Early twentieth-century Viennese modernity, obsessed with identity in crisis, was especially preoccupied with the play between external appearances and internal dimensions of the self. How could it not? No doubt, all roads eventually lead to Freud as part of the explanation of artists like Schiele and Kokoschka who were attacking traditional forms as Picasso and Braque were doing in France. He lived in Vienna and, by 1910, when they were emerging, he had already written about hysteria (1895), dreams (1900) and sexuality (1906), all of which are involved in their pictures.

"The clothed Seated Couple (1915) shows a limp, mentally ill man, who looks like a broken doll, embraced -- held together -- by a strong if unhappy woman. "

There was a deep and profound pessimism; sexual relationships were invariably tragic, and by extension, human relationships fared no better. The visual arts were depositories, resting places for morbid, fugitive imaginations. Despite the veneer of moral shock and outrage, the gender politics of this new art seems to confirm the old patriarchy, and perhaps even reinforced it. Freud’s reluctance to confront the epidemic of incest seemed to only easperate existing pathologies which simply became more legitimate.

In male art, these contradictory meanings seemed to converge on the vagina, suggesting that, for all, for example Schiele’s and others fascination with woman’s sexuality, they were afraid of it: Women are, for all their seductiveness and charms, a defective, diseased, hysterical animal.

Kuspit:Alfred Kubin's drawings epitomize the nightmarish, uncanny "other side" of Viennese tragic humanism, to refer to his novel Die Andere Seite (1908). It is full of the same perverse reveries and grotesque imagery that appeared in his visual art. Kubin's work involves the same ambivalent misogyny and emotional violence that we see in Kokoschka and Schiele, even as it surpasses them in visionary extravagance. Its horrific, grim fantasies...

The art reflected the behavioral and cognitive sciences which were tinkering with the explosive issue of identity: Human beings are about the struggle to transform the self — an incomplete process, in which the individual struggles to free themselves from their suffering, that is, to heal themselves,to reconcile, to accept, but, often fail to because they are unable truly to relate to one another, establishing what Michael Balint calls a “harmonious mix-up,” a kind of back to the garden quest where there is no distinction between the self and other. Collectively, and at its marginal level, they envision a world that is the opposite of that of modern science and technology: one that is driven by human irrationality, animal instincts and supernatural forces.

Oskar Kokoschka - Pieta, 1908, 1909 Poster created for the open-air theater of the Kunstschau, depicting Murder, Hope of Women

There were too many harsh facts that the pageants of Imperial Vienna could no longer obscure. Three of them combined to destroy the Habsburg monarchy: the poverty of the masses, the demands of a new industrial civilization, and the growing pressures of nationalism. The Austro-Hungarian Empire, for all its panoply and glamour, was little more than a “prison of peoples.” In a hundred different ways life in the imperial city illustrated the conflict between the ancient dynastic order and those new forces of progress and freedom that had been conceived in the eighteenth century. It was a conflict apparent at this time in all the countries of Europe- at least in retrospect.

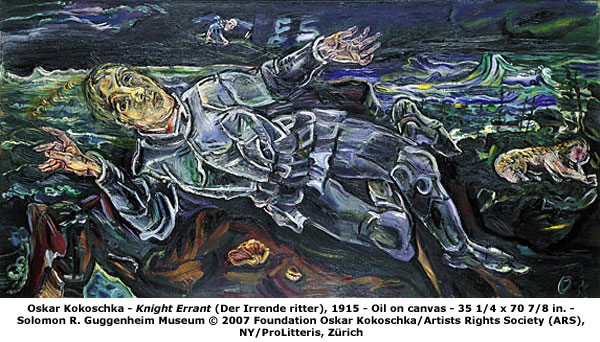

Oskar Kokoschka. The Tempest. Angela Dilkey:Their torrid love affair is thoroughly documented in his artwork, and Kokoschka refers often to this painful time in his subsequent drawings. Kokoschka completed numerous drawings and paintings of or for Alma Mahler, each one expressing his feelings for or about her at the time. One of Kokoschka’s most important paintings was Die Windsbraut or The Tempest. This painting, originally titled “Tristan und Isolde” after Alma’s favorite opera, was what Kokoschka thought was his strongest and most important work, a masterpiece of expression.

But the artificiality of Imperial Vienna served to set this conflict in bolder relief than in many other places. It is a pradox that some of the most “modern” trends in European art and thought appear for almost the first time against the painted backdrop of Franz Josef’s city. The explanation may lie in the very artificiality of that city. As the painter Oskar Kokoschka maintained, the old empire was something magnificently concrete to react against.

His career is a perfect illustration: he was forced to leave the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts after the scandal of the first “Kunstschau” in 1908. Kokoschka’s work was not only a reaction against the worn-out salon art of painters like Hans Makart. It was, as well, a reaction against the decorative Art Nouveau of Gustav Klimt. Klimt’s lush and elaborate paintings such as “The Kiss” is an illustrat

of the dead end that Viennese art had reached by the beginning of the twentieth century.

"While Klimt’s paintings still exude the perfume of the nineteenth century, the work of Schiele and Kokoschka looks entirely modern. Their portraits depict faces we might easily encounter on the street today; the erotic tensions expressed in their work reflect concerns we have acknowledged for many decades. Taken as a group, Klimt, Schiele and Kokoschka document the transition from an old century to a new one. All three artists welcomed change as an invigorating, liberating force. Yet when change finally came to Austria, it brought much destruction and pain. The Austro-Hungarian Empire did not survive World War I. The old Emperor died, and in 1918 his successor was deposed. Schiele and Klimt, too, did not survive the end of the war. Only Kokoschka lived to see the Austrian government overthrown once more, by Hitler in 1938."

Kokoschka, born in 1886 of Czechoslovak and Austrian parents, had been influenced to a certain extent by the French impressionists, whose work was being exhibited in Vienna for the first time at the turn of the century. Like them, Kokoschka wished to emphasize that art was related to everyday life and concerned with its realities. It is also apparent that Kokoschka wished to “startle the old fogies.” And the poster he designed for the 1908 exhibit did just that: it had a religious theme, a brutal “Pieta” depicting a woman “red as a leech with a dead-white Kokoschka on her knee.”

The architect Adolf Loos bought a clay head that Kokoschka had made for the exhibition. It was covered with veins and a network of nerves and was scarcely appealing in any decorative sense. But Loos saw in Kokoschka the expression of a new era. The young painter became notorious overnight: the newspapers objected to his work, and the middle class looked upon him as an illustration of the irresponsibility of modern art. But in a city where lassitude and overrefinement were producing stagnation, Kokoschka was expressing a vital optimism for the twentieth century. In the city of wedding cake formalism Kokoschka was vehemently bent upon destroying traditional forms.

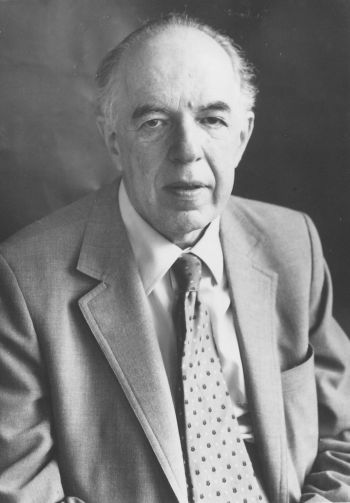

Ernst Gombrich:I used to think I was a Viennese, or an Austrian, but then a large number of my fellow citizens discovered that I was a non-Aryan, and they would have treated me accordingly if I had not been out of their reach. Meanwhile, after half a century, well-intentioned people are evidently seeking to convince their compatriots that 'non-Aryans', or Jews, are not baddies, but goodies who contributed to the glory of Vienna, or actually created it. I share the opinion of my late friend Karl Popper, that intellectuals have much to answer for, now, as in the past. We know how often they have invented and fostered collectivist myths. If I may close with the words Popper used: 'I consider any form of nationalism to be criminal arrogance, or a mixture of cowardice and stupidity. Cowardice, because the nationalist needs the support of the crowd - he does not dare to stand alone - stupidity, because he considers himself and his ilk to be better than others.

ADDENDUM:

In recent years a growing amount of scholarly writing about Austrian culture and the extraordinary intellectual splendour of Vienna around 1900 has concentrated on the Jewish background of many of Austria’s intellectuals. The Anglo-American historian Steve Beller’s work high-lights the ethical and educational influences of the Jewish enlightenment tradition. He interprets the phenomenon of ‘Vienna 1900′ as a reaction by Jews to partially failed attempts to integrate and to assimilate into Viennese intellectuals, but that the crisis of identity felt during the late Habsburg Monarchy can mainly be traced back to the experience of Jews caught in the dilemmas of assimilation.

Ernst Gombrich challenges this position. His lecture questions the relevance of the concept of Jewish identity to the cultured Jews of the turn of the century. He rejects any kind of collective ‘national’ myth. Born in 1909, in Vienna, Ernst Gombrich grew up in an assimilated Jewish family and educated in the traditional German humanism.

Donald Kuspit:Indeed, the astonishing thing about Kokoschka and Schiele's portraits is that they convey suffering and spirituality simultaneously. In Kokoschka's double portrait of Hans Tietze and Erica Tietze-Conrat (1909), the figures, for all the anxiety visible in their troubled gestures and furtive glances -- their quivering hands and inward-looking eyes -- are spiritual beings, as their luminous flesh, marked by golden striations, in effect radiant emanations, indicates. Kokoschka depicted madness, as in his portrait of Ludwig Ritter von Janikowsky (1909) -- in a mental hospital at the time -- but it is madness conscious of itself, and thus in a sense spiritualized. It is a face in hell, reminiscent of Munch's portrait of himself in the same infernal place, but it is also full of inner light, breaking through its gloom. It is the face of death and damnation, but also of eternal life. Light and dark mix inextricably in Kokoschka's portrait, the light breaking through the ash of the dark, the dark suffused with uncontrollable light.

The discussion which followed his lecture brought Gombrich’s insight into contact with contemporary concerns, not to say anxieties, about the issues of identity and difference. It evoked the question of whether it is possible to assume a collective identity (be it Jewish, Austrian or British) without claiming the superiority of that identity over other, and of the role of intellectuals in the ‘invention’ and perpetuation of the ‘national myths’ which have so often in history led to disaster. I think Gombrich is right when he points out that collective identity and the feeling of superiority cannot be separated. But there may be strategies of controlling the negative consequences of ‘national’ myths.

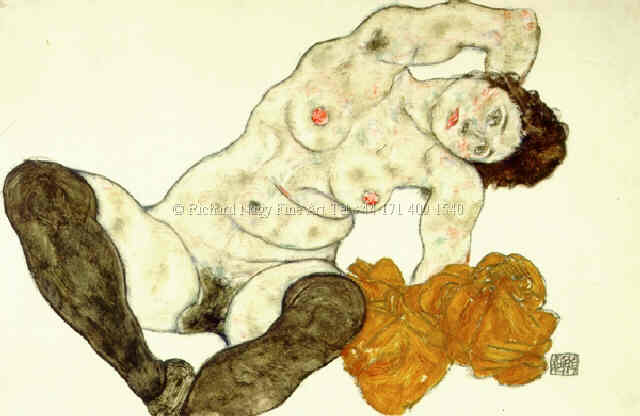

Kuspit:Schiele's sinuous nudes have a similar hysterical intensity and unbalanced character. For all their clinical clarity and candor, they also have a nightmarish quality, however subliminally: Schiele's nudes are femme fatales, teasing one with one's own frustration. For example, the Reclining Nude with Yellow Towel (1917), who has her head tilted to the side so that it becomes horizontal, seems about to fall over. The diagonals of her dark stockings draw us toward her vagina, marked by dark pubic hair, a vertical accent at odds with the horizontal accent of the dark hair of her head. She may look at us quizzically, as though we are odd, not her -- she may even be demented, as her position suggests, implying that we are demented for being interested in her nakedness -- but the sexual invitation is there. Schiele's nudes have been wrongly understood to be pornographic. The psychoanalyst Robert Stoller points out that pornography dehumanizes the human body, while Schiele's figures never lose their humanity. Their sexuality is, in fact, inseparable from it, and makes it all the more profound by signaling its tragedy; the delicately tinted vaginal slit that is the focus of the image of a notorious 1911 nude -- she seems like an innocent child -- reclining on her front, mars the whiteness of her skin, suggesting the tragedy of being a woman, and of human life in general, which depends on sex to propagate itself. This work, like all of Schiele's drawings of female nudes, is about the tragic character of sexuality. Sexual relationships are tragic, and so are human relationships in general.

Ernst Gombrich belongs to an intellectual tradition which regards historiography is worth the effort in so far as it is capable of resisting the sway of myth. Argument will no doubt continue as to what that tradition owes to humanist, Jewish or Viennese culture. ( Emil Brix, 1997 )

Kuspit: Schiele’s drawings of the female nude are about his profound ambivalence toward woman. His attitude is typically male: He is drawn to her outer appearance, but disappointed by her “inner” reality. To glimpse the vaginal slit that is hidden under her skirt, indeed, to boldly stare at it, is to become deeply disillusioned. To penetrate the mystery is to discover there is none — it’s all in man’s fantasy. Freud writes that sustained fascination with the vagina is perverse, but while Schiele is perverse, he is also coldly realistic and descriptive — a detached observer. His infantile sexual curiosity has been satisfied — a kind of peeping Tom looking underneath woman’s skirts, he has satisfied himself that what women have between their legs is very different from what men have, and inferior to it (they are, after all, “castrated,” and the 1911 nude may be about his own castration anxiety) — but the revelation is not as exciting as it is supposed to be. So much for woman’s beauty and mystery. Schiele’s images debunk these idea, showing that woman is ugly and dangerous, physically and emotionally, underneath.

Kuspit: The Family (1918) is a rare picture of human and sexual harmony, although the naked figures are vagabonds exiled to a dark void. They are all deeply troubled -- the man's suffering is evident in his disjointed body, the woman keeps her suffering to herself, and the child is becoming aware of his -- however full of hopeful expectation. They look into the distance for some sign of salvation, but it is not clear that any is visible. They are a group portrait of the human condition.

Kuspit:The Tietzes have trouble relating — establishing empathic intimacy — as do Kokoschka and Alma Mahler. Both couples are physically together, but emotionally separate, indeed, at odds. Their highly developed individuality — each portrait amounts to a credo of individualism — keeps them inwardly isolated and apart even as their sexual and social needs and shared interests bring them together. Schiele makes this brilliantly clear in several of his drawings of lesbian couples, who embrace but remain emotionally neutral and unrelated. The people Kokoschka and Schiele portray are too civilized to acknowledge their need for intimacy and love, which is why they seem narcissistic, however morbidly exhibitionistic, that is, however much they show their emotions and bodies to hide their lack of commitment to one another.

Wassergeist."Kubin, aside from being an important artist, was an illustrator and author. He wrote one phantasmagoric novel, The Other Side, and was best known as a prolific illustrator of the works of Poe, Dostoyevsky, and E.T.A Hoffmann. But he was also closely affiliated with the Munich avant-garde of the early 1900s and was a member of the important Phalanx and Blaue Reiter groups. All this despite living a significant portion of his adult like as a near recluse."

a

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS