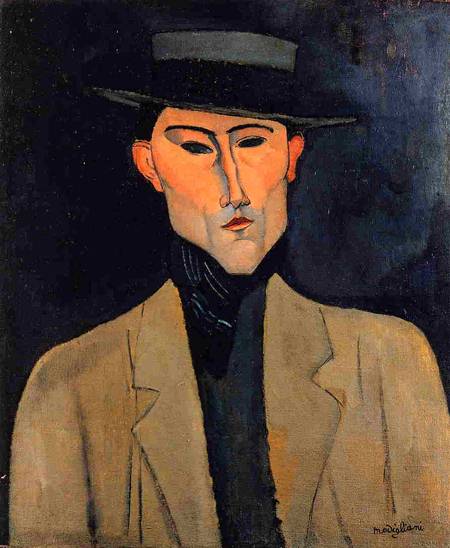

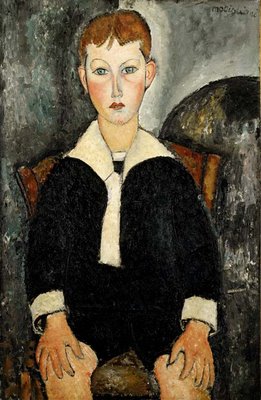

The theory of Donald Kuspit and a few other less known voices was that Modigliani rehumanized what Picasso had crushed and sucked out. Modigliani was able to connect in his paintings to those live and unpredictable wires – the curse of suffering- and bring out the human in all its elan and moxie and grit and hope and place it in a new context liberated from the ordinal rankings of social distinction to which the viewer rediscovers something lost and now tarnished but still serviceable.

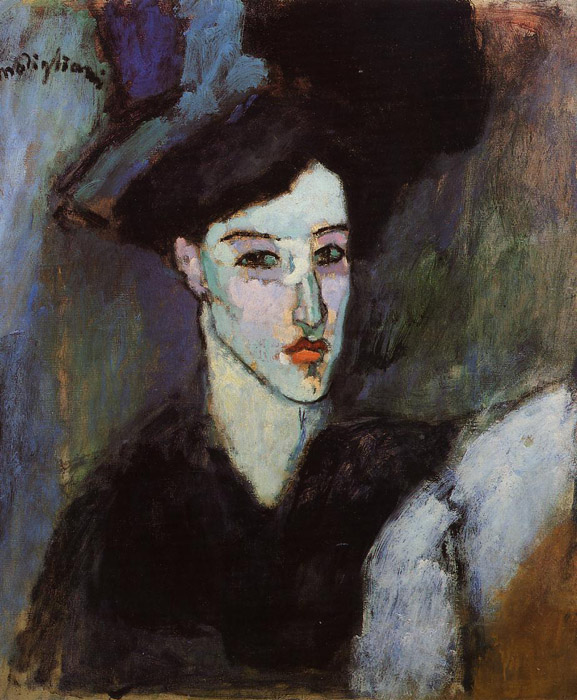

---Anna Zborowska. 1908. ---The dictatorial idea of absolute art was inimical to his libertine instincts and spiritual ambition. It was a betrayal of the imaginative potential of art, falsifying it by implying that it had no transformational effect on human beings and nothing to do with the human condition. Ortega observed that there was a ban on pathos in Cubism, but Modigliani lifted the ban, or rather refused to accept it just as he refused to accept the dehumanization of human form. He has been said to be a failure as a modernist because he was attracted to the Old Masters -- Clement Greenberg said the same thing of Soutine -- but the Old Masters represent pathos and humanness, and pathos -- the pathos of being human -- was what Modigliani and Soutine were after. --- Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazine/features/kuspit/kuspit7-27-04.asp

For Modigliani, paint is the empathic matrix in which the suffering figure exists, even as its schematic form gives it a spiritual aura that seems to reconcile it to its suffering, or at least works like a charm against the curse of suffering that contaminates life. Stoically self-contained, Modiglianis figures seem to have mastered tragedy, however tragic they look….Or rather Modigliani refused to dehumanize the figure in the name of form, that is, to achieve a formal rigor that seems superior to the informal figure and more artistically authentic by reason of its supposed autonomy. For Modigliani form was a way of bringing out and accenting inner human qualities, rather than some intriguing pure thing in itself. Austerity of form was a betrayal of the feeling of being human — and the feelings human beings had — for Modigliani. ( Kuspit) Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazine/features/kuspit/kuspit7-27-04.asp

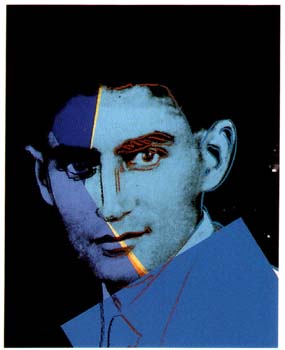

---In a letter, Kafka once defined himself as a “typical example of a Western Jew,” later stating, “This means that I don’t have a moment of peace, that nothing comes easily to me, not just the present and the future, but even the past, that thing that each man receives as his birthright: even that I have to conquer, and perhaps that is the hardest task.” His frustration and morbidity—features now defined as “Kafkaesque”—clearly relate to the internal struggle he had with his Jewish identity.--- Read More:http://momentmagazine.wordpress.com/2011/03/24/kafkas-jewish-ghosts/

The connection of Modigliani with Kafka seems obvious today; particularly through the Kafka story, The Hunger Artsist, a kind of reflection on an antagonistic relation with our bodies as a foreign entity, a metaphor for Kafka and a quest for identity and the peculiar shape of the human form in Modigliani where the figurative is defined by volume and boundary rather than an interconnectedness with flesh and bone. In the Hunger Artist, the man lives in a cage with dirty straw and after he dies a panther is put in the cage. I can see where this idea of coexistence arose in Moacyr Scliar and his famous Max and the Cat story. To what degree does identity battle to define itself independent of institutional sanction and what Kafka called the “claustrophobia of labels” affixed by the gaze of outsiders. Kafka and Modigliani were basically ignored, but they went beyond their identity and like Hunger Artist’s starved and thrown to the animals in a cage. Both were at odds with the futility of life, and were not willing to flatten, distort, scrunch and dehydrate the individual like Picasso.

To die would mean nothing else than to surrender a nothing to the nothing, but that would be impossible to conceive, for how could a person, even only as a nothing, consciously surrender himself to the nothing, and not merely to an empty nothing but rather to a roaring nothing whose nothingness consists only in its incomprehensibility. –December 4, 1913…What have I in common with Jews? I have hardly anything in common with myself and should stand very quietly in a corner, content that I can breathe –January 8, 1914 ( Kafka diaries)

---“Because,” said the hunger artist, lifting his head a little and speaking, with his lips pursed, as if for a kiss, right into the overseer’s ear, so that no syllable might be lost, “because I couldn’t find the food I liked. If I had found it, believe me, I should have made no fuss and stuffed myself like you or anyone else.” These were his last words, but in his dimming eyes remained the firm though no longer proud persuasion that he was still continuing to fast. “Well, clear this out now!” said the overseer, and they buried the hunger artist, straw and all. Into the cage they put a young panther. Even the most insensitive felt it refreshing to see this wild creature leaping around the cage that had so long been dreary. The panther was all right. The food he liked was brought to him without hesitation by the attendants; he seemed not even to miss his freedom; his noble body, furnished almost to the bursting point with all that it needed, seemed to carry freedom around with it too; somewhere in his jaws it seemed to lurk; and the joy of life streamed with such ardent passion from his throat that for the onlookers it was not easy to stand the shock of it. But they braced themselves, crowded around the cage, and did not ever want to move away. ---- Read More:http://www.lundwood.u-net.com/ahunga.htm

Nonetheless, Modiglianis humaneness gave him access to his sitters feelings, no doubt partly by way of projective identification, but also by way of a larger awareness of the human condition. He did not simply aggrandize figures as tropes for some one-dimensional feeling, as Picasso did. Modigliani saw through people to the pathos within them, transforming their appearance just enough to convey it, without destroying their dignity, as Picasso did. Where did Modiglianis sensitivity to others — his respectful response to human beings, whether at their most sensually exciting, as in the odalisques, or at their saddest, as in The Jewess (1908) — come from? His Jewishness. Modigliani was a Sephardic Jew with mystical inclinations, as has been argued, but I want to emphasize the moral rather than mystical side of Modiglianis Jewishness. The mystical is secondary to the moral in his art, however evident it may be in his limestone heads. Just as Chagalls Jewishness led him to maintain a sense of moral commitment while working in a modernist manner — he even integrated them, as Meyer Schapiro argued in his essay on Chagalls Illustrations for the Bible, a rare feat because of modernisms tendency to idealize form at the expense of the human and communal — so Modiglianis Jewishness gave him an enduring respect for human experience that gave him the esthetic strength to resist its subsumption, not to say complete submergence, in the experience of form, which is exactly what occurred in Cubism.( Kuspit) Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazine/features/kuspit/kuspit7-27-04.asp

---The Hunger Artist had been suffering from bouts of depression and is found nearly lifeless in his cage because he never found what he wanted to eat. The impact of this conclusion blindsides the reader, and yet the foundation for such an outcome is entirely plausible. The Hunger Artist starves himself to death because his inability to find the food he wants is similar to the depression that afflicts millions within the world. As the artist simply cannot eat, the depressive simply cannot get happy. The jubilant panther mirrors life’s common bystander to those afflicted by depression, jumping about and progressing through its days with avidity because the hole in its life is always filled with what it wants. On another level of study, the depression insinuated and connected with the caged artist’s separation from society in part symbolizes the rigorous mental anguish of those afflicted with anorexia. The artist trivializes his own behavior and he follows it to the end of his life, and yet the message is anything but trivial, and even more so, it is realistic. Read More:http://dtldobsvtn.wordpress.com/2011/02/06/a-hunger-artist/

ADDENDUM:

Although there is much of a Jewish sensibility in Kafka’s works, there is also a sense of universalism as well. When religion is directly mentioned it’s almost never Judaism being discussed but Christianity. For instance, the Samsa family from The Metamorphosis is quite definitely Christian, praying to the saints, and crossing themselves, and the maid at the end of “The Judgment” buries her face in her apron and cries out, “Jesus!” Also, the tradition of the “wandering Jew” is utilized

he wanderings of K. in The Castle, although in a secularized, more universal way….….It could be that Kafka simply wished that his work be more inclusive as opposed to being exclusively Jewish in nature. The feelings of alienation, being an outsider, and knowing that your life is subject to forces beyond your control, as well as a sense of dogged survival, frequently associated with the Jewish sensibility and which all frequently crop up in Kafka’s work would prove to be among the most widespread and common feelings among people of all religions and races in the uncertain 20th century. In a very real sense, Jewish sentiments have been made universal, and Kafka speaks to these feelings from the perspective of both a Jew and as a member of humanity in general. Read More:http://victorian.fortunecity.com/vermeer/287/judaism.htm

---Amedeo Modigliani (b. 1884 - d. 1920), a near contemporary of Kafka, painted figures bearing a momentary resemblance to the ideal attainment. Viewed at length and dispassionately, they are found to be composed not so much of skin and bone but of volume; typically an egg-like head sits upon a stovepipe neck and so on: a concept from the studio of Constantin Brancusi (b. 1876 - d. 1956) with whom Modigliani had studied until sculpture became too demanding for his frail health.--- Read More:http://www.storyglossia.com/34/as_anorexia.html

he just wanted to have his basic humanity sorted-out. for kafka, ethnic identification was a burden imposed on him by gentile society. no, he did not reject who he was, he rejected, as most jews do or should, the “legal” authority of the “owners” of the identity to grant it or withdraw it from a person in accordance to their own definitions.

Read More:http://www.lrb.co.uk/v33/n05/judith-butler/who-owns-kafka

——————————————————-

A small impediment, to be sure, one that grew steadily less. People grew familiar with the strange idea that they could be expected, in times like these, to take an interest in a hunger artist, and with this familiarity the verdict went out against him. He might fast as much as he could, and he did so; but nothing could save him now, people passed him by. Just try to explain to anyone the art of fasting! Anyone who has no feeling for it cannot be made to understand it. The fine placards grew dirty and illegible, they were torn down; the little notice board showing the number of fast days achieved, which at first was changed carefully every day, had long stayed at the same figure, for after the first few weeks even this small task seemed pointless to the staff; and so the artist simply fasted on and on, as he had once dreamed of doing, and it was no trouble to him, just as he had always foretold, but no one counted the days, no one, not even the artist himself, knew what records he was already breaking, and his heart became heavy. And when once in a while some leisurely passer-by stopped, made merry over the old figure on the board and spoke of swindling, that was in its way the stupidest lie ever invented by indifference and inborn malice, since it was not the hunger artist who was cheating, he was working honestly, but the world was cheating him of his reward. Read More:http://www.lundwood.u-net.com/ahunga.htm

COMMENTS

COMMENTS