Perhaps the most striking characteristic of a child’s art is that it cannot go wrong. There are no bad drawings by children; in the same way, there are no bad paintings by Joan Miro. The German dramatist Heinrich von Kleist once told the story of a duel between a man and a bear: not only did the animal ward off every thrust of the sword, but he never fell for his opponents feints- in fact, he seemed not even to suspect them. It is the infallibility of innocence.

Bourgeois:In fact he was a prolific workaholic. However, he was also sensitive and vain. He was surrounded by people who praised him, and he liked that. When they told him what he was doing was marvelous, he went on doing it, like a good student. Miro wanted to be encouraged, and when he was encouraged he was like a child. His move to Paris was not altogether positive; in his early Catalan landscapes and portraits, and his very early abstract work, there was a deep emotion that seems to be lacking in his later years. We know that he was strong enough to shake off the hold of Breton--that he objected to anyone dictating his style.

Miro’s color, no matter how free an unpredictable , is always rigorously right, like the acid harmonies of a duck’s plummage or a piece of rock. Supremely right too, is his line, like the flight of a bird, or the patterns made by water spilled from a glass, or the sinuosities of a cowboy’s rope about to snare a cow. Sculptor Alberto Giacometti once called Miro “truly a painter”, which is what distinguishes Miro from the child. Indeed there lies the source of a profound conflict. For painting is an adult activity. It is not surprising therefore, that the realm of childhood is usually forbidden ground to artists. When they trespass upon it, they become childish, not childlike. That is the reason for Miro’s secret, for the elation that is so specifically his own.

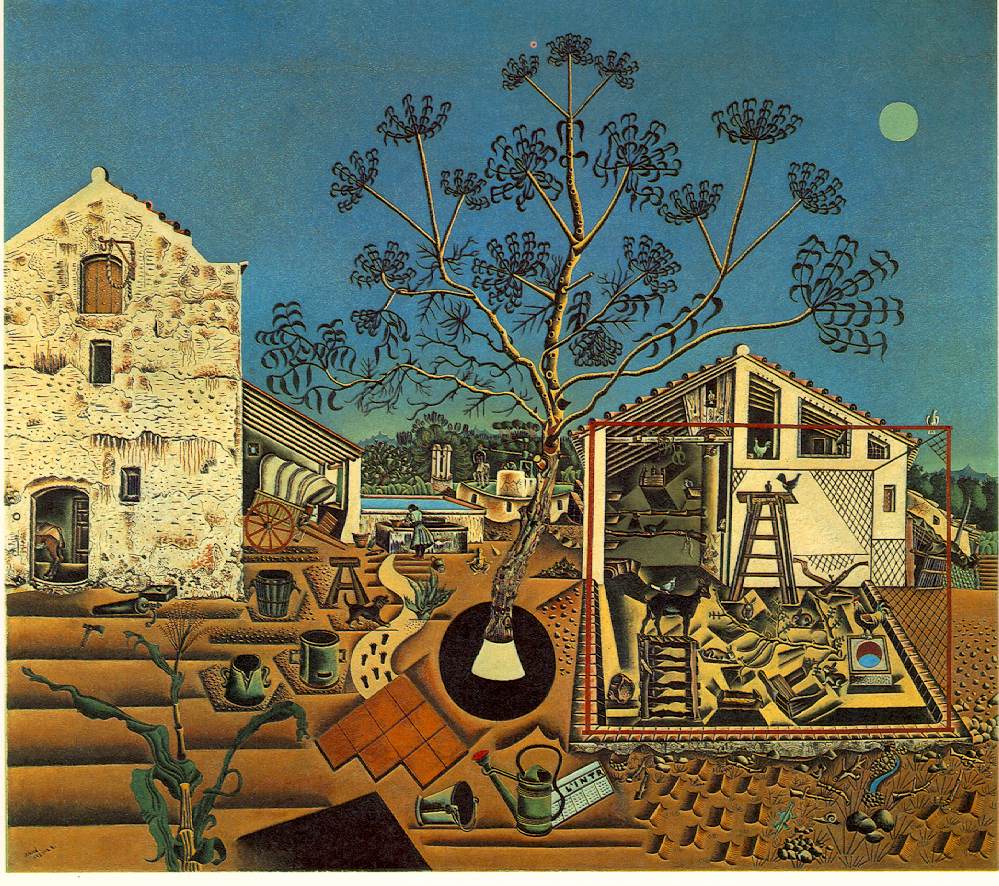

"The person who is eager to please becomes an overachiever. He is not an ambitious person, for he has no relationship to a larger context, to the world of ideas. He has nothing to do with the Olympus complex; he has no notion of "pie in the sky"; the people he wants to please are those he knows and loves. His intensity is ferocious but localized, and therefore safe. Miro was successful. He found a formula and went on doing it for fifty years. After all, he had to sell."( Bourgeois) The tilled field 1923-24

“There is a type of artist who wants to appear naive–Alfonso Ossorio, for example, or Jean Dubuffet, or even Philip Guston. Whereas the genuine naive, though truly talented, is helpless, the faux naive is a crafty one. Anything will do to serve his ambition to seem naive. It is rare but not painful to have talent; you either have it or you don’t. It is, however, laborious and painful to want to seem to have talent. The risk is great: the faux naive may fail to convince, may be perceived as coy. Dubuffet is not Adolf Wolfli–one is a put-on and one is genuine.

Miro was a true naive, trusting, unable to take two steps without his supporting family. When I knew him he always replied to every question, “I’ll have to ask Pilar,” his wife. His large brown eyes were innocent and serene. He was a truly naive person in the best sense of the word: someone who could not grow up. He was what he was and did not pretend or want to be anybody else. He believed in himself, and that is a great compliment. He really accepted himself. In the true naive there is no discrepancy between the person and the work. Miro was his work.” ( Louise Bourgeois)

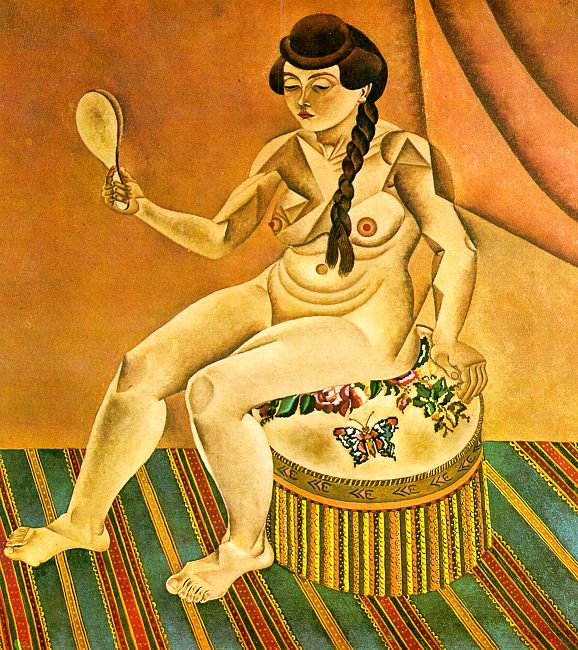

Robert Rosenblum: In 1967 Invited to the Kinsey Institute for a symposium on erotic art, I prepared a paper on Picasso's work of the Surrealist years, and soon discovered that Miro played an essential role in the story. Miro's ubiquitous genitalia, desperate copulations, and burgeoning, metamorphic maternities all had to be seen as part of an ongoing dialogue with his more famous compatriot. The sexual charge I had intuited as a teenager in 1941 unexpectedly resurfaced, this time in analytic, professorial discourse....

Even more fully than Paul Klee, Miro placed a mature skill at the disposal of a primitive imagination. And this unique conjunction reopened for us the road to what Baudelaire called the green paradises of childhood. In appearance, nothing could stand in greater contrast to Miro’s work than Miro himself. His art is extravagant; the man was the incarnation of propriety and sobriety. Correct in dress, quiet in behavior, meticulous in his routines; he resembled less an artist in the popular conception than a good church goping bourgeois. To anyone who knew Miro’s painting, the opposition was comically startling- though the humour was always perfectly unintentional, Miro, even in his most exuberant fantasies remained grave. Like children , he played, but his games were in dead earnest. But Miro was actually following a certain logic. As the depository of a fragile treasure- a childlike purity in a world of grownups- he knew that he must take pains to preserve it: pretend to play the game behind a demure facade, then take off for Mars and Venus.

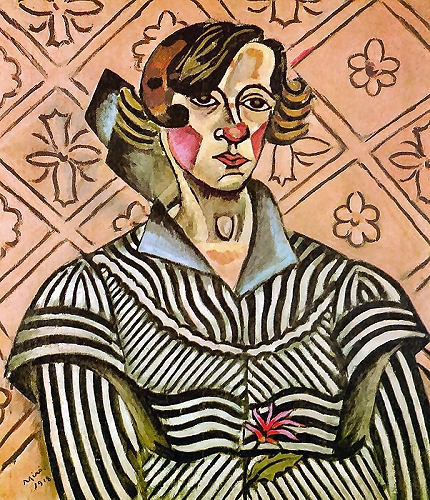

Portrait of a Spanish Dancer. 1919. "Picasso wanted to touch every female body. In his strivings we sense his fear of losing his own desire; his sensual gluttony feels like torment. Miro was as locked into the physical as Picasso was, but he avoided torment by avoiding the sensual. He accomplished this by transcribing the physical into the linguistic. The erotic puns in Miro are not expressions of his desire for a subject, but transformations of a subject into a whimsical sign system that desensualizes all it replaces."

His early works in Paris could be characterized as strangely anarchic and deliberate. In them, nature bulges and sways ominously; the works have some of the frustrated fury of Van Gogh. They are powerful, moving , sometimes considered failings that Miro attributed to the fact that reality still eluded him. By 1922, Miro had felt he reached a dead end where reality had freezed into a pillar of salt. In an ultimate attempt to capture reality , he painted “The Farm.”

“The Farm” is a compendium, a summa of all that mattered most to Miro: a collision of ancestral opposites. It took Miro nine months to complete “The FarmR

, which Ernest Hemingway acquired shortly after. It was an ending, but also a beginning. All the elements that we encounter later in emancipation, are present here, but still shackled. It was as if Miro had unconsciously compiled the glossary of a language which he was soon to speak. By 1924 the decisive step had been taken: Miro painted “The Tilled Field.” Miro had found his signature; his road to Damascus.

The Farm. Nesbit:Miro's break and subsequent blossoming obviously didn't occur in a vacuum, but they have a special quality. He was close in spirit to the prehistoric artists of Altamira and Lascaux; the impulses in the work seem "human" rather than "Modern" or "European." There is a wonderful comfort with playfulness and sexuality in the work. He achieved a scale and an openness several generations ahead of the conventional wisdom in painting, and he integrated language into his imagery through the collapse of writing and drawing into one activity. The implications of all this are still being explored.

ADDENDUM:

The outer world, the world of contemporary events, always has an influence on the painter — that goes without saying. If the interplay of lines and colors does not expose the inner drama of the creator, then it is nothing more than bourgeois entertainment.

The forms expressed by an individual who is part of society must reveal the movement of a soul trying to escape the reality of the present, which is particularly ignoble today, in order to approach new realities, to offer other men the possibility of rising above the present. In order to discover a livable world — how much rottenness must be swept away!

The Hunter. 1923-24. Rosemblum:1980 Asked to give a lecture to accompany Sidra Stich's innovative exhibition "Miro: The Development of a Sign Language," at Washington University, I pulled together, in a broad sweep, "Miro, Picasso, and the Spanish Grotesque." This freewheeling theme gave me a chance to wallow in a vast sea of Iberian ancestors, from paleolithic paintings at La Pileta and Altamira to Catalan Romanesque frescoes, from Philip II's passion for Bosch to the subhuman inventions of Goya, and then, inevitably, on to the Spanish Civil War. After Franco's death in 1975, Spain seemed reborn, and Miro looked more Spanish or, rather, more Catalan than ever. 1988 Miro's Dog Barking at the Moon, 1926, was, of course, essential for my little book on the dog in Modern art. On investigating the preparatory drawings I realized that Miro had in mind not only folkloric proverbs and the nightmare world of Goya, but comic strips a la Krazy Kat. A precocious Pop artist?

If we do not attempt to discover the religious essence, the magic sense of things, we will do no more than add new sources of degradation to those already offered to the people today, which are beyond number.

The horrible tragedy that we are experiencing might produce a few isolated geniuses and give them an increased vigor. If the powers of backwardness known as

fascism continue to spread, however, if they push us any farther into the dead end of cruelty and incomprehension, that will be the end of all human dignity.

Joan Miró, “Statement,” 1939

Read More:

http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/kuspit5-23-06.asp

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_n5_v32/ai_15143622/?tag=content;col1

http://www.earlham.edu/~vanbma/20th%20century/images/daynineteen.htm

COMMENTS

COMMENTS