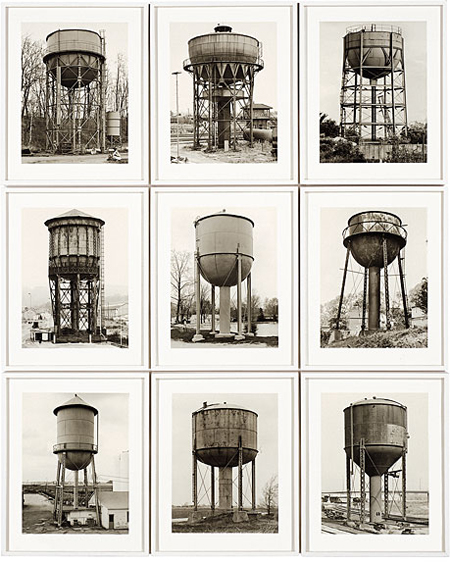

The realistic underside. A commentary on the tenuous grip on sanity that an excess of reason and common sense produce. The dead-end of the escapism into stark materiality. Portrait of a realistic underside of the economic miracle where all the sweepings under the carpet come home to roost. A bleak objectivity. Can an object, a thing, become esthetic by nature of its uselessness. Industrial neglect as a ready-made. Redeeming the nondescript from oblivion. …

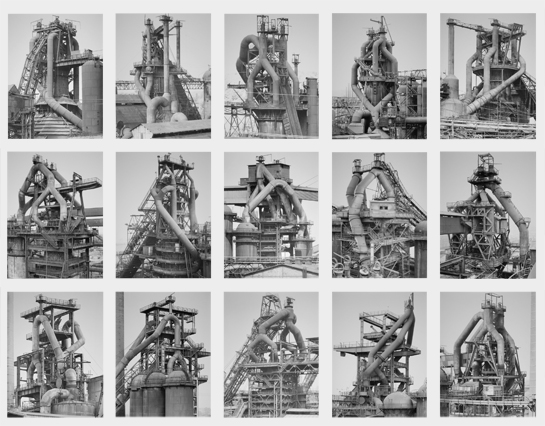

---By creating the circumstances for such experience using aging industrial structures still resonant with the memory of all their great modern ambitions, the Bechers create a powerful sense of that disavowal of instrumental value, that purposiveness without purpose, as Kant named it, as loss, as the experience of no interest where interest was once housed, of no passion where passion once resided. In so doing they give us a fully elaborated neo-Kantian judgment made melancholy, a fully developed archive structured around an absent ideal, and the great promise of Enlightenment is again recovered in all of its original glory but now on the foundation of its own lost materialist soul.--- Read More:http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/04spring/stimson_paper.htm

Among other things, the Bechers’ photographs are a kind of understated social commentary on the German economic miracle (the so-called Wirtschaftswunder of the ’50s and ’60s) during which most of the factory structures were built. It has left an industrial wasteland in its wake, a world of ruins recycled as artistic relics by the Bechers, which ironically redeems them by remembering them. At the same time, their photographs remain a depressing ecological statement, if also a kind of archaeology of the modern experience….

The photos, which in theory are ideologically free also serve as a comment on ideology. An aesthetization of industry. Death camp structures are also the extreme case then of the triumph of death as a German theme. Its decaying structures as well, showing destruction and death as the end result of ambition which in itself is an ideology. Expertise at producing specimens of death which are what factory ruins represent, and this death is not a poetic vision. We can look at the becher buildings as grotesque prostitutes; their use and abuse the necessary sex used to discharge a profound fear of death. Capitalism as a discharge of annihilation anxiety aroused by the passions of commerce, of profit in a kind of dubious pleasure. She is fully depreciated and amortized. Destroy her. It is such a rejection of syrupy universalism, kitsch, representing a relation between decadence and catastrophe with the allegory of the discarded and unsalvagable being emblematic of discarded human beings.

---More soberly, perhaps, and far closer to our own experience now, there is the capitalist's dreamworld of individual interest, or a fluid collective economy of individual wagers, risks, investments, losses and gains brought into commerce through the market-logic of exchange. As discussed above, however, the Bechers’ own practice and the model of sociality it promises is not vested in either of these systems.--- Read More:http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/04spring/stimson_paper.htm

…But the photographs are full of even more conceptual innuendos: they also suggest, with a kind of dry wit, the entropy — stagnation and inertia — to which the German economy, and by implication, German society is susceptible. Centered in the Bechers’ photographs, the old-fashioned, decaying factory structures — the forgotten, “unthinkable” physical residue on the margins of industrial society — are exposed as the secret center of German society. They represent the drag on it — the sinking center of gravity that represents its undertow of anxiety about its future.Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazine/features/kuspit/kuspit5-10-01.asp

ADDENDUM:

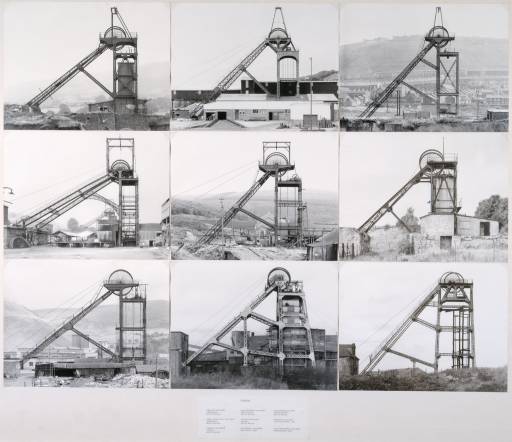

---Bernd and Hilla Becher, Blast Furnaces, 2003. 15 black and white photographs, 68¼ x 94¼in. BHB-795. Courtesy Sonnabend Gallery.--- Read More:http://www.reframingphotography.com/content/bernd-hilla-becher

Factories that no longer work are no longer places in which human beings can work. Thus they no longer make social sense: they are also ironical symbols of post-industrial society — a society in which industrial practice has been pushed to the periphery. Who would have thought that the obsolescence of industrialism itself was built into it by reason of its efficiency?

It is worth noting that the domestic frame structures the Bechers also photograph have been stripped of all signs of human life in the process of being brought to artistic life. They, too, are ghostly ruins. In fact, there are no human beings in the Bechers’ world. It is a ghost town ruled by Death. Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazine/features/kuspit/kuspit5-10-01.asp

Read More:http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/04spring/stimson_paper.

/a>———————————-

Otto Dix. Triumph of Death.---1934.-was ruthless intimidating prose in Dix, haunted by real death and suffering (not Eliot’s stylized and stylish -- not to say forced and fake -- numbness): Dix’s work belongs to the German tradition of the Triumph of Death -- some of his images have a clear affinity with Baldung-Grien’s depiction of it -- while Eliot metaphysicalizes death, as though it was not the brutal, factual, inescapably physical event it is. For Eliot death is an enigmatic idea rather than an everyday reality, a theme worthy of speculative poetry and philosophical discussion, while Dix makes its real effect -- its destructive effect -- on the body explicit. In a sense, Eliot compromises death by thinking about it, as though thinking would soften its blow, but Dix has seen it in action -- experienced it up close and first-hand -- in war. Death cannot be softened by philosophy and poetry: there is no consolation -- conceptual and esthetic consolation prize -- for it. --- Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/otto-dix3-24-10.asp image:http://bentolmanlikesart.blogspot.com/2009/11/otto-dix-german-artist-1891-1969.html

BB: I thought then that what Tinguely was doing was an arts-and-craft interpretation of industry. I didn’t agree with that approach, but today I see it differently. At least I see today that Tinguely brought together a wonderful collection of junk, of things that don’t exist anymore. And I find the early things very good. But I thought that a certain foundry, a certain mine was much more interesting, just for its own sake. In the first place, such structures are monumental and rich in detail. They have an element of the irrational–something that cannot be grasped–but they are nonetheless absolutely functional. They tell the story of the time before World War I, the steel boom. There was a great deal of overproduction; they show that.

UEZ: A piece of history that tells itself?.

BB: A Calvinist baroque. Behind industrial structures is the wish to earn money, sensibly enough. On the other hand, things are produced which are not really needed. The photographs show that….

…UEZ: You are both war children, and parts of your childhood took place during the period of National Socialist rule. To what extent has the issue of war guilt, the political control of industries, concerned you?

BB: We’ve often talked about it, of course. But we’ve taken on industrial sectors in which no specific object was produced; coal and steel can be used to manufacture anything, tanks or tin toys. For me, though, the choice of subject matter was more personal. Right next to my grandparents’ house, in which I grew up, there stood a blast furnace. I could hear it, see it and smell it every day.

UEZ: Can you separate this memory from that of the Third Reich?

BB: I once spoke about that with Jeff Wall, when we were looking at an exhibition of picture books about the Nazi period. He said that there was nothing special about the picture books apart from the flags, which can be seen in almost every shot. Also, there was the permanent artificial euphoria of the marches, all those men in uniform. I certainly saw the suburban houses with steep gables as unpleasant Nazi architecture, even as a child, although I couldn’t put it into context. In Siegen in the `30s, there were also barracks built in this style. But I have always thought that the industrial world is completely divorced from this. It has absolutely nothing to do with ideology. It corresponds more to the pragmatic English way of thinking.

HB: It would be impossible anyway to process something that one viewed entirely negatively. Someone who concerns himself with scorpions must love them to a certain extent. And photography is there precisely to portray what is, not to sort and reproduce only the good and the beautiful. A war photographer doesn’t take his pictures because he loves war. Nonetheless, one has one’s thoughts, and we don’t see industry as a solely positive force. Industry has its crises and excesses, its warmongering characteristics. We have always tried to take a neutral stance in its presentation, and not to engage in glorification.

UEZ: Would it be right then to infer that, with your systematization, you have looked for a standpoint free of ideology?.

HB: Yes, because the work wouldn’t have been possible otherwise. Read More:http://www.americansuburbx.com/2010/03/theory-interview-with-bernd-and-hilla.html

COMMENTS

COMMENTS