In Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, the snobbish Mme de Cambremer at one point exclaims, ” In heaven’s name, after a painter like Monet, who is an absolute genius, don’t go an mention an old hack without a vestige of talent, like Poussin. I don’t mind telling you frankly that I find him the deadliest bore.”

As Proust placed it in time , the remark was made about a century ago, and it symbolizes the disdain with which Poussin’s work was viewed by many people of cultural pretensions, not only then but during the decades before and after. For Poussin, the most renowned of French painters in his own lifetime, had suffered from the most insidious of all evils, or at least one of them: an excess of praise. His seventeenth-century contemporaries acclaimed him pompously as “The French Appelles” and “The Raphael of our century”. He was therefore embalmed in glory;and, petrified by this kiss of death, he gradually became smothered under accumulating layers of prejudice, ignorance and yellow varnish.

Read More: http://hoocher.com/Nicolas_Poussin/Nicolas_Poussin.htm Poussin spent almost all his career in Rome painting in isolation. He endeavored to create a clear visual language that would appeal to the spectator's mind and affect him rationally rather than through the emotions His oeuvre is one of the supreme expressions of classicism in French art. The subject of the Inspiration of the Poet remains under discussion: it is possible that the young man on the right, being inspired by Apollo, is Virgil, and the figure standing on the left Calliope, muse of epic poetry. In both figures there are distinct references to antique sculpture, as so often in Poussin's work, and the golden light shows the influence of the great Venetian painters of the sixteenth century. The appearance of the muse Calliope has led to the suggestion that the picture was painted in honor of a recently dead poet.

Yet, comfortably into the twenty-first century, we are still enjoying the continued revival in, and an admiration for, the art of Poussin, to the point where many critics, assessing in particular his continued exhibitions, have acclaimed him as one of the greatest, if not the very greatest, of all the painters in France’s long, illustrious tradition.

So sweeping a reversal of opinion in a hundred years is unusual in art. It suggest that Poussin, creator of those cool, austere, classical compositions and landscapes which at first glance seem so remote from all present day concerns, nevertheless has something particular to communicate to us today. Long accustomed to regard him as a pious but belated preserver of the Renaissance tradition, we have finally come to recognize in him one of the most influential pioneers of modern art. For this organizer of mythological ballets on canvas also rediscovered nature and in so doing helped create the realistic landscape.

Image: http://babylonbaroque.wordpress.com/2011/08/28/poussin-and-the-exquisite-corpse/ Read More: http://hoocher.com/Nicolas_Poussin/Nicolas_Poussin.htm ---Poussin showed a preference to dealing with subjects such as the sentimental and melancholic scenes from Tasso's "Gerusalemme Liberata", for example the strange encounter Tancred and Erminia in dusky twilight. The scene is played out between two attentive horses - one bay the other white.---

This teller of heroic fables, furthermore, foreshadowed abstract painting- as well as the modern art/craft of cartooning. For he gives us instances both of the former’s reliance on purely formal elements and the latter’s use of miens to reveal psychological states.

To be sure, fellow artist’s over the generations, showed themselves more perceptive of Poussin than has a fickle and capricious public who commonly referred to him as a stodgy academic painter. Yet, the fiercest of romantics, Delacroix, called him one of the boldest innovators in the history of art. John Constable ranked him with Rubens, Titian and Rembrandt as one of the four great masters of landscape. Such widely differing artists such as Corot and Gris, Greuze and Seurat, Ingres and Courbet, Mondrian, Picasso, Pissarro, Matisse and even Rouault have fed on his art; proof enough that it is unusually rich and substantial. Cezanne, who owed particularly much to him said that everytime he came away from Poussin, “I know better who I am.”

Today, almost all obscuring glazes have been removed, and we know better who Poussin is. In his true light he appears as one of the greatest, most complex and varied of painters. For in seeking to maintain the past, he laid the foundations for the future.Indeed, he may well have been the last artist in whom tradition and originality, romance and reality, came to harmonious terms.

Read More: http://hoocher.com/Nicolas_Poussin/Nicolas_Poussin.htm ---In 1643, disgusted by the intrigues of Simon Vouet, Fouquières and the architect Jacques Lemercier, Poussin withdrew to Rome. There, in 1648, he finished for de Chantelou the second series of the Seven Sacraments (Bridgewater Gallery), and also his noble Landscape with Diogenes (Louvre). This painting shows the philosopher discarding his last worldly possession, his cup, after watching a man drink water by cupping his hands. In 1649 he painted the Vision of Saint Paul (Louvre) for the comic poet Paul Scarron, and in 1651 the Holy Family (Louvre) for the duc de Créquy. Year by year he continued to produce an enormous variety of works, many of which are included in the list given by Félibien. He suffered from declining health after 1650, and was troubled by a worsening tremor in his hand, evidence of which is apparent in his late drawings. He died in Rome on November 19, 1665 and was buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina, his wife having predeceased him. Chateaubriand in 1820 donated the monument to Poussin.---

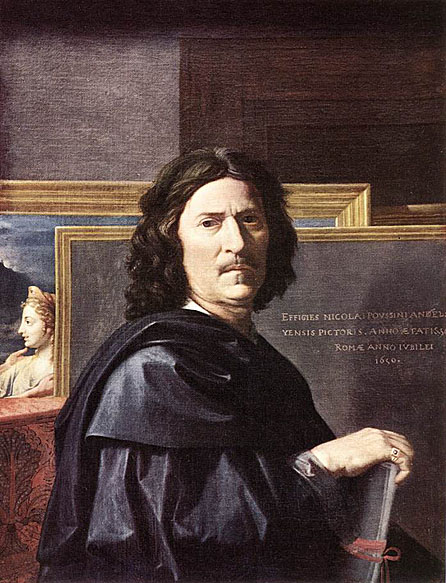

His self-portrait may stand as the symbol of this variety: the stern figure of the artist appears against a background composed of frames, as if to underscore the rational, abstract aspect of his talent, but a counterpoint is created by the female figure on the left, her shoulders clasped by unexplained hands, reaffirming if nothing else, the rights of the imagination and the presence of mystery in a compass drawn universe. Poussin’s work is full of such conflicting tendencies. More exactly, with te

cies that ought to be conflicting and would be anywhere but in Poussin’s painting.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS