Now in Vienna there’s ten pretty women

There’s a shoulder where Death comes to cry

There’s a lobby with nine hundred windows

There’s a tree where the doves go to die

There’s a piece that was torn from the morning

And it hangs in the Gallery of Frost

Ay, Ay, Ay, Ay

Take this waltz, take this waltz

Take this waltz with the clamp on its jaw… ( Leonard Cohen, Take This Waltz )

The last waltz in Vienna. Danced to the music of Strauss, in that gay city of crystal and cake, it soon turned into a dance of death- its cadences marked by Hitler, Freud, and the guns of the First World War.

"Despite his established career on the big screen, Haneke frequently returned to work on television projects in the 1990s include this adaptation of Joseph Roth’s novel. In it, he explores the fate of a returning veteran in post-World War I Vienna who struggles (like many of Haneke’s protagonists) in an increasingly bureaucratic and technocratic world."

…The music and laughter have gone, the crystal sphere lies in a thousand pieces, and that vanished and forgotten city has no more substance now than the royal capital of some improbably fairyland. It survives only in the imagination: a mocking symbol of “die gut alte Zeit” , the old impossible time when splendor was not an embarrassment and elegance was more than a word.

…Oh I want you, I want you, I want you

On a chair with a dead magazine

In the cave at the tip of the lily

In some hallways where love’s never been

On a bed where the moon has been sweating

In a cry filled with footsteps and sand

Ay, Ay, Ay, Ay

Take this waltz, take this waltz

Take its broken waist in your hand…

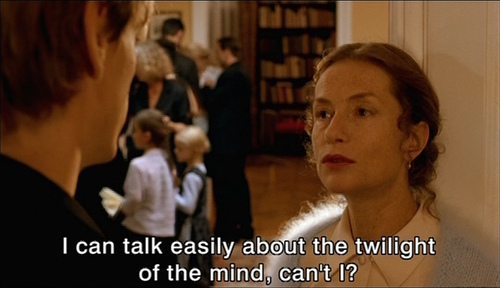

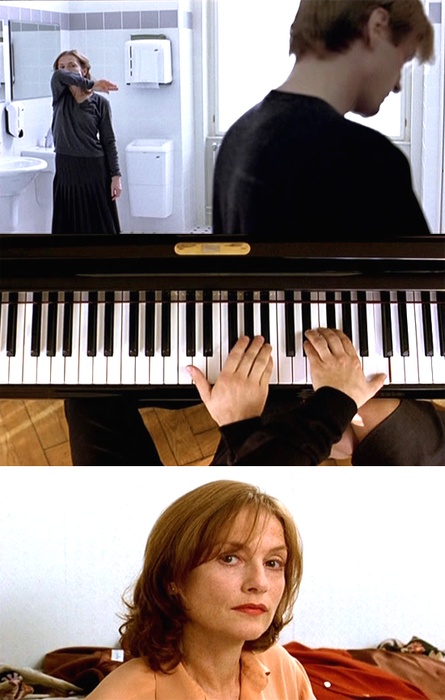

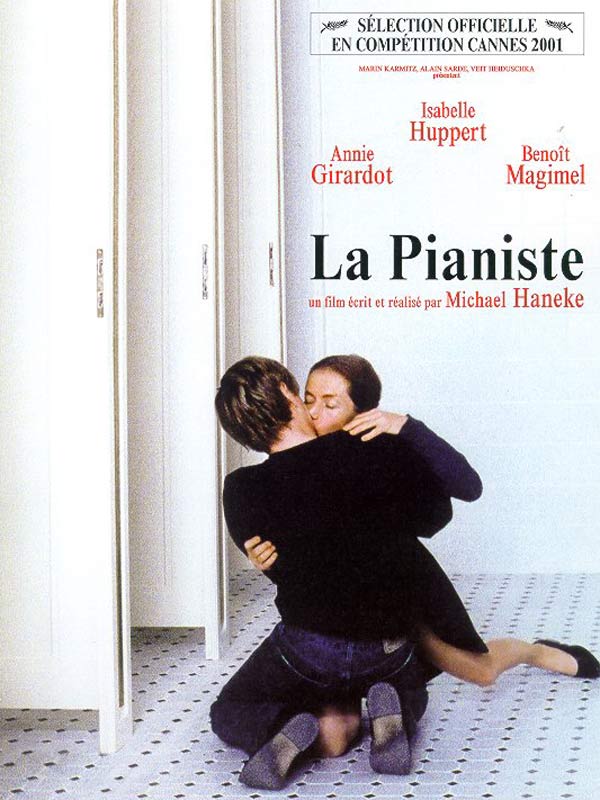

Haneke. The Piano Teacher. John Champagne: There are a number of different ways the film reinforces both this sense of Erika’s mother as "phallic," and the lack of distance between the two women. Erica’s father is physically absent from the film entirely. A musician who had himself gone mad, he is long dead when the film begins. His connection to Erika is reinforced by the fact that both of them are particularly fond of the music of Schubert and Schumann. The choice of these composers is not accidental, Schubert — rumored to have had homosexual relationships — having died of syphilis, and Schumann having himself gone mad. Both composers thus reference in different ways a relationship among great works of art, insanity, and gender identity — Schumann having been in his later years dependent upon his wife Clara, herself a composer of some talent whose gifts were overshadowed by her husband’s.

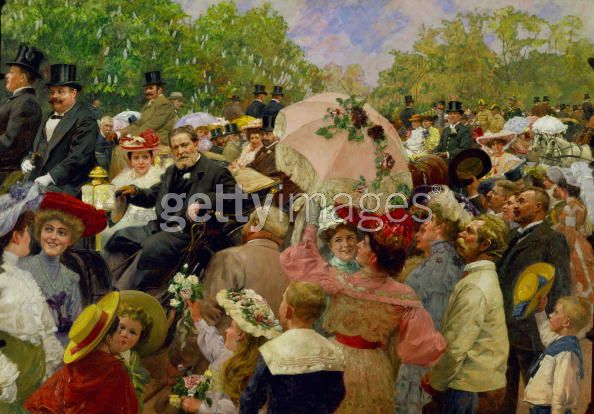

Vienna in the twilight of the hapsburg empire was that enchanted city, and one of the lovely capital of the “ancien regime” . By the jubilee year of 1898, which marked Franz Josef’s half century on the throne, it was firmly established as a charming and outrageous anachronism- a city of facade and waltzes and blue rivers. It was one of the last romantic outposts in a civilization moving with speed into the harshness of the twentieth century. The air of illusion that hovered over Vienna at the turn of the century was perhaps inevitable. The city itself was too beautiful to be entirely true. …

The persistent inability to take anything very seriously has long been a characteristic of all classes of Viennese society. As early as 1843 an Austrian writer could say: “The people of Vienna seem to any serious observer to be reveling in an everlasting state of intoxication. Eat, drink and be merry are the three cardinal virtues and pleasures of the Viennese. It is always Sunday, always Carnival time for them. There is music everywhere. The innumerable inns are full of roisterers day and night. Everywhere there are droves of fops and fashionable dolls.”

The Piano Teacher. Champagne: This coldness, bordering at times on the cruel, is contrasted sharply in the film by her brilliant and moving piano playing, suggesting the complexity of her relationship to gender. For to be a professional female pianist means to compete in what is still chiefly a man’s domain, a domain that is itself sometimes contradictorily constructed as "feminine" if not" effeminate." Again, Erika’s fondness for Schubert and Schumann is significant, as both men were "sickly" — an attribute heterosexist culture sometimes assigns to effeminate or homosexual men.

…This waltz, this waltz, this waltz, this waltz

With its very own breath of brandy and Death

Dragging its tail in the sea

There’s a concert hall in Vienna

Where your mouth had a thousand reviews

There’s a bar where the boys have stopped talking

They’ve been sentenced to death by the blues

Ah, but who is it climbs to your picture

With a garland of freshly cut tears?

Ay, Ay, Ay, Ay

T

Take this waltz it’s been dying for years…

The “fin-de-siecle” carnival spilled over into the twentieth century. Great emphasis was put on social precedence, and elaborate masques were stage continually. The surface of life was enchanting; the days and the nights sparkled with handsome uniforms and military bands and operas and court balls.

Haneke. The Piano Teacher. Champagne:Also of pertinence to the film’s feminism is Walter’s ability to become a sadist. Gilles Deleuze has argued, contra Freud, that masochism and sadism are not "complementary" perversions, but rather constitute two different perversions with different aims, aesthetics, and ends. According to Deleuze, one characteristic that differentiates the masochistic scene from the sadistic scene is the fact that the masochist must seduce the sexual partner into meting out punishment, while in the sadistic scenario, the sadist is pursuing his own desire to inflict pain. While the film makes clear that Walter is following Erika’s directions, the actual scene in which the masochism is played out suggests that it is not masochism, but sadism, for it is Walter’s desire that has driven him to her in the middle of the night.

There was the magnificent Vienna State Opera. The building itself had been completed in 1869, and Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” had been chosen for the gala opening. Diamond gleamed and silks rustled in the long loggia with its statues of the nine Muses, in the vestibule with its gold leaf and ivory gesso, and on the soaring Grand Staircase with its crimson carpet. Under Gustav Mahler, who directed the opera until 1907, one glorious performance followed another: Betthoven’s “Fidelio”, Charpentier’s “Louise” , Puccini’s “la Boheme” and “Madame Butterfly”. There were less demanding entertainments as well, such as the charming and frivolous society comedies by Arthur Schnitzler, such as “Anatol” .

…There’s an attic where children are playing

Where I’ve got to lie down with you soon

In a dream of Hungarian lanterns

In the mist of some sweet afternoon

And I’ll see what you’ve chained to your sorrow

All your sheep and your lilies of snow

Ay, Ay, Ay, Ay

Take this waltz, take this waltz

With its “I’ll never forget you, you know!” …

Maria van Dijk:... uses Vienna as its backdrop. Amongst its other high-cultural connections, Vienna is closely associated with Freud as the birthplace of psychoanalysis. Although the city does not figure prominently in this film, the location is highly ironic as we are given no insight into the central character’s disturbed mind. Despite her grotesque relationship with her mother and increasingly distressing, violent behaviour, Haneke offers us no explanations. His directorial tone is economic and neutral. He rejects the obvious potential for sensationalist sex and horror and neither criticizes nor condones Erika’s actions. The result of this reserve and objectivity is, surprisingly, the most lacerating and troubling film of 2001.

The great good times and little indulgences never seemed to end. In those amusing days of imperial Vienna, under the light of the crystal chandeliers and with the sound of violins the old song was a compelling one: “Vienna, Vienna, you alone/ Shall always remain/ The city of my dreams.” At the turn of the century few people in Vienna sensed that the night was coming at last and that the whole gorgeous fabric would soon dissolve, leaving hardly a trace behind.

Oddly, the city was at its brightest in this autumn of decay.There was Holy Thursday, which began at five in the morning when twenty-four imperial carriages with liveried servants and a mounted escort drove out of the courtyard of the Hofburg. The coachmen wore huge three-cornered hats with silver braid, and yellow and black coats with white fur. The carriages took an unaccustomed turn toward the poorest quarter of Vienna. There twelve old man and twelve old women waited to be taken back to the palace for the medieval ceremony of foot washing and a banquet they would be too frightened to eat.

Karl Lueger, Vienna's mayor in 1904, is depicted in a park scene surrounded by gay admirers. The reality was grimmer: Lueger forged his political strength by frank anti-Semitic appeals to Vienna's lower classes.

…And I’ll dance with you in Vienna

I’ll be wearing a river’s disguise

The hyacinth wild on my shoulder,

My mouth on the dew of your thighs

And I’ll bury my soul in a scrapbook,

With the photographs there, and the moss

And I’ll yield to the flood of your beauty

My cheap violin and my cross

And you’ll carry me down on your dancing

To the pools that you lift on your wrist

Oh my love, Oh my love

Take this waltz, take this waltz

It’s yours now. It’s all that there is

The emperor and the archdukes and the princesses would kneel and pass a wet towel over the bare feet of these old people. Then the emperor would wash his hands in a golden basin held by two pages, as a signal that the ceremony was over. After the banquet he would hang a sack containing thirty pieces of silver around the necks of each of the old men and women. Finally, they would be taken back to their hovels, carrying baskets of food and bottles of wine and flowers from the imperial conservatories- having seen fairyland once before the end of their weary lives.

As an impoverished artist, Hitler spent five years in the flophouses of Vienna. This sketch, at sixteen, was made by an Austrian classmate.

These ceremonies were played to old familiar music that no longer had any meaning. The twentieth century was beginning, and Europe was entering a new dispensation. Under the Hapsburg’s however, the “ancien regime” was preserved in a way that was apparent in no other country, with the possible exception of Russia. The Few stood in opposition to the Many, using taste and elegance and an over-refinement of manner as weapons to hold back the future.

The bread and circuses of reaction, nevertheless, were splendid enough, and many an intelligent Viennese was fooled by them. Even the writer Hermann Bahr, who led the rebellios Young Vienna movement of the 1890’s that included Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Arthur Schnitzler, admitted that he had failed to recognize the truth. “I mistook the dying afterglow,” he said, “for the first flush of dawn.”

"La Ronde, originally titled Der Reigen (a round-dance or roundelay, published as Hands Around in English) was first "handed-around" in a private edition in 1900, Vienna. The play, which follows the sexual affairs of 10 couples, one each appearing in the next scene, was recognized as too outspoken even by its author. Schnitzler was, nonetheless, shocked that when the play was produced in 1903, it caused a major scandal, anti-Semitic riots, and the banning of the play. It was not revived again in that city until 1920."

It was an easy mistake to have made, for the afterglow was appealing and enormously bright. As long as you saw only the Hungarian Life Guard and the ladies of fashion, and listened to the clatter of horses’ hoofs in the spring rain, and heard the waltzes and the polkas and the gypsy violins. As long as you did not know that homeless men were sleeping in the sewers. As long as you were not familiar with the Archduchess Marie Valerie’s favorite charity, the Vienna Association for Warming Rooms and Welfare. In 1901 the association provided 368,000 men, 228,000 women, and 583,000 children – all citizens of the enchanted city- with a place to warm themselves at night and a piece of bread and a serving of soup.

---Schnitzler's Traumnovelle ("Dream Novella") was first published in 1926. It has long been available in English translation with the title Dream Story or Dream Novel. Schnitzler was a contemporary and friend of fellow Viennese Sigmund Freud, but the two had very different theories and approaches to human sexuality. Traumnovelle reflects Schnitzler's then shocking views on the subject in the 1920s. Director Stanley Kubrick, who died on March 7, 1999, only months before the release of "Eyes Wide Shut," had wanted to make a picture based on Schnitzler's story ever since first reading it around 1968. (Kubrick was born in New York City just two years after the first appearance of Traumnovelle.) Kubrick bought the rights to "Dream Story" through an intermediary, but did nothing with it for over 20 years. When the Austrian novella finally became a screenplay, the original fin de siècle Viennese characters of Fridolin and Albertine turned into Bill (William) and Alice in turn-of-the-century New York. The married couple's "Doppelexistenz" and their struggle to distinguish between dreams and reality are the theme of the book and the film.---

Near the fashionable shopping streets of Graben and Kohlmarket and the tall baroque palaces of the Inner City were slums and tenements as dark and monstrous as any that could have been seen in the worst days of Liverpool and London and paris and St. Petersburg. The air was full of the odor of mildew and paprika and the fumes of squalid goulash kitchens. The incongruities of imperial Vienna were apparent to many, but mostly to the poor. A young Adolf Hitler spent several miserable years there before the First World War, remembering later that hunger had been his only companion and that the Ringstrasse had seemed “like a fairy tale out of The Arabian Nights.”

In 1907 Hitler left Linz and came to Vienna to present a portfolio of drawings for admission to the Academy of Fine Arts. He was turned down, and so began a shadow existence in the city’s slums, where at first he lived in a tiny room on the second floor of a dingy house near the Westbahnhof. By 1908 he had gone to a home for men on the Meldemannstrasse, where each man had an iron bed, four meters of floor space, and twelve meters of “breathing space” . At this period Hitler could have been seen dressed in a ragged coat, with dirty gray trousers and disintegrating shoes and sunken cheeks, one of that army of defeated men who lived in the sewers and parks and flophouses of imperial Vienna. “Even now I shudder,” he wrote in “Mein Kampf” , “when I think of those pitiful dens, the shelters and lodging houses, those sinister pictures of dirt and repugnant filth, and worse still.”

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS