Although scholars agreed that Vienna was not the only place where Modernism achieved sweeping successes, it was still common practice to regard “Vienna as the focal point of European Modernism” . Scholars consider that European Modernism reached its purest and most concentrated expression in Vienna at the turn of the century. The foundations of 20th century thought were not created in Vienna alone, but what would this century have been without Freud’s psychoanalysis, without Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve-tone music, without Arthur Schnitzler’s “soul-scapes” or without Gustav Mahler’s music and his interpretation of the music of his contemporaries.Something was in the air, or perhaps it was in the water, and was creating a series of contradictory flash points that that seems unresolvable……

Modernism is both linked to the glory of Klimt’s paintings and superlative achievements in the field of science, and is also overshadowed by aberrant political phenomena such as virulent anti-Semitism, by political tension and disputes, particularly between the various nationalities. The excellence of artistic and scientific feats was able to eclipse these problems, but not to resolve them. The turn of the century was a period of transition, ambivalent in many ways, in which all the seeds for the disasters of the 20th century were sown.

“Already at the beginning of the century people had an inkling of the existence of a certain highest centre of power behind the scenes. On several occasions Rudolf Steiner speaks of the Austrian writer Hermann Bahr and his novel Himmelfahrt (Ascension). The novel tells of an Englishman who travels the entire world in search of the key to an understanding of human destinies. Finally he discovers certain invisible threads woven as a unified power around the whole world. The Englishman has the wish at all costs to penetrate to the inner circle of this power. It says in the novel, that he was not averse to holding the Jews in high esteem and occasionally voiced in all seriousness his suspicion that maybe in the innermost circle of this hidden world-web Rabbis and Monsignori sit together in perfect concord. Rudolf Steiner adds to this quote from the novel: And you can be quite sure … Hermann Bahr got to know this Englishman! All this is from life …”

The turn of the century also generated the vocabulary that provided the slogans for the atrocities of the 20th century and can thus be held responsible for having supplied the leitmotifs. Ideas that gave rise to the evil deeds in the middle of the 20th century were born as terms and concepts during the fin-de-siècle. The term “degenerate“, for instance, was coined by Max Nordau (1849–1923), the confirmed Zionist and the Paris correspondent of the Neue Freie Presse in Paris, to describe the elements he considered negative in his time. We all know the way in which this term was used later on.

…The early twentieth century in Vienna. They were still dancing to the music of Strauss in a city known for its gaiety, crystal and cake. But it soon turned into shattered glass and a dance of death; a syncopated rhythm whose cadences were marked by Hitler, Freud and the war dance of the First World War. re-humanized suffering by showing it to be inseparable from the vicissitudes of individuality, confirming its tragedy in an existentially indifferent society. The pathetic figures that the Parisian”peintres maudits” and the Viennese romanticists portrayed were the soft underside of the hard instrumental society celebrated by the idealized geometry of the Constructivist art that developed parallel to it.

It was also during the era of Vienna Modernism that crisis was accepted as an element of development, as a potential way of life. More recently, scholars have ceased to believe in continuous progress, in the final achievement of harmonious uniformity in some far-away future. They have begun to consider the conscious acceptance and appreciation of diversity, contradiction and heterogeneity

as valuable in their own right. This changed outlook is also a lesson drawn from what has been experienced in the history of the 20th century.

Despite Otto Weininger and his positively racist hatred of women, despite Sigmund Freud and his overemphasis of hysteria as a female phenomenon, more and more intellectual women spoke up, were not to be deterred in their convictions and gathered like-minded companions around them. Women were no longer willing meekly to accept what life brought them, they refused to be disciplined by society, to be reduced to ‘the female nature’. They cancelled their contracts as lovely mirrors, as decorative background for men.

As the general view of life became more rational, the longing for irrationality found increasingly vehement expression. Salvation ideologies were having a field day. The cultural pessimism of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) and the strange and absurdly hopeless world of Franz Kafka (1883–1924) are crystallised manifestations of the collapse of customary edifices of ideas. Wittgenstein thought that it was everyone for himself now that socio-cultural order had broken down. Arthur Schnitzler (1862–1931), physician and playwright and, thus, twofold therapist of his world, portrayed Viennese society on its way to decline and death.The underlying mood was one of hopelessness and resignation.

This element of Vienna Modernism and, particularly, its literary heroes, reduced women to sexual creatures, to mirrors reflecting admirable male qualities. Peter Altenberg (1859–1919), an admirer of girlish femininity, very clearly delineated the boundaries for women. He explained what they should be like: ”... A woman has to be for us in some way like an Alpine forest, something that exults us and frees us from our inner enslavement, something exceptional that gently and instinctively leads us to our own heights, as a good fairy guides the poor lost wanderer in the fairy-tale. ...“

Viennese romanticists were incorrigible pessimists, for all the decorative and erotic élan that formed the surface of their art, whereas the Constructivists, with their vision of the artist-engineer, enlisted art in the service of the brave new geometrically correct (not to say rigid) technological society that would save us from our all-too-human selves. No doubt the abstract geometry was refined, giving their art a certain reductive elegance, but it made no sense apart from its idealistic social purpose.

“These artistic opposites never met; they represent the severed halves of 20th century thinking about the human condition. The tragic humanists tell the emotional truth about it, the utopian Constructivists offer technological hope in what seems like a hopeless historical situation. The former are conservatives, in that they see the failings of humanity, which they regard as inevitable, while the latter are re

tionaries, looking for social miracles in a mundane world. For the former, avant-garde art is a new way of stating old insights into human existence, and thus making them seem fresh, while for the latter avant-garde art is a fuse that will help ignite social revolution, even as it shows that art can keep up with scientific and technological revolution, the bright side of modernity.” ( Donald Kuspit )

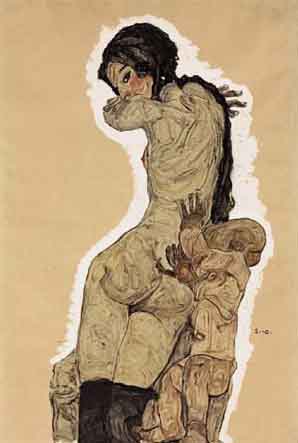

The wild young painters put an end to this alliance between truth and beauty, creating a new unsettling and exciting concept of beauty and ruthlessly discarding Secessionist aesthetics. Schiele annihilated the concept of beauty upheld by the Jugendstil artitsts, at the same time abandoning the concept of goodness inherent in the concept of beauty. Expressionists do not hesitate to depict people torn between extremes. Provokingly and ecstatically they commit to canvas the tension of the moment. Egon Schiele’s themes are Eros and Death.

The representatives of Modernism did not want to their conception of art to be seen merely as a contrast to former

trends or styles, i.e. as a normal change when one generation succeeds another, but they also wanted it to gain recognition as a futuristic principle. Like the concentric circles which ripple outwards from a stone thrown into water, Modernism in Vienna was first mentioned in the essays of Hermann Bahr, then went on to conquer literature, exert a shaping influence on the visual arts in the Secession movement and pave the way for Expressionism, which set out to progress beyond Modernism in the decade after 1900. Hermann Bahr himself declared later that he had erroneously mistaken the red hue of the sunset of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy for the first flush of dawn.

For instance, in the exhibition of 1908/09 it was no longer one of the doyens of art, such as Klimt, who created a public stir, but the young Expressionists Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka. Just how much of a public outcry they caused may be gleaned from a remark made by the heir to the throne, Franz Ferdinand (1863–1914), who said, in reference to one of Oskar Kokoschka’s works presented in an exhibition at the Hagenbund in 1911, that one should break every bone in that fellow’s body. At any rate, the Secession was a forum for young artists who did not comply with fixed expectations but went radical new ways.

Klimt, too, had painted sexual themes, but through the use of ornamentation they were stylised. Schiele violated the prevailing artistic canon both in form and substance. There is nothing he finds embarrassing and especially his nude drawings are blatantly realistic.

Violent reactions were occurring in every branch of the arts. The intensely modern writer Franz Kafka, born in Prague in 1883, reached artistic maturity in the phosphorescent twilight of the hapburg empire. Kafka only came to Vienna to die. Nevertheless, from his understanding of the fading empire, he established two characteristic modern themes at an early date: the estrangement of twentieth-century man and his domination by anonymous forces he does not understand. These themes reach their fullest expression in his novels “The Trial” and “The Castle” , where the isolation of modern man is most complete.

Rudolf Leopold calls Schiele and Kokoschka expressionistic artists who incorporate the ugly into their works with a view to enhancing their emotional impact. An artist such as Kokoschka thus confronts the beholder with a disrupted and sick counter-world. His perspective of the world shattered every expectation of beauty, grace or glossy superficiality

Music , however, was the characteristic means of expression in Vienna. And it is in music that one can see the most obvious reflection of the end of an era and the subsequent search for new values. It was Schoenberg who turned most clearly in the direction of the new world, rejecting the traditional forms of music and looking far into the twentieth century. His “Verklarte Nacht” was first performed as a string sextet in 1899, and while Gustav Mahler and Bruno Walter applauded, others hissed and shouted in derision. In 1905, a contemporary critic referred to his “Pelléeas et Melisande” as a “fifty-minute-long protracted wrong note.”

The musicians and artists and writers who came forward in the last days of imperial Vienna saw that the old rule no longer had application. New ones would have to be found. And in the seemingly carefree life of the dying empire they anticipated many of the intellectual problems of the later twentieth century. They saw what most of their contemporaries did not: that a new world was waiting beyond the great divide of 1914.

Yet even the rebel Kokoschka went off to the last of the wars of chivalry, dressed in the uniform of the 15th imperial dragoons: red trousers and a light blue jacket, a golden helmet , and tall white thigh boots. And the Good Soldier Schweik asked: “Those uniforms with gold buttons, the horses, the marching men- you mean to say you sent something as beautiful as that to war?” They did, and that war effectively finished the old Europe. With startling speed the symbols of the “ancien regime” dissolved and vanished.

ADDENDUM:

Donald Kuspit: Schiele’s drawings of the female nude are about his profound ambivalence toward woman. His attitude is typically male: He is drawn to her outer appearance, but disappointed by her “inner” reality. To glimpse the vaginal slit that is hidden under her skirt, indeed, to boldly stare at it, is to become deeply disillusioned. To penetrate the mystery is to discover there is none — it’s all in man’s fantasy. Freud writes that sustained fascination with the vagina is perverse, but while Schiele is perverse, he is also coldly realistic and descriptive — a detached observer. His infantile sexual curiosity has been satisfied — a kind of peeping Tom looking underneath woman’s skirts, he has satisfied himself that what women have between their legs is very different from what men have, and inferior to it (they are, after all, “castrated,” and the 1911 nude may be about his own castration anxiety) — but the revelation is not as exciting as it is supposed to be. So much for woman’s beauty and mystery. Schiele’s images debunk these idea, showing that woman is ugly and dangerous, physically and emotionally, underneath.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS