Freud said of folk tales that they contain “the dreams of the human race.” One of these dreams is about the simple good prevailing over the subtle wicked. Most of the stories that the Grimm brothers collected are lay moral sermons.

This fact probably justifies the nightmare element that troubles so many teachers, parents and educational publishers. Some terrible things can happen in the tales, but there is a severe moral logic in them. Evil itself is not just vague malevolence but an actively destructive impulse that is pushed on to the ultimate enormity of cannibalism; neverthless, there is no gratuitous dwelling on violence and horror: the reports are abstract, the hacked bones and pools of drying blood are mere emblems that do not quite belong to the world of true sensuous experience.

Walter Benjamin:The storyteller does not try to convey dry, impersonal information; he sinks the story into his own life, in order to bring it out of him again. Story-telling itself is not a liberal art, but a craft. The great story is therefore a carefully crafted thing, the "precious product of a long chain of causes similar to one another". It takes time, a lot of time, to create such a story; and this is why story-telling is dying out. "All these products of sustained, sacrificing effort are vanishing, and the time is past in which time did not matter. Modern man no longer works at what cannot be abbreviated."

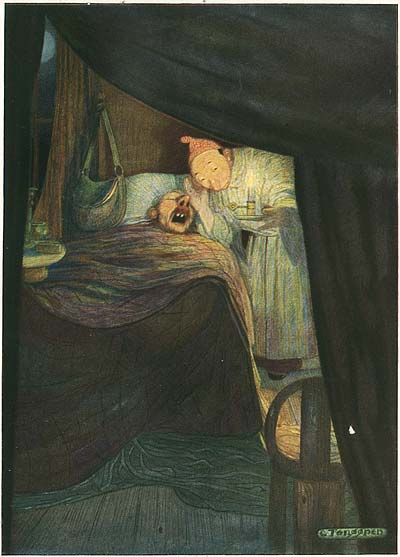

And sometimes the horrors are reversible, so that we cannot take them seriously. The maiden who goes to the evil house to find her sisters cut to pieces has only to set limb to limb, like the bits of a jigsaw puzzle, and the girls come back to life again. It is manifestly impossible for the wolf to swallow Red Riding Hood and her grandmother whole, so that they may be taken out of his belly- in shock but otherwise little the worse- by a sort of Caesarean operation. The evil is not quite the photographed iniquities of the Nazis: it is a potential realized in symbols, and it is often enclosed in ritual. But it is frightening enough, recounted by a guttering candle or in the owl haunted dark. Ought children to be protected from it?

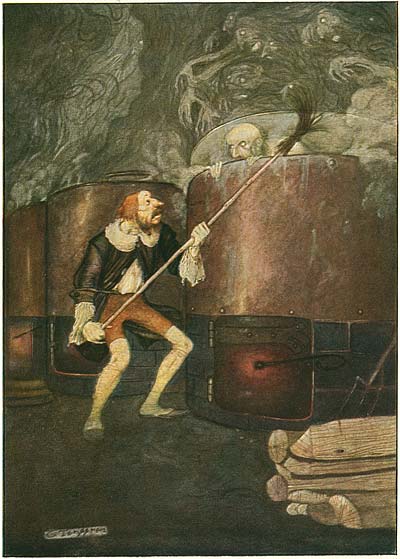

Lisa Falzon art. Joseph Campbell:By an ironic paradox of time, the playful symbolism of the folk tale--a product of the vacant hour--today seems to us more true, more powerful to survive, than the might and weight of myth. For, whereas the symbolic figures of mythology were regarded (by all except the most sophisticated of the metaphysicians) not as symbolic figures at all but as actual divinities to be invoked, placated, loved and feared, the personages of the tale were comparatively unsubstantial. They were cherished primarily for their fascination. Hence, when the acids of the modern spirit dissolved the kingdoms of the gods, the tales in their essence were hardly touched. The elves were less real than before; bu the tales, by the same token, the more alive. So that we may say that out of the whole symbol-building achievement of the past, what survives to us today (hardly altered in efficiency or in function) is the tale of wonder.

For a child, even without the Grimm brothers, there is no shortage of gruesome doors into the Gothic wings of one’s dream house. Children, and adults for that matter, will always find something to have nightmares about. A much more important question is this: are the Grimm tales corruptive, are they likely to whet daydreams of violence? Unlikely, they are far more likely to instill a profound sense of the moral order.

It is, for the most part, a pre-Christian moral order, with an inexorable apparatus of punishment. A man allows a cart to run over a dog. A sparrow, the dog’s friend, pursues retribution to the limit, pecking out the horse’s eyes, pecking the bungs out of the cartload of wine casks. Finally the man swallows the sparrow whole, but the bird flutters back into his mouth. “Wife,” says the man, giving her an axe, “kill the bird in my mouth for me.” The woman strikes, misses, hits her husband on the head, and kills him. The bird, its rhadamanthine duty done, flies away. Perhaps the punishment goes to far, but the lesson is bound to get home to a juvenile audience. Better the odd nightmare than a boyhood dedicated to cat-torturing and pulling wings off flies.

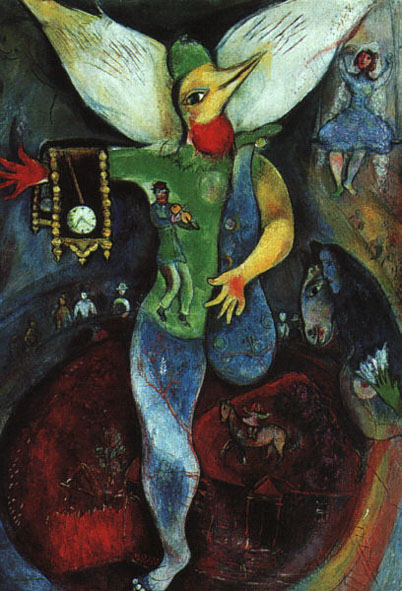

Campbell:And so we find that in those masterworks of the modern day which are of a visionary, rather than of a descriptive order, the forms long known from the nursery tale reappear, but now in adult maturity. While the Frazers and the Müllers were scratching their necks to invent some rational explanation for the irrational patterns of fairy lore, Wagner was composing his Ring of the Nibelung, Strindberg and Ibsen their symbolical plays, Nietzsche his Zarathustra, Melville his Moby Dick. Goethe had long completed the Faust, Spenser his Faerie Queene. To-day the novels of James Joyce, Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann, and many another, as well as the poems of every season, tell us that the gastric fires of human fantasy still are potent to digest raw experience and assimilate it to the creative genius of man. In these productions again, as in the story world of the past which they continue and in essence duplicate, the denotation of the symbols is human destiny: destiny recognized, for all its cannibal horrors, as a marvelous, wild, "monstrous, irrational and unnatural" wondertale to fill the void.

“I don’t care”: “Don’t -care was made to care,/Don’t- care was hung,/Don’t-care was put in a pot/And cooked till he was done

That, when you come to think of it, is grim enough. The rhyme has a ritual force about it, like a liturgical execration, and it plants a certain uneasiness. No child hearing or reading the sterner of the Grimm stories can remain wholly innocent any longer. He has been introduced, through delicious rites of terror, into the horrible but necessary world of experience.

Not all the stories are moral. Some of them seem to encapsulate ancient myths of spring and winter: Snow White is a vegetarian goddess like Persephone. And those tailor-dwarfs who get inside thimbles are surely Priapus in disguise. Some stories are just sophisticated nonsense- surrealism, if you like: “There were two cows which were mnowing a meadow, and I saw two gnats building a bridge, and twodoves tore a wolf to pieces; two children brought forth two kids, and two frogs threshed corn together. I s

wo mice consecrating a bishop, and two cats scratching out a bear’s tongue.”

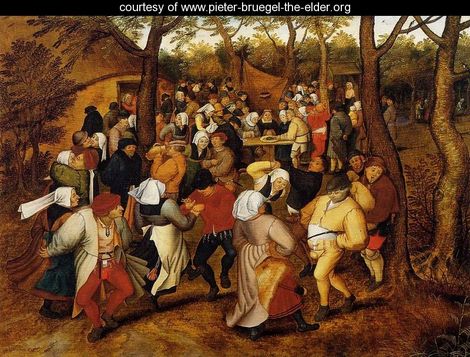

Pieter Brueghel. Benjamin:Erinnerung (remembrance) takes different forms in the story and the novel. In the story, it appears as Gedächtnis (memory). The cardinal point for the unaffected listener to a story is to assure himself of the possibility of reproducing it. Memory (Gedächtnis) is the epic faculty par excellence. Only by virtue of a comprehensive memory can epic writing absorb the course of events on the one hand and, with the passing of these, make its peace with the power of death on the other. In the novel, on the other hand, Erinnerung appears as Eingedenken (reminding?). The novel is about a particular character, event or situation; of which it 'reminds' us.

Others provide privy warnings for young and foolish wives- like the tale of Frederick and Catherine. Catherine, when she drops a cheese down the hill, send another cheese after it to bring it back. And another. And another. And sometimes we touch the fringes of true German sentimentality, as in the story of the poor peasant boy who goes to church and believes he is in heaven-“next Sunday, when the host came to him, he fell down and died, and was at the eternal wedding.”

But the stories are all very firm, confident, sure of themselves. Once started, they travel to the end of the shortest route, wasting no time on decorative fripperies, Jamesian qualifications, or depth psychology. “There was a man who had three sons, the youngest of whom was called Dummling, and was despised, mocked, and sneered at on every occasion.” We,re off and we stay till the finish. If anybody cavils at the improbable, grumbles about too much magic, laughs in the wrong place, he will be told to hold his tongue or receive a salutary slap.

"Pieter Bruegel the Elder, a Dutch painter and printmaker, was known for his landscapes and peasant scenes. Some call him “Peasant Bruegel” to distinguish him from other members of the Brueghel dynasty of painters. Within his landscapes Bruegel recounted folk stories, combining several elements of a story within a single painting. Many paintings have a cartoon character which may have concealed complex levels of aphorisms, satire and social commentary."

And an ancient crone is telling the story, toothless, parchment skinned, very vigorous, vibrant with authority. Having listened to her voice through eight hundred pages of re-reading Grimm, one can become restive at the slow-moving, tentative, groping, unsure techniques of the contemporary novel. “Once upon a time there was a boy who was brought up among goats, and he believed himself to be a goat.” That’s how Mr. Barth’s masterpiece ought to begin. And it could learn something about brevity from these old tales, told after work or on a holy day of obligation.

‘one upon a time there was a man called Rojack , and he hated his wife so much that he had to kill her.” That’s Norman Mailer’s “An American Dream” “There was once a man who was always writing letters to people, but he never sent any of these letters off.” We all know Saul Bellows’s Moses Herzog or the characters that inhabit Paul Auster. One of these days the Grimm brothers will be seen to have started something.

Brueghel. Walter Benjamin:The fairy-tales is the earliest step man has taken to free himself from the pressure of the mythical. The liberating magic which the fairy tale has at its disposal does not bring nature into play in a mythical way, but points to its complicity with liberated man. A mature man feels this complicity only occasionally, that is, when he is happy; but the child first meets it in fairy tales, and it makes him happy.

ADDENDUM:

Joseph Campbell: Through the vogues of literary history, the folk tale has survived. Told and retold, losing here a detail, gaining there a new hero, disintegrating gradually in outline, but re-created occasionally by some narrator of the folk, the little masterpiece transports into the living present a long inheritance of story-skill, coming down from the romancers of the Middle Ages, the strictly disciplined poets of the Celts, the professional story-men of Islam, and the exquisite, fertile, brilliant fabulists of Hindu and Buddhist India. This little mare that we are reading has the touch on it of Somadeva, Shahrazad, Taliesin and Boccaccio, as well as the accent of the story-wife of Niederzwehren. If ever there was an art on which the whole community of mankind has worked–seasoned with the philosophy of the codger on the wharf and singing with the music of the spheres–it is this of the ageless tale. The folk tale is the primer of the picture-language of the soul.

Campbell:The Grimm brothers regarded European folklore as the detritus of Old Germanic belief: the myths of ancient time had disintegrated, first into heroic legend and romance, last into these charming treasures of the nursery. But in 1859, the year of Wilhelm's death, a Sanskrit scholar, Theodor Benfey, demonstrated that a great portion of the lore of Europe had come, through Arabic, Hebrew and Latin translations, directly from India--and this as late as the thirteenth century A.D.

Walter Benjamin: Seen in this way, the storyteller joins the ranks of the teachers and sages. He has counsel – not for a few situations, as the proverb does, but for many, like the sage. For it is granted to him to reach back to a whole lifetime (a life, incidentally, that comprises not only his own experience but no little of the experience of others; what the storyteller knows from hearsay is added to his own). His gift is the ability to relate his life; his distinction, to be able to tell his entire life. The storyteller: he is the man who could let the wick of his life be consumed completely by the gentle flame of his story. This is the basis of the incomparable aura about the storyteller, in Leskov as in Hauff, in Poe as in Stevenson. The storyteller is the figure in which the righteous man encounters himself.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS