The most devoted lovers of Florentine art complain that as a stylist Mantegna lacks the breath and freedom and, as an expressive artist, the human warmth that the Tuscans offer. They cannot see that Mantegna’s rejection of movement and fluidity on one hand, and of softened, sweetened, and gentled forms on the other, was a rejection necessary to the almost frantic discipline that accounts for the intensity of the emotion he expresses. They find him cold.

Minerva Expelling the Vices From the Grove of Virtue.A puzzling work:Pallas Expelling the Vices was the second mythological garden painting Mantegna created for Isabella d’Este (Paris, Louvre, 1500-02, Figure 3). Isabella described the idea for it as “a battle of Chastity and Lasciviousness, that is Pallas and Diana combating vigorously against Venus and Cupid.” The goddess, Diana, however, is not pictured in the painting. Here we have two virgins, Athena and Daphne, driving out Lust and the Vices from the garden. Three of the Cardinal Virtues, Temperance, Justice, and Fortitude, having been driven out previously by the depravities which had been occupying the place, return to the garden in an oval cloud formation. The fourth Virtue, Prudence, is walled up inside the stone structure on the far right of the painting, and only a white fluttering banner reflects her cry for help." End Quote from "Gardens and Grottoes in Later Works by Mantegna" by Carola Naumer

Yet in Mantegna, emotion is not so much held in check as it is distilled to an essence so pure that it is too strong for most palettes. He is in many ways the most abstract, and hence the most modern, of all early Italian Renaissance painters. His special uses of perspective as an expressive device exemplify this fact.

Perspective is defined in the artist’s dictionary as “the art of picturing objects or a scene in such a way as to show them as they appear to the eye with reference to relative distance and depth.” True enough, but the fascination of perspective is that it is based on contradiction: it is a process of systematic distortion that, paradoxically, is a means toward the realistic representation of the world. Lines that are parallel are in fact inclined toward one another in perspective drawing; they converge. Large objects are made small, and small objects made large to express their distance from the eye. A disc becomes an oval to show that it is turned away from the observer. Squares become trapezoids. All objects are warped into false shapes in order to create the illusion of their true ones.

Francesca Gonzage commissioned he Madonna of Victory for a new chapel in Mantua to celebrate his defeat of the French at Fornovo in 1495. On the first anniversary of the battle the painting was carried in procession and installed in the chapel. But the final victory went to the French after all. In 1797 the painting was brought to Paris by the French army and it has remained there, in the Louvre, ever since.

Since the camera does all this automatically, and since artists have been doing this for five hundred years, we forget the excitement of the fifteenth century when the rules for this distortion were being discovered. The creation of illusions of space, volume, and distance was cross between a magician’s trick and a scientific diagram, and it carried an impact that is so lessened for us today, through familiarity, that we must make an effort to imagine the preoccupation, to the point of obsession, of early Renaissance artists with this new device.

Perspective was a sudden enlargement of the artist’s field of expression; in virtually a literal way it opened new vistas. Before the perfection of perspective drawing, it was as if painters had had to stage their dramas on the apron- the part of the stage in front of the curtain- or at best in an extremely shallow space. Perspective raised the curtain and gave them not only all the stage but all the world behind it, to the deepest horizons. The rules for perspective could even be used in the fabrication of convincing vistas, heavenly or hellish, that the eye had never seen. The resultant art was not necessarily “better” , since great art again and again is produced under limitations, but the means became more flexible and the potential range of expression wider, for any artist capable of making the most of them.

Some writers say the depiction of Jerusalem matches the description the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus made. Detail by detail, The Agony in the garden ( San Zeno ) may seem to offer little that is not found in the work of mantegna's contemporaries: the disciples asleep, the file of centurions, the imagined Jerusalem on the rocky hill, the blasted tree. But what makes it unmistakenly Mantegna's is its strangely compelling amalgam of the sinister and the mysterious.

Mantegna made the most of perspective by conceiving his dramas in a full three dimensions- whether the space he was creating was limited to the bowered niche that embraces the figures of the “Madonna of Victory” , or was extended as in the the craggy and stony world of “The Agony in the Garden. But these uses are usual, if expert. What distinguished Mantegna in his use of perspective is that, more than any other artist of his time, he capitalized on it not as a form of realism, but as a form of distortion that could intensify the emotional content of a painting.

In his earliest major work, the frescoes of the Eremitani Church in Padua, Mantegna seems to have set out, with a prodigy’s bravado, to demonstrate his mastery of perspective in a series of representations of saintly martyrdoms. By perspective he opened the wall in a series of cubicles filled with monumental structures and crowds of figures, but instead of conceiving each cubicle as if seen from a conventional level, he sharpened the perspective in the “cubicles” to make the scene take place well above the observer’s position on the floor. The effect of this device was not so much one of illusion as magical intensification of the actors; and in a subject of potential violence, the only violence was supplied by a perspective that was in itself violent in the angles of its lines and its sudden juxtaposition of large and small figures. What might have been only an ordinary representation

a “tableau vivant” becomes extraordinary in its air of threat and irreality.

The foreshortening in Dead Christ, Mantegna's most audacious painting, is so extreme that it risks being ludicrous- and it would be, if it had not produced an image so arresting that it forces a new consciousness of a standard subject. There is an earlier version of this picture without the two mourners, Saint John and the Virgin, who have been awkwardly crowded in at the left as the painting's one concession to convention. But even their intrusion cannot much reduce the atmosphere of majestic and tragic isolation that shocks us with its proclamation of our own mortality.

To what extent this effect was precalculated is anybody’s problem for discussion. But the principle revealed here was later employed by Mantegna in one of the most arresting paintings of his century, “Dead Christ” . It is a picture impossible to pass by, a picture that jolts you with its first impression of violence. Yet by any objective analysis it is much more restrained than many paintings that, while they make a point of agony, carry none of the emotional shock of this one- a shock that Mantegna produces through the distortions involved in acute foreshortening. The height of the figure is so compressed that it is almost exactly equal to its width.

Many observers and some critics reject the picture in its Christian context; they admit its power as a representation of a corpse but find it only a disturbing reminder of the body’s mortality impossible to associate with the idea of resurrection. This is a matter of individual response; the picture has always seemed as reverent as it is reserved. It is also a superb technical achievement in which Mantegna as a great craftsman comes out triumphant over the hazards presented by the daring concept of Mantegna the artist.

"Mantegna's principal works in Padua were religious. His first great success was a series of frescoes on the lives of St. James and St. Christopher in the Ovetari Chapel of the Church of the Eremitani (1456; badly damaged in World War II). In 1459 Mantegna went to Mantua to become court painter to the ruling Gonzaga family and accordingly turned from religious to secular and allegorical subjects. His masterpiece was a series of frescoes (1465-74) for the Camera degli Sposi (“bridal chamber”) of the Palazzo Ducale. In these works, he carried the art of illusionistic perspective to new limits. His figures depicting the court were not simply applied to the wall like flat portraits but appeared to be taking part in realistic scenes, as if the walls had disappeared. The illusion is carried over onto the ceiling, which appears to be open to the sky, with servants, a peacock, and cherubs leaning over a railing. This was the prototype of illusionistic ceiling painting and was to become an important element of baroque and rococo art."

The depiction of a human being lying down with the soles of his feet facing us could easily be ludicrous; it is, in fact, a standard gag shot with amateur photographers. But Mantegna proportioned the resultant distortion not by the laws of optics but by a combination of observation and discretion, creating an image that forces us into a new consciousness of the subject. It is as if we had never before seen a representation of the dead Christ. The picture is powerful, moving and true, where it might have been only eccentric.

ADDENDUM:

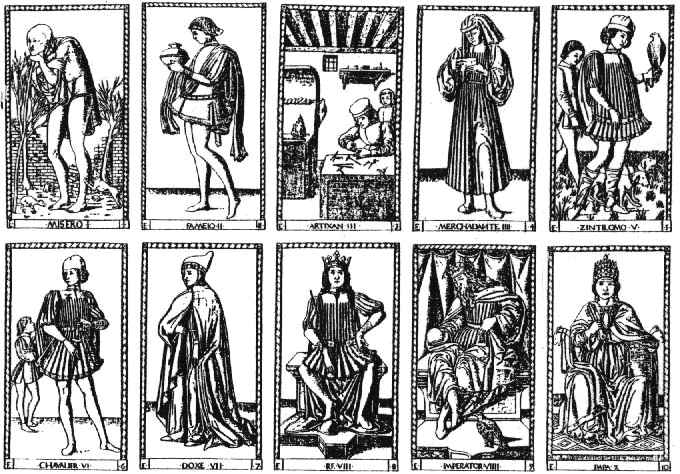

Adam McLean: This reconstruction of hermetic and neoplatonic esotericism is reflected in such ideas as the Muses, the Liberal Arts, the Cardinal Virtues, and the Heavenly Spheres, and it is my view that the Tarocchi of Mantegna should be seen as an 'emblem book' of this hermetic current. The fact that its designs show parallels with the later tarot decks should therefore be of the greatest interest both to students of tarot and of Hermeticism. There is in this sequence both a reflection of the social conditions of humankind and also the stages of an inner development, from the lowly 'beggar' state of soul, to the fully spiritualised 'Pope' facet of the soul. Interestingly, these fit well onto the tree of life diagram corresponding to the sephiroth quite tightly, but can also equally well be tied symbolically to the Pythagorean 'Tetractys' or pyramid.

Mantegna worked for Isabella d’Este of Ferrara who was closely connected with the earliest references to the tarot (trionfi) cards, and even painted two “trionfi” pictures for her: Parnas or the triumph of love and The triumph of virtue. It is now generally accepted that both early tarot decks and various other “triumph” themes in the early Renaissance Italian art have their common source in triumphal parades of the period and in Petrarch’s influencial poem I trionphi. The basic idea of these was a sequence of images or personifications, each of which “triumphed” over the preceding one, and the same scheme can be observed in the Mantegna series. Another hypothesis connects the tarot images with the hermetic art of memory but it has been overlooked that both of these theories converge in the person of Petrarch who was regarded as the father of that art. It seems, therefore, that it was Petrarch’s idea to use the images of triumphal parade as vehicles for the art of memory images, while some later artist used the same idea for visual images of the earliest trionfi cards.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

The two figures crammed into the upper left corner of ‘Dead Christ’ almost reads like a hollywood ending tacked onto an stark, minimal composition that may have been unacceptable to the public of that time. The brighter palette used for the mourners is certainly inconsistent with funereal lighting of the corpse and the farther figure’s hand looks unusually large.