if they were made of colored marble rather than flesh and blood." Berenson wasn't entirely wrong, but the show demonstrates that Mantegna could also be a profoundly affecting artist, as in his "Ecce Homo," where the gnarled features of the accusers serve to make more intense Christ's ethereal beauty. His "Virgin and Child," from the Gemalde galerie in Berlin, with its swaddled, sleeping baby tucked under the chin of His pensive mother, is no less touching an image of intimate emotion. And in "The Man of Sorrows With Two Angels," Mantegna's depiction of land and sky can even bring to mind the Romantic vistas of Caspar David Friedrich.

As a sculptor-architect working in paint, Mantegna created, in the staggeringly illusionist ceiling of the Camera degli Sposi, some of his century’s most beautiful bas-reliefs in an architectural framework. He seems to have taken delight in putting himself in the position of sculptor forced to work in acutely limited depth, and of a painter forced to create his stone with his brush. The resultant hybrids, including such drawings as “Judith” and most directly the frieze of the “Triumph of Caesar” , combine the beauties of both parents in a new harmony.

The “Triumph of Ceasar” , perhaps inspired by the reliefs of the Arch of Titus, makes the most direct kid of reference to the classical past and expresses the spirit of military theatricality so often reflected in Mantegna’s idea of the ancient world. There is no ambiguity in either the intention or the result- in contrast to Mantegna’s two most puzzling paintings where, instead of re-creating a spectacle as it could have existed, he enters the field of lyrical allegory as a favor to a lady, Isabella d’Este. …

Mantegna. Circumcision of Christ. ( circa. 1460).Leo Steinberg:A third constant in Patristic writings is the Circumcision of Christ conceived as continuous with his work of redemption. Since the debt incurred by the sin of Adam cannot be met by Adam's insolvent progeny and since Christ's blood pays the ransom his Circumcision becomes, as it were, a first installment, a down payment on behalf of mankind. It is because Christ was circumcised that the Christian no longer needs circumcision. In the words of St. Ambrose: "Since the price has been paid for all after Christ . . . suffered, there is no longer need for the blood of each individual to be shed by circumcision."

“Alberti’s conception of the pictorial image as a visual analogue to an actual scene provided the foundation for his equation of painting with historia. If painting was to be historia, it had to function simultaneously on at least two level; it had to present a convincing depiction of the world and it had to convey the higher meanings of the scene it presented. Prior to Alberti, writers attributed the multilevel significance of pictorial historia to the literary subject of the painting. Accordingly, the significative value of painting depended upon its being an accurate illustration of a text, not a representation of or a pictorial analogue for the visual world. If painters turned to the world around them, it was only to see beyond it.” [Greenstein, Mantegna and Painting as Historical Narrative]

Mantegna realized that the pictorial conventions developed by medieval artists to bring out the higher significance of Christ’s circumcision were not compatible with the representational fidelity of pictorial “historia” . Yet to have rejected traditional iconography would also have violated the historical sense of the painting by wresting the depicted event from the narrative context that conveyed the significance of Jewish rite to the Christian audience. This incongruity between the symbolic means and the narrative content of painting led Mantegna to consider questions about the Circumcision that had held little importance for theologians. As a result of his painterly interest in “historia” , Mantegna reached an understanding of the Circumcision of Christ that had no precedent in religious art or theological literature.

ADDENDUM:

(Leo Steinberg): There is a fourth point. By conceiving Christ’s Circumcision as a type of the Passion, the Fathers made it a volitional act. Never did it occur to a Christian writer (or painter) to think of that operation as imposed on an unwitting child. Christ’s submission to circumcision was understood as a voluntary gift of his blood, prefiguring and initiating the sacrifice of the Passion.

And one final point. Patristic literature associates the timing of the Circumcision on the eighth day with Resurrection. Here the argument rests on the kind of mystical numerology we no longer take seriously, but it did formerly engage some great minds. The reasoning runs somewhat as follows. Seven is the number of completion and fullness, for the world was created in seven days, and is due to pass through seven ages. But if seven is perfect, then seven-plus-one is pluperfect. Eight, therefore, stands for renewal, regeneration — whence the architectural tradition of eight-sided baptistries. And Christ rose from the dead on the day superseding the Sabbath, on the eighth day just as the world’s seven ages will be followed in the eighth age by the General Resurrection.

These notions attach themselves almost from the beginning to all theological meditation on Christ’s Circumcision. From St. Justin Martyr in the 2nd century to St. Thomas Aquinas, it is the sense of the mystery that the Circumcision on the eighth day prefigures Christ’s Resurrection, and thereby, implicitly, the resurrection of all. At the close of the Patristic era, the Venerable Bede (673-735) composed a classic homily “On the Feast Day of the Lord’s Circumcision.” His premise is, of course, solidly Augustinian. “You ought to know,” he writes, “that circumcision under the law wrought the same healing against the wound of original sin as does baptism in this time of revealed grace, except that under circumcision they were not able to enter the gate of the heavenly kingdom. . . .’, But Bede proceeds to draw an important conclusion. So long as circumcision was chiefly a token of initiation into Abraham’s covenant, Christ had need of it to qualify as a true son of Abraham. (Hence the lunette decoration above Mantegna’s scene of the Circumcision),But insofar as circumcision cancels Original Sin, from which Christ is exempt, he needed it not.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS